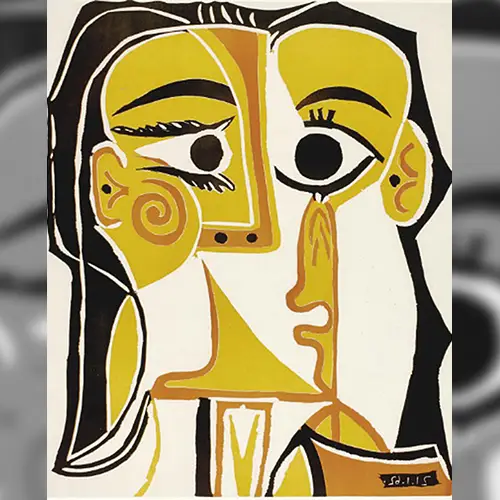

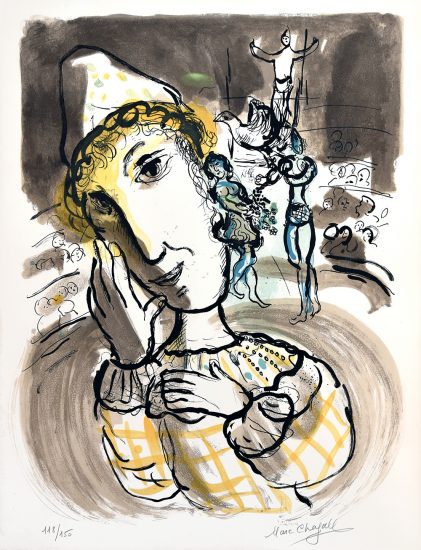

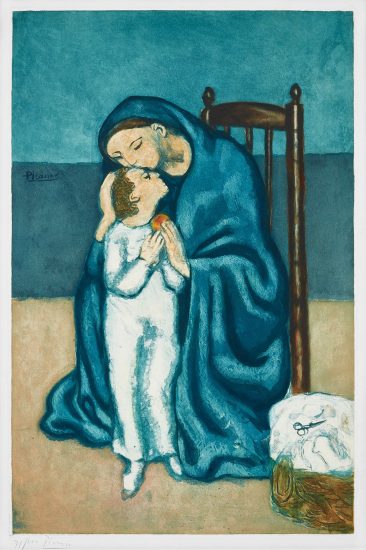

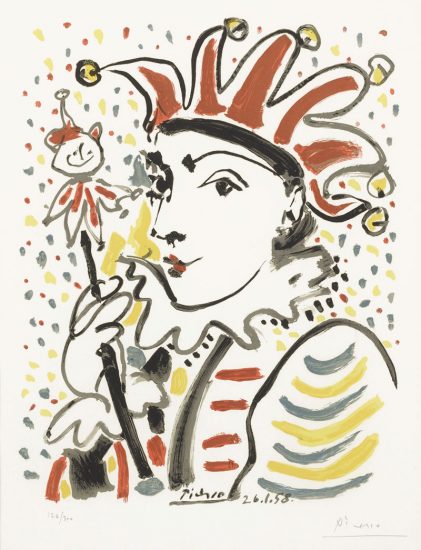

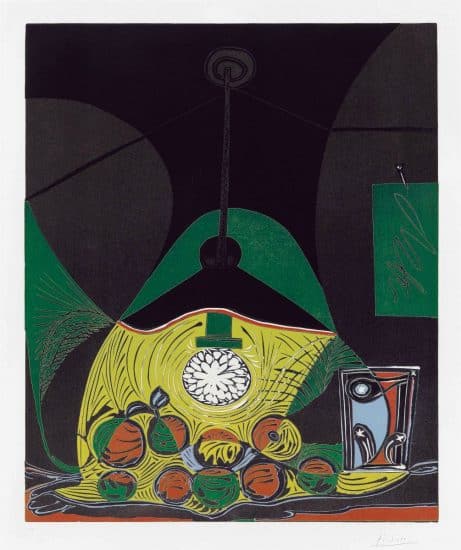

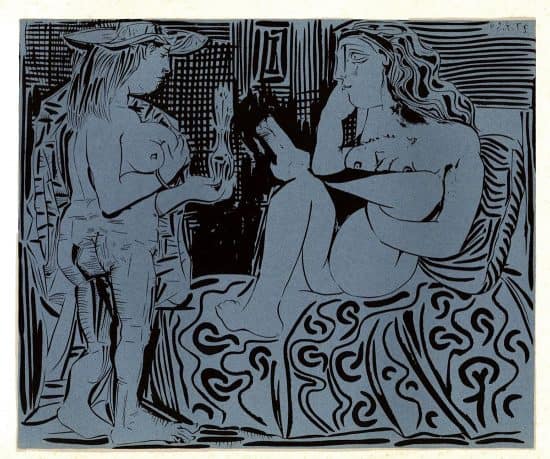

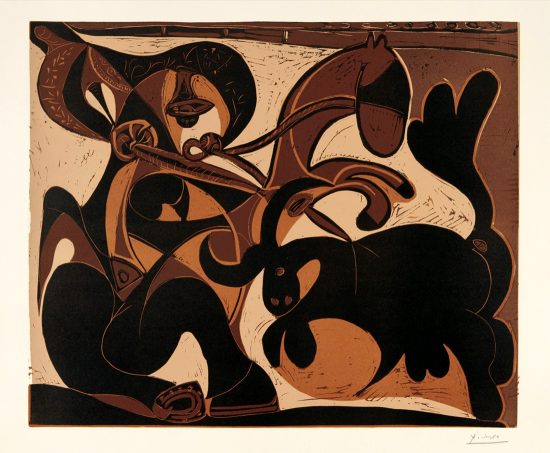

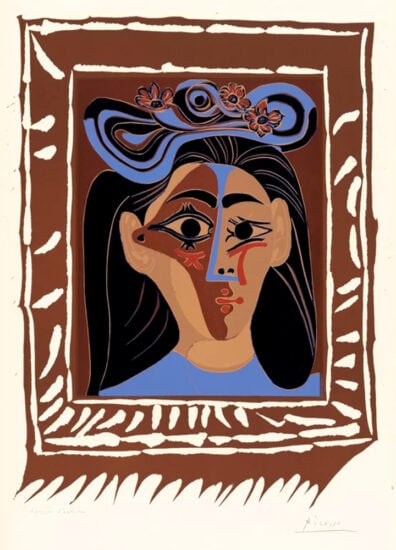

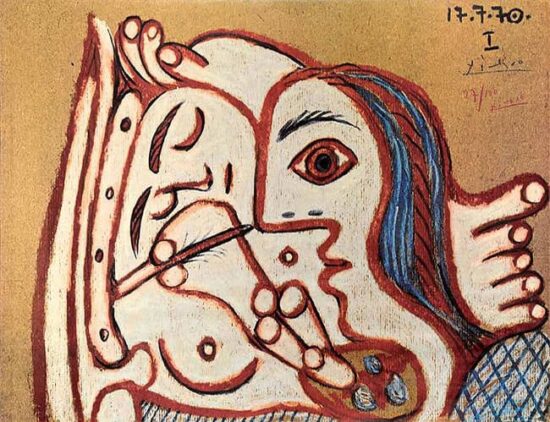

Pablo Picasso’s exploration of the clown as an iconic subject represents a rich intersection of whimsy, melancholy, and profound psychological insight, reflecting both his fascination with performance and his acute observation of the human condition. From the early 20th century onward, clowns, harlequins, and acrobats appeared recurrently in his work, especially during the Rose Period, when the traveling circus and its performers captured his imagination with their colorful costumes, theatrical gestures, and dual nature of joy and sorrow. In these works, Picasso used the clown as a vehicle to probe vulnerability, isolation, and the complexity of identity: the exaggerated masks and painted faces serve as metaphors for the masks we all wear in society, while their expressive postures convey both playfulness and existential poignancy. Across paintings, drawings, prints, and ceramics, the clown became a flexible, recurring motif through which Picasso could experiment with form, color, and composition, blending realism with abstraction and occasionally hinting at the grotesque or the surreal. Ultimately, Picasso’s clowns transcend mere entertainment; they are emblematic of his capacity to fuse emotional resonance with formal innovation, capturing the paradoxical blend of comedy and tragedy inherent in life itself.

