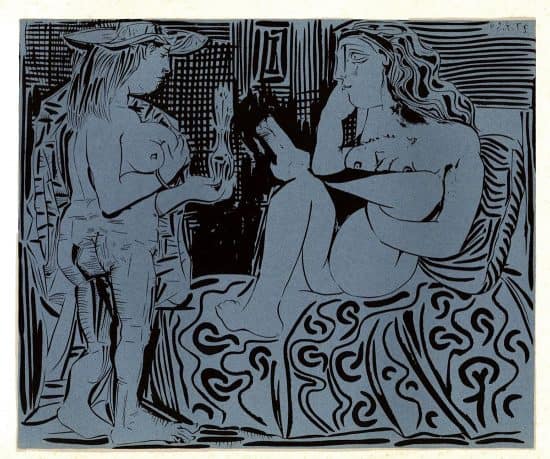

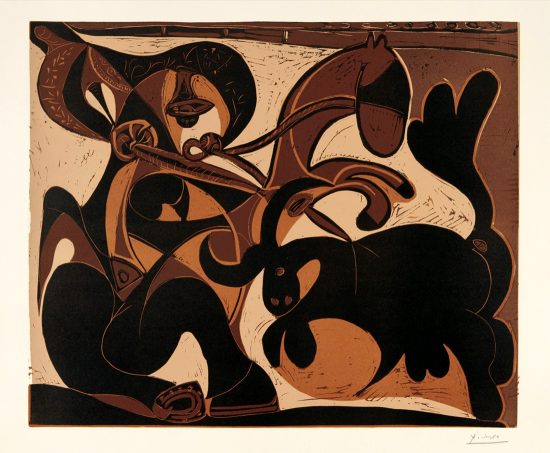

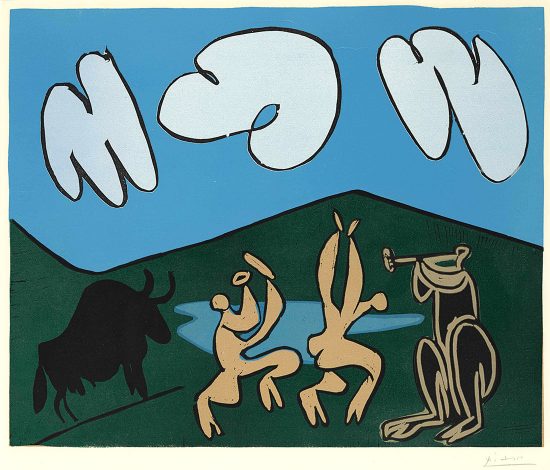

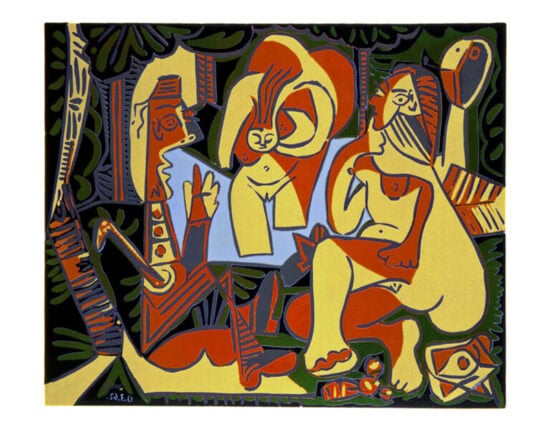

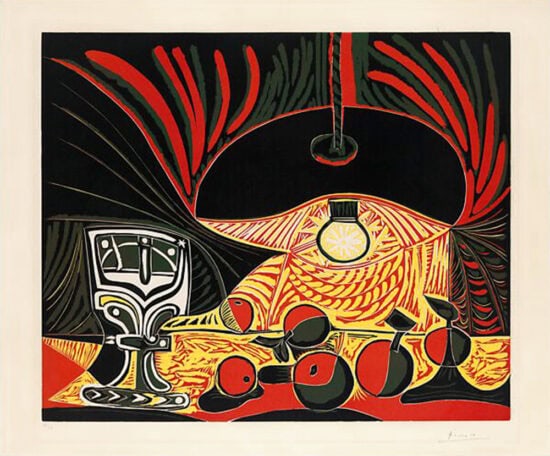

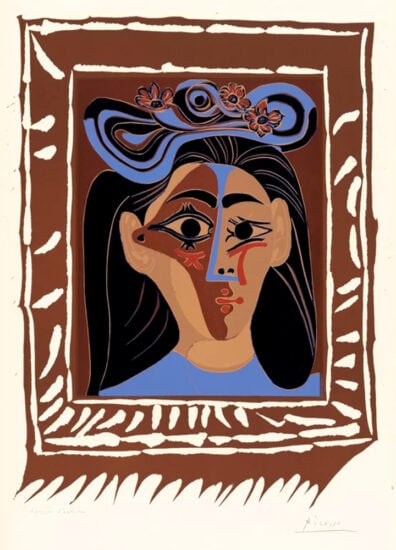

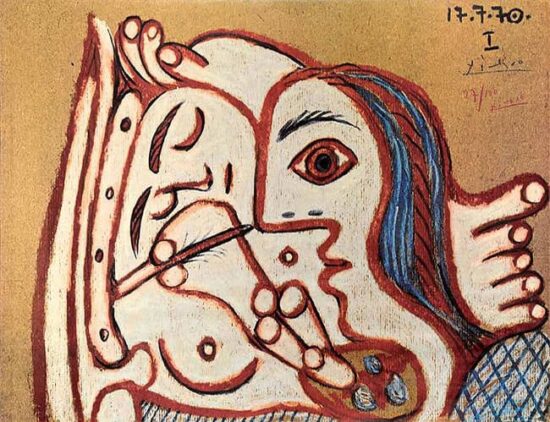

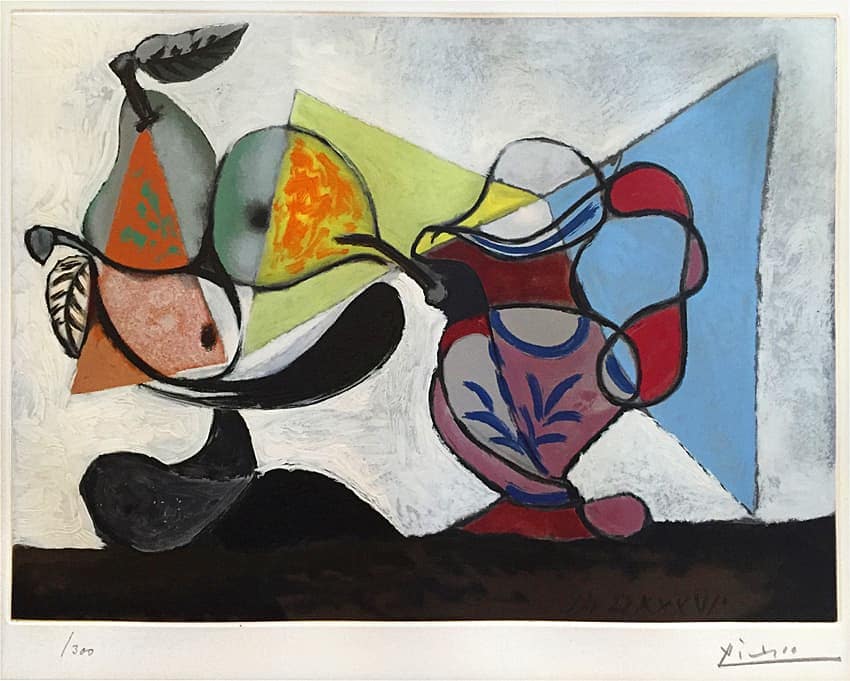

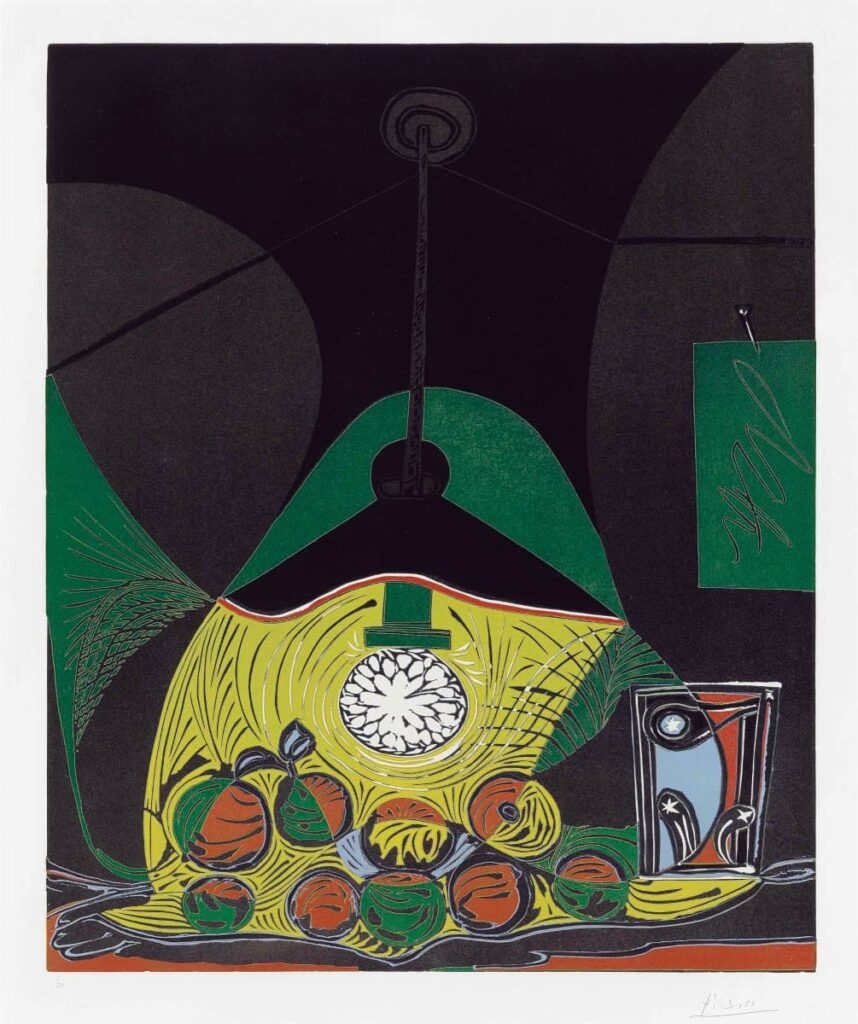

Pablo Picasso’s still lifes occupy a central place in his oeuvre, reflecting both his deep engagement with tradition and his relentless drive for innovation. From his early academic training to his Cubist experiments, the still life offered Picasso a versatile framework in which to explore form, perspective, color, and composition. Ordinary objects—fruit, bottles, musical instruments, and household items—became vehicles for radical artistic inquiry, allowing him to deconstruct reality into planes, facets, and overlapping perspectives. By repeatedly revisiting this subject, Picasso could balance playfulness with intellectual rigor: a simple bowl of fruit could transform into a complex interplay of geometry and shadow, while a guitar might oscillate between tangible object and abstract form. Picasso's still lifes provided an intimate, contemplative space in which Picasso could investigate relationships between objects, textures, and negative space, experimenting with both representational and symbolic possibilities. Through these works, he demonstrated that even the most mundane subject could be elevated to a site of profound aesthetic and conceptual exploration, making the still life not merely a study of objects, but an enduring testament to his ingenuity, vision, and enduring dialogue with the history of art.

