Pablo Picasso, one of the most influential artists of the 20th century, found endless inspiration in the muses who shaped his extraordinary body of work. Throughout his prolific career, Picasso’s muses were not just passive subjects but active participants in the creative process, fueling his artistic evolution with passion, emotion, and complexity. These women — including Fernande Olivier, Olga Khokhlova, Dora Maar, and Marie-Thérèse Walter — each brought unique energy and symbolism to his art, reflecting different phases of his life and stylistic transformations. Their presence allowed Picasso to explore themes of love, beauty, sorrow, and identity through his groundbreaking experiments in Cubism, Surrealism, and beyond. The dynamic relationship between Picasso and his muses remains a testament to the profound connection between artist and inspiration, making his legacy not only about the art he created but also the deeply human stories behind it. This interplay continues to captivate art lovers, historians, and collectors worldwide, underscoring the timeless allure of Picasso’s masterpieces and the muses who breathed life into them.

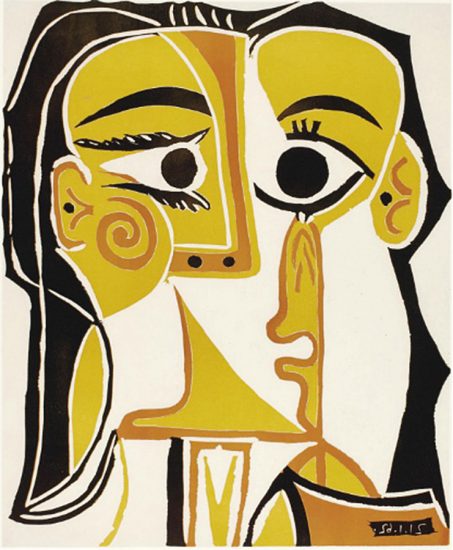

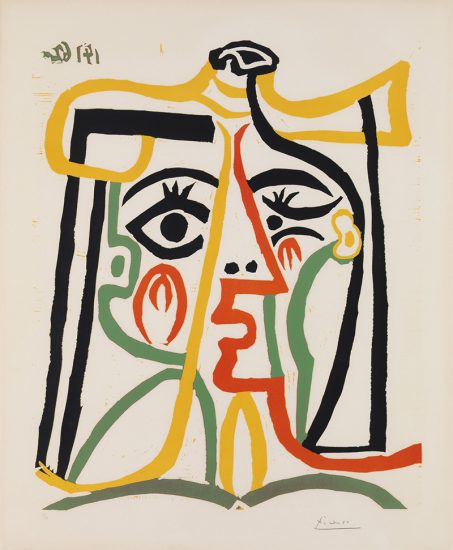

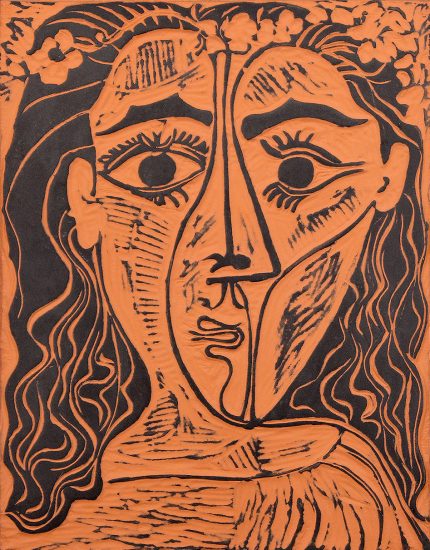

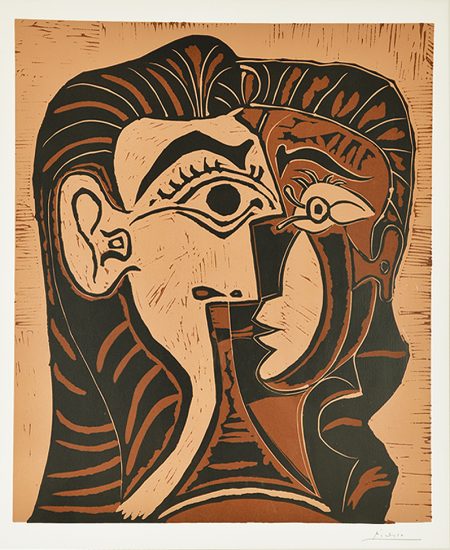