What are some famous Picasso Clown artworks?

- “Family of Saltimbanques” (1905) Medium: Oil on canvas Museum: National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., USA

2. “Harlequin with a Glass” (1917) Medium: Oil on canvas Museum: Private collection / periodically exhibited

3. “Acrobat and Young Harlequin” (1905) Medium: Oil on canvas Museum: Pushkin Museum, Moscow, Russia

4. “Seated Harlequin” (1923) Medium: Oil on canvas Museum: Musée Picasso, Paris, France

5. “Clown with a Dog” (1905–1906) Medium: Oil on canvas Museum: Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, USA

6. “Harlequin” (1915) Medium: Oil on canvas Museum: Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, USA

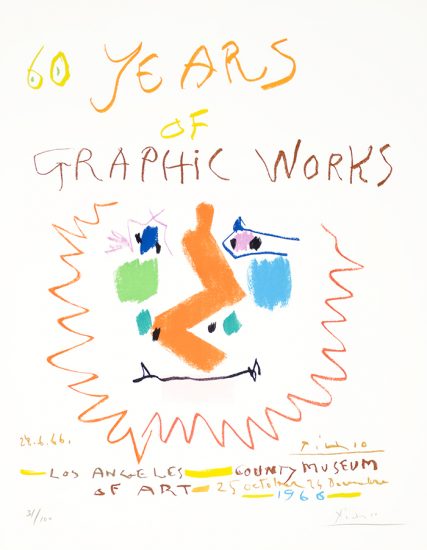

7. “Clown” (Various Drawings and Prints, 1901–1930s) Mediums: Ink, pencil, etching, lithograph Museum: Collections at Musée Picasso, Paris; MoMA, New York; British Museum, London