Revolutionary Discovery

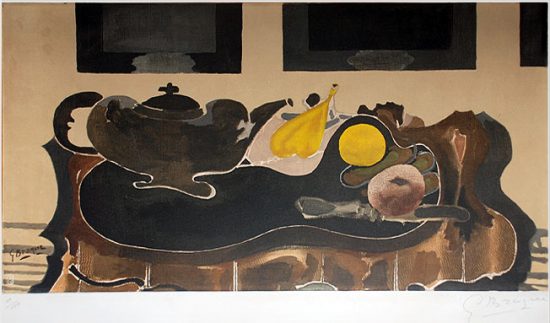

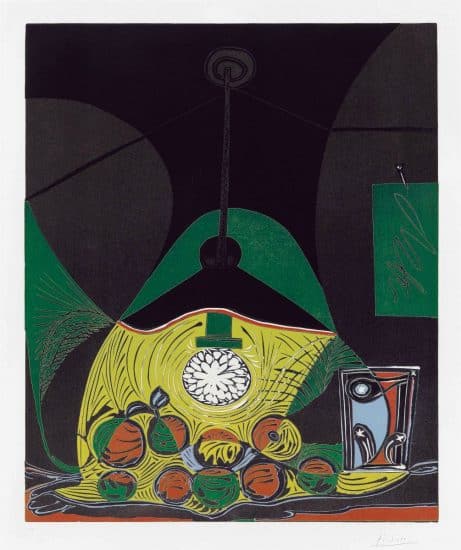

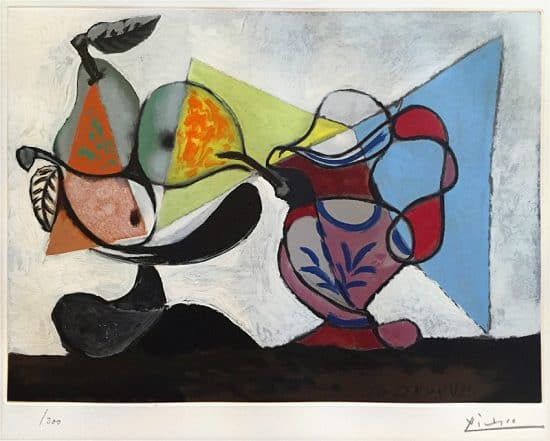

Following Picasso’s revolutionary approach to still life, artists throughout the 20th and 21st centuries reimagined this traditional genre, treating ordinary objects as vehicles for both formal experimentation and conceptual exploration. Picasso’s deconstruction of objects into geometric planes, multiple perspectives, and abstracted forms opened a pathway for contemporaries and successors alike to interrogate the boundaries between representation and perception. Georges Braque, his Cubist collaborator, continued to dissect tablescapes and musical instruments, creating compositions that balanced structure and dynamism, while Juan Gris transformed still lifes into carefully orchestrated harmonies of shape and color, emphasizing precision and compositional clarity. Fernand Léger injected mechanical forms and industrial motifs, reflecting modern life, whereas Giorgio Morandi distilled objects into subtle, meditative arrangements, demonstrating that abstraction and quiet contemplation could coexist. In the latter half of the century, artists like David Hockney reinvigorated still life with bold colors, playful perspectives, and painterly innovation. Meanwhile, Roy Lichtenstein brought the still life into the Pop Art era, translating everyday objects—cups, bottles, vases, and household items—into striking, graphic compositions characterized by comic-book aesthetics, Ben-Day dots, and vibrant primary colors. Across these movements, the still life remained a dynamic arena for artistic inquiry, evolving from Picasso’s Cubist experimentation into a spectrum of modern and contemporary expressions that continually question form, perception, and cultural context.

Picasso Still Lifes in Museums & collections:

1. “Still Life with Chair Caning” (1912) Medium: Oil, oilcloth, and rope on canvas Museum: Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, USA

2. “Glass and Bottle of Suze” (1912) Medium: Oil on canvas Museum: Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, USA

3. “Still Life with Mandolin” (1913–1914) Medium: Oil on canvas Museum: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, USA

4. “Still Life with Skull” (1945) Medium: Oil on canvas Museum: Musée Picasso, Paris, France

5. “Bottle, Glass, and Guitar” (1912–1913) Medium: Oil on canvas Museum: National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., USA

6. “Still Life with Fruit Bowl” (1919) Medium: Oil on canvas Museum: Pushkin Museum, Moscow, Russia

7. “Still Life with Fruit Dish” (1932) Medium: Oil on canvas Museum: Musée National Picasso, Paris, France

Picasso Still Lifes Quick Facts

Q: Why did Picasso paint Still Lifes?