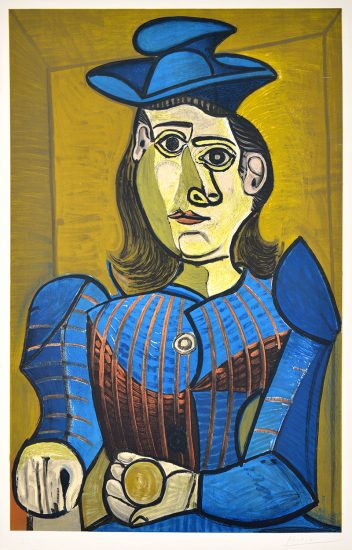

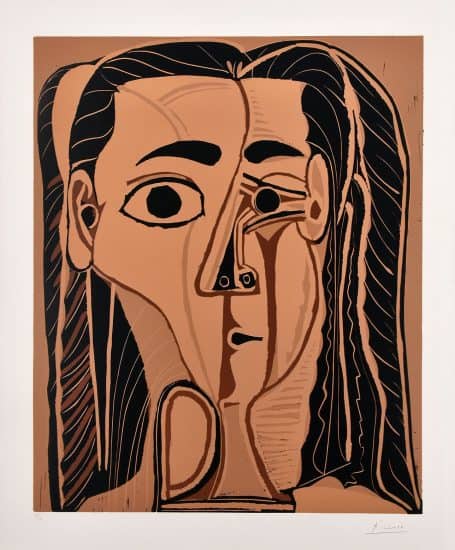

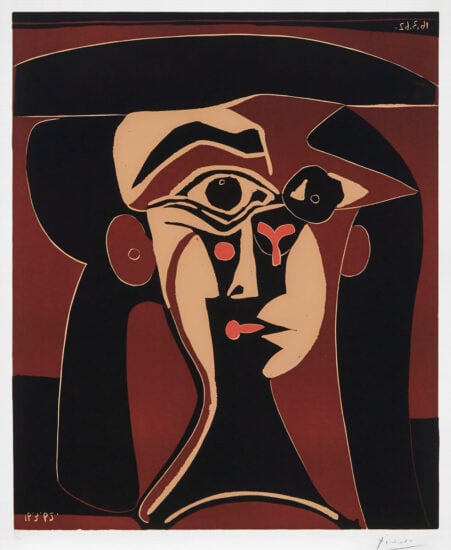

Picasso’s exploration of various artistic mediums played a crucial role in how he portrayed his muses, allowing him to push creative boundaries and express complex emotions. Through Oil painting, Charcoal sketches, sculpture, Madoura Ceramics, Lithographs, Linocuts and Etchings, Picasso brought his muses to life in diverse and compelling ways. Each medium offered unique possibilities—oil paints captured vibrant color and depth, while charcoal emphasized raw emotion and form. His groundbreaking use of collage, incorporating newspapers and fabric, symbolized the fragmented, multifaceted nature of his muses and modern existence. Sculpture and ceramics provided a tactile dimension, enabling Picasso to translate the essence of his muses into three-dimensional forms that echoed their presence and personality. This mastery of multiple mediums not only highlights Picasso’s versatility but also deepens the intimate connection between the artist and his muses. By continuously experimenting with mediums, Picasso reinvented his portrayal of the feminine muse, cementing his legacy as a visionary artist whose works transcend time and continue to inspire.