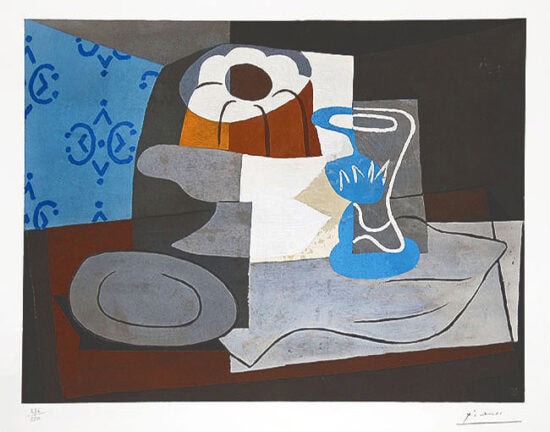

Picasso Clown Drawings

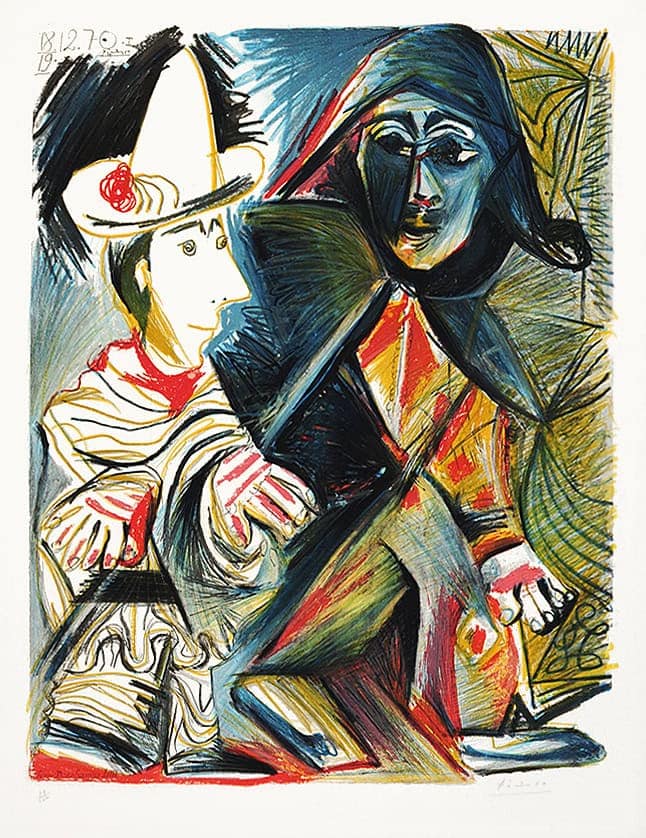

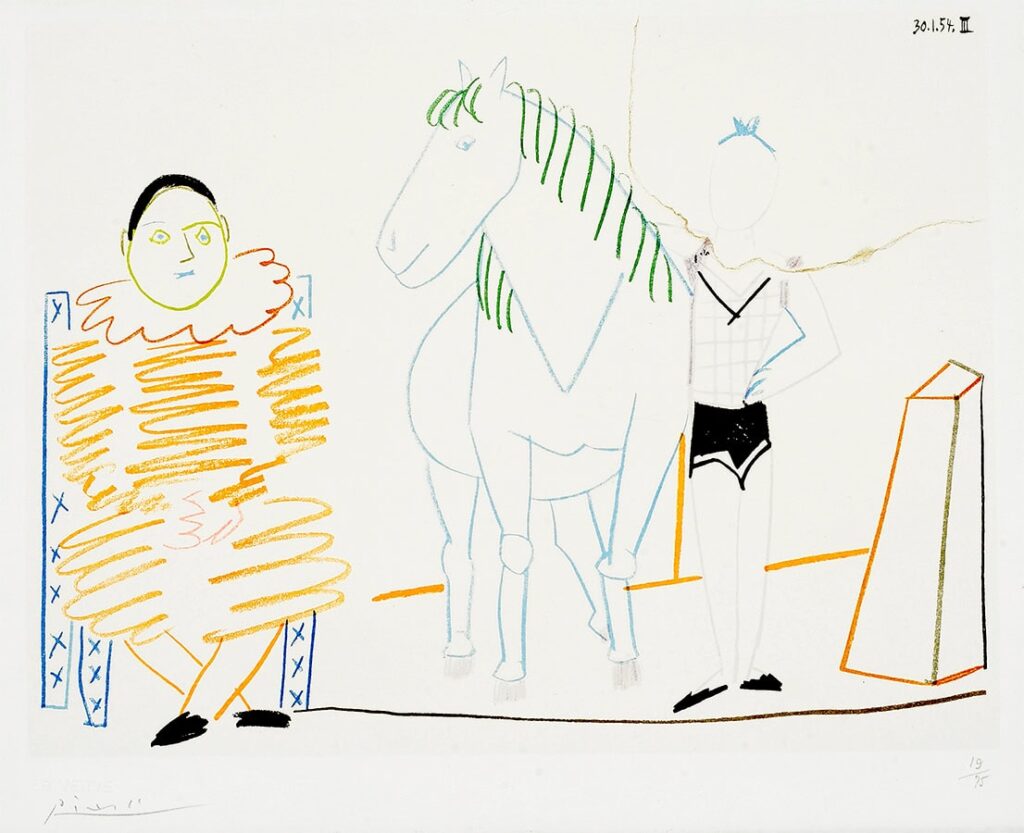

Picasso produced numerous drawings of clowns and harlequins throughout his career, and they represent some of his most intimate and expressive explorations of this iconic subject. These drawings allowed him to distill the essence of performance, emotion, and character into economical lines and fluid gestures, capturing both the theatricality and vulnerability of circus life. Many of the most celebrated works come from his Rose Period (1904–1906), when traveling performers, acrobats, and clowns fascinated him with their colorful costumes and poignant duality of joy and melancholy. Among his most famous clown drawings are “Clown with Dog” (1905–1906), a tender ink-and-pencil depiction highlighting affection and quiet pathos, and “Harlequin Seated” (1905), where the harlequin figure is rendered with rhythmic, expressive lines that convey both elegance and emotional depth. Later, Picasso revisited the motif in Cubist and neoclassical styles, simplifying figures into geometric planes or elongated contours while preserving the psychological and performative essence of the subject. Across pencil, ink, etching, and lithograph, these drawings reveal Picasso’s mastery of line, gesture, and characterization, demonstrating that even in the simplest forms, the clown could embody a spectrum of human emotion—from playful whimsy to existential reflection—solidifying the motif as one of his most enduring and iconic subjects.