Still lifes allowed him to experiment with form, perspective, and abstraction without the constraints of portraiture, turning ordinary objects into a playground for innovation.

Q: Which Objects as Symbols did Picasso use as Still Lifes:?

Fruit, bottles, guitars, and bowls were not just decorative—they could symbolize life, mortality, music, and domesticity.

Q: What was the Picasso Cubist innovation with Still Lifes?

In collaboration with Georges Braque, Picasso fragmented objects into geometric planes and explored multiple viewpoints in a single composition.

Q: Did Picasso create any mixed media experiments while making Still Lifes artworks?

Works like “Still Life with Chair Caning” (1912) incorporated oilcloth, rope, and newspaper, challenging traditional definitions of painting.

Q: Did any of Picasso Muses Influence his Still Lifes?

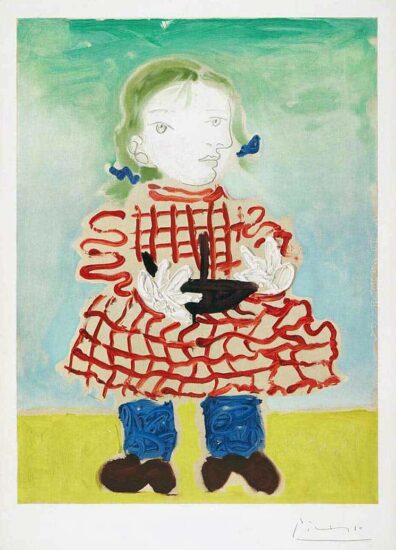

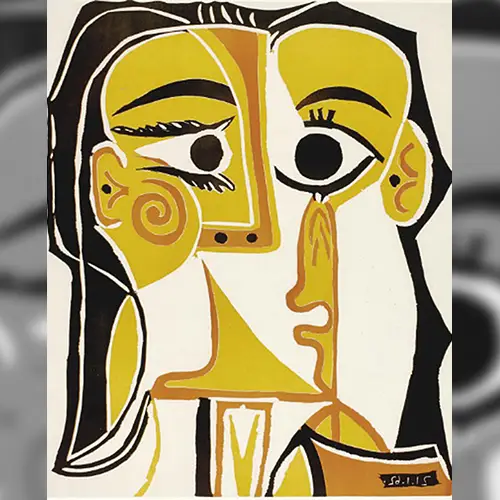

His muses influenced still lifes indirectly. Olga Khokhlova inspired elegance and domestic refinement. Marie-Thérèse Walter brought playfulness and curves into shapes of bowls, vases, and abstracted forms.

Q: Did Picasso Still Lifes include any Humor & play?

Picasso sometimes included quirky or unexpected objects, like newspapers, pipes, or musical instruments, adding playful or ironic undertones.

Q: What are the genre differences between Picasso Still Lifes?

Picasso Blue Period still lifes: somber, melancholic tones.

Picasso Rose Period still lifes: warmer, tender, and lyrical.

Picasso Cubist and later still lifes: bold experimentation with shape, perspective, and abstraction.

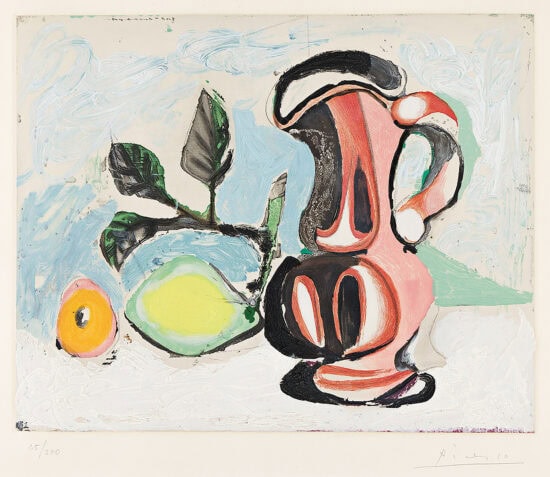

![Georges Braque Lithograph, Nature morte (avec un pichet et citrons) [Still Life with Pitcher and Lemons], c.1950](https://images.masterworksfineart.com/braque2243-550x420.jpg)