Below are the stories of these captivating women and the famous works they inspired:

Picasso Muse Fernande Olivier (In Picasso's life from 1904-1912)

The first woman to capture Pablo Picasso’s attention and heart was Fernande Olivier ( Read Loving Picasso: The Private Journal of Fernande Olivier*). By 1904, he had settled permanently in Paris, taking a studio in a rundown building on the Seine. It was here that Fernande Olivier caught his eye, a beautiful artists’ model with striking red hair, almond eyes and a voluptuous figure. Although Fernande was technically married, she stayed with Picasso for nine years.

A fiercely independent woman who kept her own affairs, she is responsible for ending his Blue Period and beginning his Rose Period, in which he abandoned the somber tonalities and the melancholy of his Blue Period in favor of a lighter palette and idealized forms. Such famous works featuring her include Head of Woman (1909), Lady with a Fan (1905) and Portrait of Fernande Olivier (1909).

Facts about Picasso’s Muse Fernande Olivier

Fernande played pivotal and fascinating role in Picasso’s life, especially during his early Paris years. Known as the The Bohemian Firecracker. Lover and Muse from 1904-1912

- They Lived in a Crumbling Artist Commune: Le Bateau-Lavoir. In 1904, Picasso moved into the Bateau-Lavoir, a rundown building in Montmartre that became home to bohemian artists and poets. He met Fernande Olivier there, who was a model, actress, and free spirit. Their shared apartment had no running water or heat — but was filled with paint, poetry, wine, and drama.

Fernande later said: “We were cold, hungry, and madly in love.”

2. Fernande Was the First Woman Picasso Lived With. She was his first long-term partner, and their relationship marked the start of Picasso’s Blue Period shifting into his Rose Period.

Picasso was deeply possessive, but Fernande was independent — the combination was volatile.

3. She Wasn't Her Real Name. She was born Amélie Lang, but took the name Fernande Olivier as a pseudonym when she fled an unhappy marriage. She kept her married status a secret from Picasso for years — which outraged him when he found out.

4. She Inspired Some of Picasso’s Most Romantic Early Work. During their time together, Picasso moved away from the melancholy of the Blue Period and began painting more vibrant, sensuous works:

- La Femme en chemise (1905)

- La Toilette (1906)

- Woman with Loaves (1906)

She was the model for many of his circus-themed Rose Period works, featuring harlequins, acrobats, and performers — often metaphors for their own lives

5. Picasso Took Her to Gósol, a Remote Spanish Village. In 1906, they escaped to Gósol, in the Catalan Pyrenees, for a summer retreat. There, Picasso's style began transitioning toward primitivism, laying the groundwork for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

Picasso: “Everything changed when I met Fernande, and again when I left Gósol.”

6. Their Relationship Was Extremely Volatile. Picasso could be moody and domineering. Fernande, bold and outspoken, often fought back. There were jealous rages, violent arguments, and long silences, especially as Picasso's fame grew.

One night, Picasso reportedly locked Fernande in their room because she was flirting with another man at a café.

7. She Wrote a Memoir — and Picasso Tried to Suppress It. In the 1930s, Fernande published “Picasso and His Friends”, a memoir about her life with him and the Montmartre circle. Picasso was furious — he tried (unsuccessfully) to prevent its publication, feeling it betrayed his privacy.

Despite this, the book is now considered an important source on early 20th-century Parisian art life.

8. They Were the Original Boho Power Couple. Before Picasso's later famous lovers like Dora Maar and Françoise Gilot, Fernande was his first true muse — the original partner of his starving artist phase.

Together they lived the full Parisian bohemian dream: art, absinthe, arguments, and wild Montmartre nights.

As he became more successful, Picasso became more paranoid, and soon he developed an intense possessiveness with Fernande, even going so far as locking her in a room when he would leave. She finally left him in 1912 for an Italian painter, and impoverished took various odd jobs to survive. In 1933 she published her memoir, Picasso and His Friends, outraging Picasso and in 1956, deaf and arthritic, persuaded Picasso to pay her a small pension in exchange for her promise not to publish anything further about their relationship.