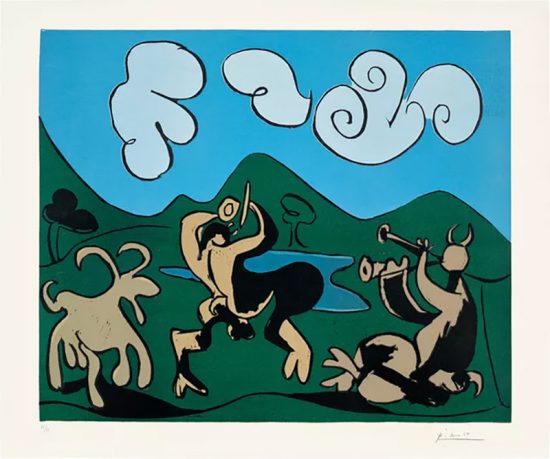

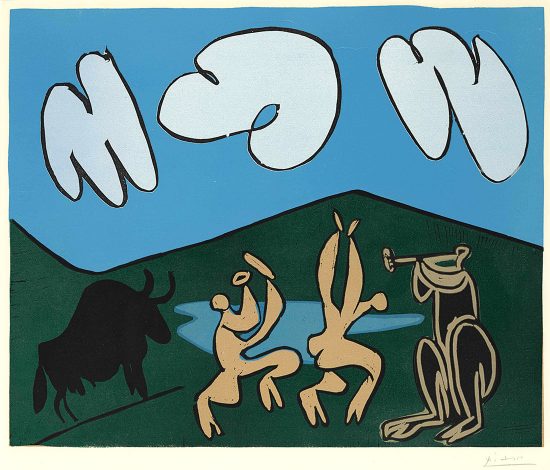

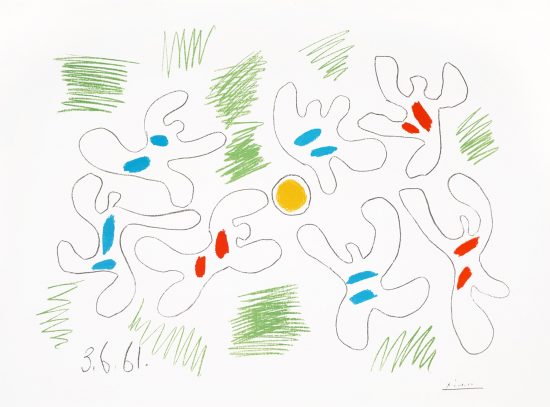

Picasso Clown Lithographs

Pablo Picasso’s lithographs of clowns and harlequins represent a remarkable fusion of technical mastery and emotional expression, allowing him to explore this iconic subject across a more graphic, reproducible medium. Unlike paintings or drawings, lithography gave Picasso the opportunity to experiment with line, contrast, and texture on a scale that emphasized the rhythm and dynamism of his figures. Many of these prints capture the duality inherent in the clown motif—the playful, performative exterior juxtaposed with underlying melancholy or introspection—reflecting both the whimsical and psychologically charged aspects of circus life. Among his most celebrated lithographs are works from the 1930s to 1950s, including “Harlequin with a Glass”, which exemplifies Picasso’s neoclassical clarity and careful composition, and “Seated Harlequin”, where flowing contours and expressive line convey elegance and emotional depth. Other notable prints, such as series of clowns, acrobats, and performers, demonstrate his continuous fascination with movement, theatricality, and the human condition, distilled into economical, powerful lines and subtle tonal shading. These lithographs were often produced in small editions, making them highly sought after by collectors, and today they reside in major collections worldwide, including the Musée Picasso in Paris, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the British Museum in London. Through this medium, Picasso transformed the seemingly simple figure of the clown into a versatile, enduring symbol, blending humor, pathos, and formal innovation in ways that continue to captivate audiences and scholars alike.

