Picasso’s fascination with goats was as much a reflection of his personal surroundings as it was a testament to his ability to elevate the humble into the iconic. During his years in Vallauris in the late 1940s and early 1950s, goats roamed freely through the sun-warmed courtyards and hillsides of the Mediterranean village, becoming part of his daily landscape. To Picasso, the goat embodied a unique blend of resilience, independence, and earthy vitality—qualities he deeply admired and often mirrored in his own life and art.

In Mediterranean tradition, the goat was also steeped in symbolism: a pastoral creature tied to fertility, rustic abundance, and the ancient rituals of Dionysus, carrying echoes of myth and timeless rural life. Picasso’s depictions of goats—whether in bronze, ceramic, or line drawing—balance affectionate observation with monumental presence, turning a farmyard animal into a sculptural archetype. Unlike the fierce, combative energy of his bulls, the goat’s presence in Picasso’s work is rooted in grounded vitality and playful charm, offering a gentler yet equally potent emblem of life’s enduring force. In his hands, the goat became more than an animal; it became a distilled symbol of nature’s persistence, Picasso’s heritage, and the poetic beauty of the everyday.

Did Picasso have a pet Goat?

Yes, Picasso did in fact have a pet goat, and its presence in his life was as colorful as the artist himself. During his time in Vallauris in the early 1950s, he kept a lively goat named Esmeralda, who roamed freely through his sunlit garden and sometimes even wandered into his studio. Far from being just a charming bit of rural eccentricity, Esmeralda became a living muse, her wiry coat, angular form, and curious temperament capturing Picasso’s imagination.

She inspired not only affectionate sketches and ceramics, but major museum paintings. Esmeralda’s sturdy, unpretentious nature stood in contrast to the high drama of Picasso’s bulls or the ethereal grace of his doves, grounding his animal imagery in a tangible, everyday vitality. For Picasso, she was more than a pet; she was a creature of character and spirit, a reminder of the artist’s deep connection to the rhythms of Mediterranean life and the enduring poetry he found in even the humblest of companions.

Which is Picasso most famous Goat artwork?

The most famous Picasso goat artwork is unquestionably his life-size bronze sculpture She-Goat (La Chèvre), created in 1950 while he was living in Vallauris.

Today, examples of She-Goat are held in major museum collections, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, where it is often cited as one of the great modern sculptures of the 20th century. It stands as both a personal homage—partly inspired by his real-life pet goat, Esmeralda—and a symbolic emblem of fertility, abundance, and resilience, themes that ran through much of his post-war work.

Did Picasso create Ceramics featuring Goats?

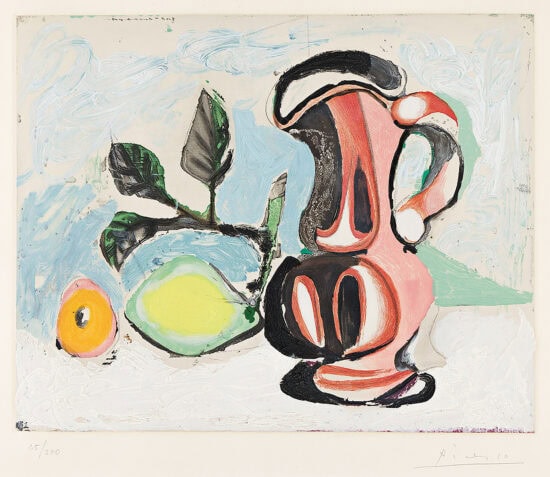

Yes, Picasso created ceramics featuring goats, especially during his prolific years working at the Madoura Pottery Studio in Vallauris in the late 1940s and 1950s.

Goats appear in his ceramic plates, pitchers, vases, and tiles, often rendered in his signature bold, linear style or in playful, almost childlike forms that celebrate the animal’s rustic charm. These works were sometimes purely decorative—painted or incised onto earthenware with sweeping brushstrokes—and other times incorporated into the vessel’s shape, with horns, muzzles, or full goat profiles modeled in relief.

For Picasso, the goat in ceramics echoed the same themes present in his She-Goat sculpture: Mediterranean vitality, pastoral tradition, and the transformation of everyday life into timeless art. The tactile nature of clay, with its earthy connection to the land, was an ideal medium for depicting a creature so rooted in rural life.

These goat ceramics are now highly collectible, with many residing in private collections as well as museums like the Musée National Picasso–Vallauris and the Musée Picasso in Paris.

Picasso Goat Drawings

Among the most notable are:

• Goat (La Chèvre) – A lively ink drawing from 1946–47, where Picasso captures the animal with just a few swift, confident lines, distilling its wiry energy and stubborn personality into pure gesture.

• Studies for She-Goat – A series of sketches made while he was conceptualizing his famous bronze sculpture (1950), exploring the balance of anatomy, volume, and rustic texture.

• Goat and Child – A tender image in which a child stands beside or rides a goat, blending themes of innocence, rural life, and playfulness.