Picasso Muse Eva Gouel (Marcelle Humbert) (In Picasso's life from 1912-1915)

In retaliation for Fernande leaving him, Pablo Picasso took up with one of her friends, Marcelle Humbert, a frail, slender young woman whom was known as Eva. Eva is considered the “queen of his cubist works” as she is portrayed broken up and reassembled in an abstracted form through works such as Nude, I Love Eva(1912), Femme assise dans un fauteuil (1913) and Woman in an Armchair (1913-1914).

When Eva contracted tuberculosis in 1915, he cared for her but was secretly sleeping with a young woman named Gaby, depicting her in a series of intimate paintings and sketches. Eva succumbed to her sickness, and Picasso was devastated, professing his love to Eva by painting “I Love Eva” in some of his paintings.

Facts about Picasso's Muse Eva Gouel (Marcelle Humbert)

She was a lesser-known but deeply significant muse and love in Picasso’s life.

- Her Nickname Was “Ma Jolie” — and It’s Hidden in His Paintings. Picasso affectionately called Eva “Ma Jolie” (“My Pretty One”), and he immortalized her in several Cubist paintings, notably:

Ma Jolie (1911–12) — a visually complex painting where her name is literally written into the composition.

You can find the words “Ma Jolie” stenciled across the abstract forms — like a coded love letter.

2. Their Relationship Started in Secret. At the time he met Eva, Picasso was still living with Fernande Olivier. He began secretly seeing Eva around 1911, and the relationship slowly replaced Fernande without public scandal — a rare case of discretion for Picasso.

3. Eva Was Not a Model — But He Painted Her Anyway. Unlike Fernande or later muses, Eva wasn’t a professional model. She worked behind the scenes in the fashion world, possibly as a costumer for a theater.

Yet she inspired some of Picasso’s most emotionally charged Cubist works — even though her physical likeness is rarely recognizable.

4. She Died Young — and He Was Devastated. Eva died in 1915, likely from tuberculosis or cancer, at just 30 years old.

Picasso was so devastated, he reportedly stopped painting for weeks, rare for someone who lived and breathed art. He wrote in a letter: “My poor Eva is dead.”

5. He Never Spoke Much of Her Again — But Never Forgot Her. After Eva's death, Picasso almost never discussed her publicly.

Some historians believe her loss left a quiet emotional scar, visible in the darker tones and abstraction of his mid-1910s work.

- She Helped Usher In the Cubist Revolution

While Picasso and Georges Braque were developing Cubism, Eva was his emotional anchor during this radical shift. She didn’t pose for Cubist portraits — she became the emotion behind them.

6. We Know Her Story Thanks to Letters and Friends

Because Eva died young and left behind little writing, we know her mostly through:

Picasso’s letters

Memoirs of friends

Subtle references in his work

She remains one of the most mysterious and underrated women in Picasso’s romantic life.

Picasso Muse Olga Khokhlova (In Picasso's life from 1917-1927)

After Eva’s death in 1915, he left France for Rome to paint the scenery for a ballet and soon fell in love with one of the ballerinas, a Russian named Olga Khokhlova. Refusing to succumb to his advances, Pablo Picasso became completely obsessed with having her and, after Olga gave in, they were married in 1918, making her his first wife.

Olga detested Picasso’s unflattering cubism style and demanded to only be portrayed in a more flattering academic manner. This turned Picasso’s portrayals of her to a more naturalistic style as she embodied the ideals of Picasso’s Neoclassical period, which were characterized by a renewed interest in naturalistic representations of the human form. Such works are Portrait of Olga in an Armchair (1918), Olga in a Mantilla (1917), Madame Olga Picasso (1923) and Portrait of Olga Khokhlova (1923).