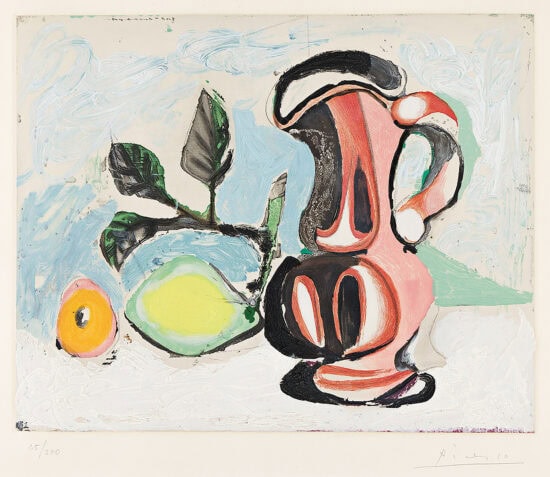

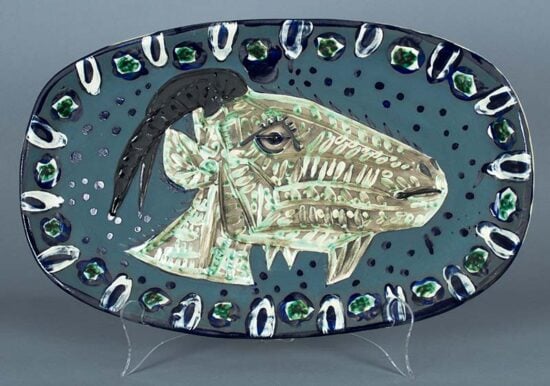

Picasso Clown Ceramics

Picasso’s clowns and harlequins frequently appeared in his ceramics, especially during his Vallauris period (late 1940s–1950s) when he extensively explored pottery and sculptural vessels. He transformed plates, vases, jugs, and bowls into dynamic canvases for these performers, often using playful, exaggerated poses and bold, expressive line work. The curving surfaces of the ceramics allowed him to experiment with movement, perspective, and composition in three dimensions, so that a harlequin or clown figure might wrap around a vase, creating a sense of performance unfolding across the object. These ceramic works often combined humor, theatricality, and artistry, blending everyday function with high art. Notable examples include plates depicting solitary clowns or small groups of acrobats, and vases with harlequin figures integrated into the decorative scheme. Today, these ceramic clowns are housed in major collections such as the Musée Picasso, Paris; Musée National Picasso, Vallauris; and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, highlighting their significance within Picasso’s exploration of iconic subjects across multiple media.

Famous Picasso Ceramic Clowns artworks:

1. “Harlequin Plate” (1952) Medium: Painted ceramic plate Museum: Musée Picasso, Paris, France

2. “Clown Vase” (1951–1953) Medium: Painted ceramic vase Museum: Musée National Picasso, Vallauris, France

3. “Acrobat and Clown Plate” (1954) Medium: Painted ceramic plate Museum: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA

4. “Harlequin and Guitar Vase” (1955) Medium: Painted ceramic vase Museum: Musée Picasso, Paris, France

Picasso Clowns: Quick Q&A & Fun Facts

Q: Why did Picasso paint clowns and harlequins?

They symbolized the duality of human experience—joy and melancholy, playfulness and introspection.

Q: When did Picasso clowns first appear in his works?

During the Rose Period (1904–1906), inspired by traveling circus performers.

Q: Did Picasso only paint clowns?

Picasso also depicted them in drawings, prints (lithographs and etchings), and ceramics, exploring form and emotion across media.

Q: Were they literal portraits?

Rarely; the clowns were often archetypal or symbolic, not specific individuals.

Q: What was Picasso's circus fascination:

He reportedly loved visiting circuses and theaters, sketching performers in motion, capturing gestures, costumes, and theatrical expressions.

Q: Any humorous or quirky facts?

Picasso sometimes painted clowns with pets, musical instruments, or odd props, blending humor with pathos. He integrated curves and movement of ceramic vessels to make clowns appear to perform around the object.

Q: Which Museums hold in their collection Picasso Clown works:

Musée Picasso, Paris

Musée National Picasso, Vallauris

MoMA, New York

Art Institute of Chicago

British Museum, London

Q: Why are clowns iconic for Picasso?

They embody performance, human emotion, and formal experimentation, making them a recurring, enduring motif throughout his career.

Enjoy our collection of Pablo Picasso fine art of clowns.