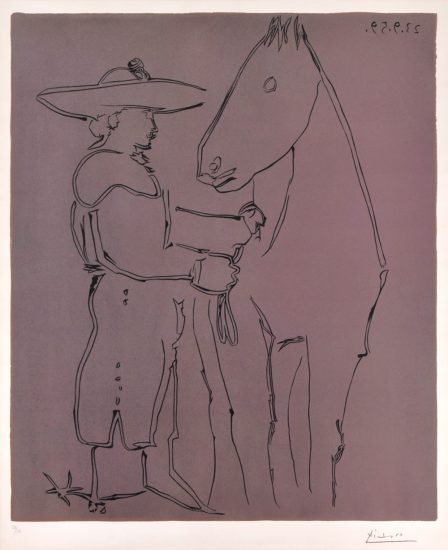

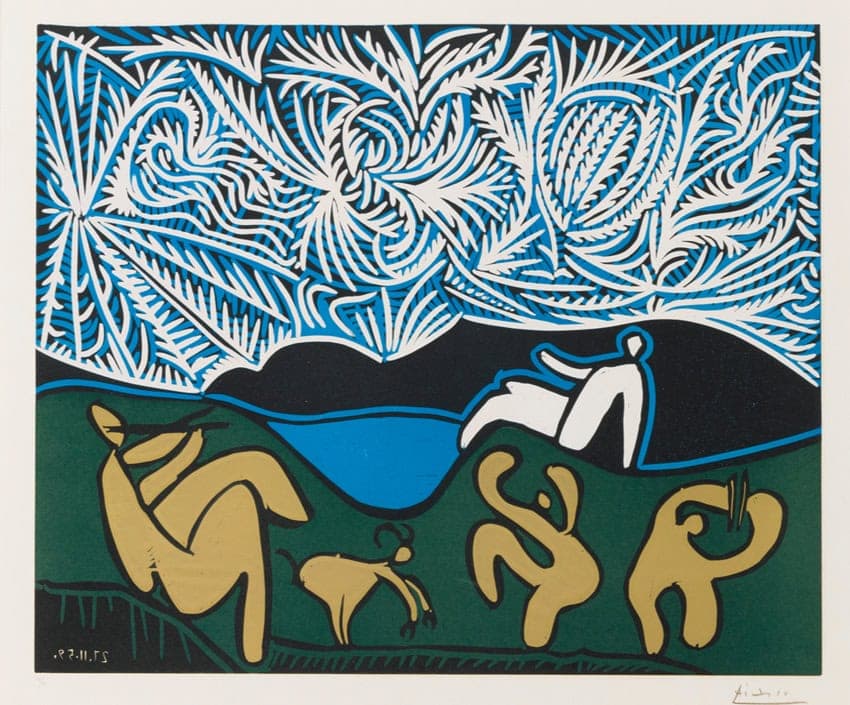

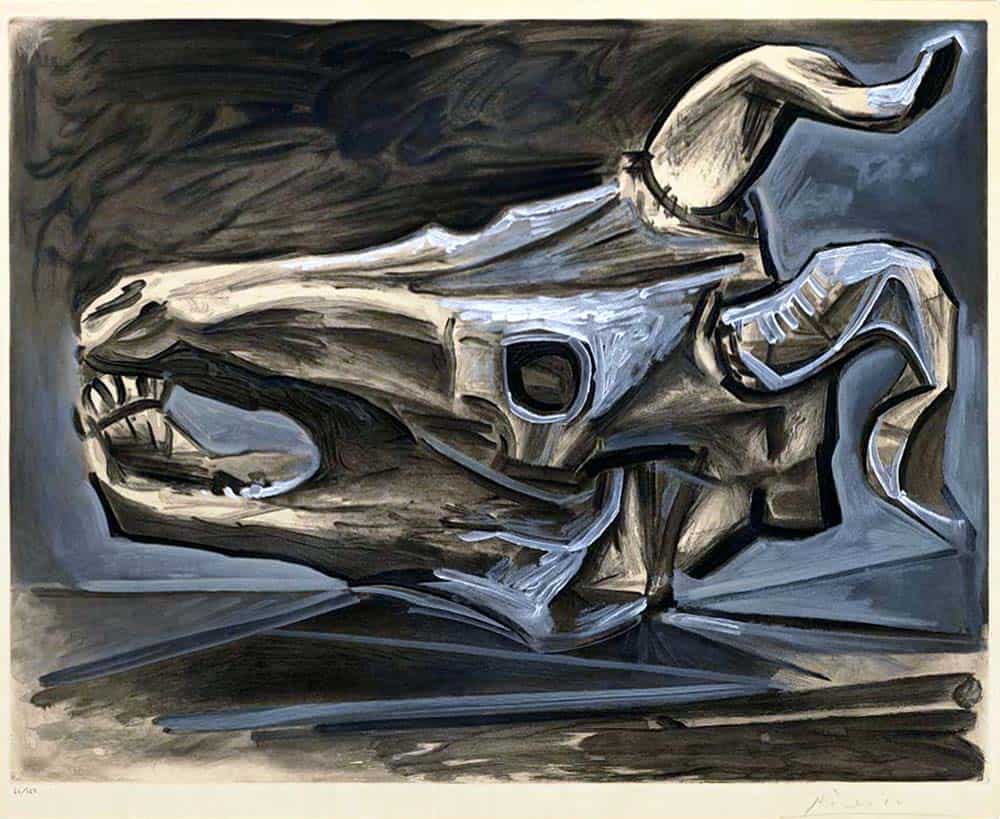

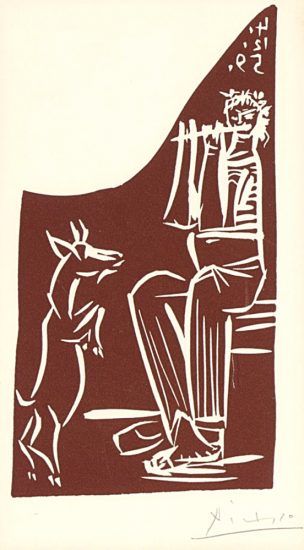

Picasso Goat Linocuts, Lithographs and Etchings

During his time in Vallauris, Picasso also experimented with printmaking to portray goats, often using strong contrasts and simplified forms to highlight their distinctive horns and silhouette.

Picasso created goat lithographs, most notably during the late 1940s and early 1950s when he was immersed in printmaking at the Mourlot Studio in Paris.

One of the most celebrated examples is "The Goat" (La Chèvre), a lithograph that distills the animal into bold, economical lines while preserving its wiry vitality and rustic personality. In these works, Picasso often used a minimal palette—sometimes pure black on white paper—to emphasize form and gesture over detail. The lithographic process allowed him to capture both the quick, spontaneous energy of a sketch and the permanence of a finished artwork, bridging drawing and print.

Some lithographs depict goats alone, standing in profile with their signature arched horns, while others integrate them into more complex pastoral scenes, occasionally paired with children, nudes, or other animals. Goats appear frequently in his Vallauris period prints, embodying Mediterranean life, rural abundance, and a playful yet enduring connection to nature.

Today, Picasso’s goat lithographs are held in major museum collections such as the Musée Picasso, Paris, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. They remain highly sought after by collectors, not just for their rarity, but for the way they encapsulate Picasso’s genius for turning the simplest subject into a timeless modern icon.

Picasso Goat Paintings

Picasso’s goat paintings, while fewer in number than his drawings, sculptures, or ceramics of the subject, are among his most charming and character-filled depictions of animals.

In these paintings, goats are often rendered with the same bold, simplified contours and earthy palette that define much of his postwar work. Sometimes they stand alone in profile, their curved horns and wiry coats outlined in dark brushstrokes; other times they are integrated into sunlit scenes with children, nudes, or other animals, celebrating the harmony between human life and the natural world. The goat here becomes more than livestock—it’s a symbol of vitality, fertility, and Mediterranean tradition.