Olga’s signs of madness however were brought on by Picasso’s constant infidelities, which had driven her to the verge of a nervous breakdown. Unable to bear her husband’s infidelities any more, Olga took their son and left the artist to live in the South of France where she remained separated, but obsessed with Picasso for the rest of her life. Picasso refused to grant her a divorce as he did not want her to receive half of his wealth, and she refused to completely let him go, wanting to make his life as miserable as possible until her death in 1955. Picasso would immortalize their battle in works such as The Minotaurmachy (1935) and Bullfight: Death of the Torero (1935). Setting up a home in Paris, they had a son named Paulo Picasso who was the inspiration for a series of tender works titled Maternité. The marriage was happy at first, but then life became very demanding. Picasso lost interest and their marriage fell apart, with Picasso’s style becoming aggressive using colors that expressed his anxiety over Olga who was showing signs of madness.

Facts about Picasso's Muse Olga Khokhlova

Picasso’s relationship with Olga Khokhlova, his first wife, is full of striking contrasts: elegance and conflict, glamour and control, devotion and eventual disillusionment.

- She Was a Russian Ballet Dancer. Olga was a Ukrainian-born ballerina with Sergei Diaghilev’s legendary Ballets Russes. Picasso met her in 1917 while designing the set and costumes for the ballet Parade in Rome.

She didn’t like him at first! She thought he was “scruffy and strange.”

- She Was Picasso’s First (and Only Legal) Wife. They married in 1918 in a Russian Orthodox Church in Paris. Olga was his only legal wife, and the marriage brought Picasso into upper-class society — tea parties, chauffeurs, and tailored suits.

Their wedding was attended by Jean Cocteau and Max Jacob, among others.

- She Changed His Art Style — Temporarily. During their early marriage, Picasso shifted to a more neoclassical style, painting elegant, serene portraits of Olga.

Notable works:

- Olga in an Armchair (1918)

- Portrait of Olga with a Fan (1923)

This was a massive departure from his wild Cubism — all soft lines, poised hands, and refined beauty.

- Their Son Paulo Was a Muse Too. Olga gave birth to Paulo Picasso in 1921. Picasso loved painting Paulo as a baby — dressed as a harlequin, a jockey, or playing with toys.

Later, Picasso called Paulo a “spoiled brat” and the two had a strained relationship.

- Olga Loved Glamour — Picasso, Not So Much. She adored high society, fashion, and luxury — while Picasso remained a creature of bohemian habits. Their worlds clashed: she wanted soirées, he wanted solitude (and, eventually, other women).

Picasso joked that marriage to Olga felt like being “trapped in a silk prison.”

- Things Got Very Ugly. By the late 1920s, Picasso began a secret affair with 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter. When Olga found out in 1935 — and learned Marie-Thérèse was pregnant — she left Picasso immediately but refused to divorce him.

Why? Under French law at the time, divorce meant division of assets — and Olga wanted to keep her claim to his estate intact.

They remained legally married until Olga’s death in 1955 — though they never lived together again.

- Her Image Became Distorted in His Art. As their marriage soured, Picasso’s depictions of Olga shifted: From elegant and graceful → to twisted, sad, and haunted.

In some later works, he portrayed her as bitter and monstrous, reflecting his own resentment.

- She Never Stopped Loving Him. Despite the betrayal and separation, Olga continued to identify herself as “Madame Picasso” until her death.

She was fiercely protective of her son’s inheritance and remained emotionally connected to Picasso — even though they never reconciled.

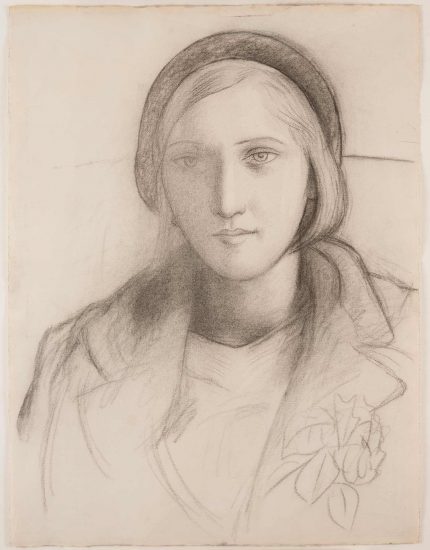

Picasso Muse Marie-Thérèse Walter (In Picasso's life from 1927-1936)

It was during the dissolution of his marriage with Olga, that in 1927 Pablo Picasso met a beautiful blonde, Marie-Thérèse Walter, on a Parisian street. Soon they became lovers, and although Marie-Thérèse was just 17, and Picasso was 46, she was the most enduring love of his life, perhaps the only woman who made him truly happy.

Intelligent but not intellectual, Marie-Thérèse was submissive and tolerant. With her full-bodied frame and submissive nature, Picasso easily manipulated her to suit his pictorial and sculptural sensibilities, which made her an ideal muse and model for his Surrealist period, in which he explored extreme physical and psychological states, often by rendering the human figure with imaginary and distorted forms.

Picasso’s paintings of her, while highly sensual, are suffused with a tenderness that is absent from his paintings of other women. It was Marie-Thérèse who was the inspiration for many of Picasso’s famous Vollard Suite etchings, as well as Sleeping Nude (1932), Marie-Thérèse Walter in Le Rêve (The Dream) (1932), Marie-Thérèse avec une guirlande (1937) and The Farmer’s Wife (1938).

In 1935, Marie-Thérèse gave birth to Picasso’s first daughter, Maya. Although Picasso was delighted, his dalliances with other women became too much for their relationship. Leaving him in 1936 after losing his affections to Dora Maar, Marie-Thérèse lived a quite life. She remained loyal to Picasso even after their affair ended, and even though she declined his proposal of marriage following the death of his wife Olga in 1955, she eventually hung herself in 1977, four years after Picasso died. It is a statue of Marie Thérèse that was placed over his grave when Picasso died, symbolizing his eternal love for her.

Facts about Picasso's Muse Marie-Thérèse Walter

From their secret beginnings to their tragic end. Their relationship was marked by passion, secrecy, artistic devotion, and eventual heartbreak.

- Relationship Began in Secret. Picasso met Marie-Thérèse in 1927, when she was just 17 and he was 45, still legally married to Olga Khokhlova. He approached her outside Galeries Lafayette in Paris and struck up a conversation that led to a years-long affair.

For several years, their relationship was completely hidden, especially from Olga.

2. They Lived Just Blocks Apart — Secretly. Picasso rented Marie-Thérèse an apartment close to the family home he shared with Olga, in Paris.

He would sneak away to paint her, sculpt her, and spend time together, while maintaining the appearance of a faithful husband.

3. She Inspired an Entire Period of His Work. Marie-Thérèse became Picasso’s muse of the early 1930s. Her presence coincided with his shift toward more voluptuous, curvaceous, and emotionally charged art.

She was the subject of some of his most iconic works:

- Le Rêve (1932)

- Nude, Green Leaves and Bust (1932)

- Girl Before a Mirror (1932)

Her features — round face, Grecian nose, athletic form — were stylized into dreamy, sensual forms that dominated his work during this time.

4. They Spent Time at Château de Boisgeloup. In the early 1930s, Picasso bought a country estate, Château de Boisgeloup, where he could be with Marie-Thérèse more freely. There, she modeled for him in privacy, and he created several major sculptures and paintings.

It was their quiet escape, away from the complexities of city life and his marriage.

5. She Became the Mother of His Child. In 1935, Marie-Thérèse gave birth to Maya Widmaier-Picasso, Picasso’s daughter. This was the breaking point with Olga, who immediately separated from Picasso, though they remained legally married.

Marie-Thérèse and Maya lived quietly on the fringes of Picasso’s life, never fully integrated into his public world.