Picasso approached the goat with varying degrees of abstraction: in some works, its anatomy is loosely sketched in bright, almost playful colors; in others, the form is more solid and sculptural, echoing the rustic monumentality of his She-Goat bronze. A notable example is "Goat and Child" (circa 1950s), where tenderness and humor merge in a sun-washed vision of innocence and rural joy.

While they may not be as famous as his bulls or doves, Picasso’s goat paintings hold a special place in his oeuvre—they are personal, affectionate, and rooted in the everyday beauty of his life in Vallauris.

Picasso & Esmeralda: Q&A & Quirky Tidbits

Q: Who was Esmeralda?

A pet goat owned by Pablo Picasso during his years in Vallauris, France (late 1940s–1950s).

Q: How did Picasso acquire her?

Likely from a local farmer; Vallauris was a rural pottery town, and goats were common.

Q: Why did Picasso keep a goat?

For companionship and the rustic charm it brought to his studio life—plus he genuinely adored animals.

Q: Did Esmeralda inspire Picasso’s art?

Yes—most famously the 1950 She-Goat sculpture, later cast in bronze, now in the Musée Picasso, Paris.

Q: Was she allowed in the studio?

Absolutely. She roamed freely among ceramics, paintings, and sculptures—sometimes dangerously close to wet clay or fresh paint.

Q: Esmeralda Stories from Françoise Gilot?

Françoise Gilot recalled that Esmeralda chewed on flowers, laundry, and even scraps of paper from Picasso’s worktable. Picasso joked she had “the true artist’s appetite for creation—and destruction.”

Q: Was Esmeralda a family pet?

Yes—Picasso’s children Claude and Paloma adored her, often playing with her in the garden.

Q: Why a goat and not another animal?

In Mediterranean culture, goats are symbols of fertility, vitality, and resilience—all qualities Picasso valued.

Q: Did Picasso depict goats in other mediums?

Yes—he painted, drew, made lithographs, and created ceramics featuring goats, often modeled on Esmeralda.

Q: Where can you see Esmeralda today?

While the goat herself is long gone, her likeness lives on in artworks such as our collection in our gallery (Masterworks Fine Art Gallery), museums like Musée Picasso (Paris) and Musée National Picasso–Vallauris.