6. They Never Lived Publicly as a Couple. Despite the intense passion, Picasso never truly shared a public domestic life with Marie-Thérèse. After Maya’s birth, he moved emotionally toward Dora Maar, and later Françoise Gilot.

Marie-Thérèse and Maya were often kept separate from his artistic and social circles — though he continued to support them financially.

7. She Was Involved in a Famous Love Triangle. In the late 1930s, Picasso was romantically involved with both Marie-Thérèse and Dora Maar.

A now-legendary moment occurred when both women confronted each other in his studio — and reportedly fought, while Picasso watched in fascination.

Picasso later quipped: “They fought. That’s how it should be. Women must fight for a man.”

(Not his finest moment)

8. Her Image Endured Long After the Romance Faded. Even after Picasso moved on to other partners, he never stopped painting her. Marie-Thérèse's likeness appeared in his work as a symbol of lost youth, sensuality, and memory.

In many ways, she became a mythic figure in his visual language — eternal and luminous.

9. She Never Fully Moved On from Him. Although she had her own life and relationships after Picasso, Marie-Thérèse remained emotionally tethered to him.

She preserved letters, drawings, and memories — and never publicly resented him.

10. She Died by Suicide After His Death

Picasso died in 1973. Just four years later, in 1977, Marie-Thérèse died by suicide at age 68.

Some close to her believed she never overcame the emotional weight of their complicated relationship and his absence.

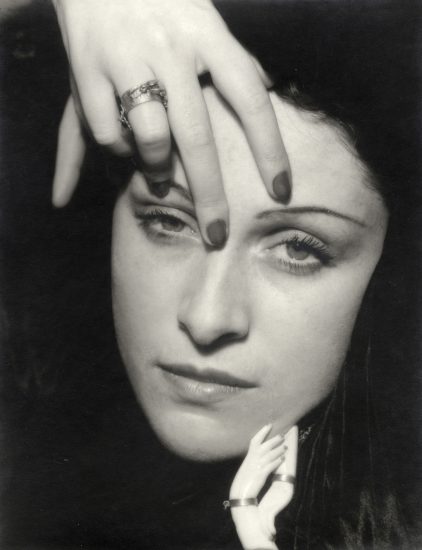

Picasso Muse Dora Maar (In Picasso's life from 1936-1944)

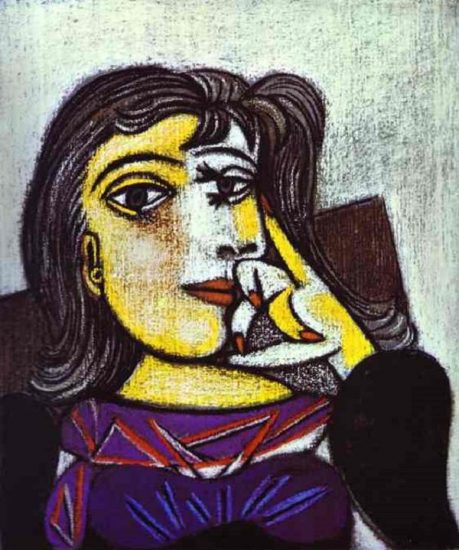

At 29 years old Dora Maar was nearly half Pablo Picasso’s age, but she was intellectual, gifted and beautiful, and there was an instant connection as she was a photographer, painter and poet who would become Picasso’s lover for seven years. She witnessed the step-by-step creation of the Guernica (1937), Picasso’s greatest masterpiece, and her features are scattered throughout the brilliant work that depicts the tragedies of war and the suffering such chaos brings on innocent civilians.

Picasso’s works of her are portrayed with acidic colors and angular forms as can be seen in the Portrait of Dora Maar (1937), Weeping Woman (1937), Dora Maar au Chat (1941), Buste de femme au chapeau a fleurs (1942) and Femme assise (Dora Maar) (1944). As Picasso himself noted: “For me she’s the weeping woman. For years I’ve painted her in tortured forms, not through sadism and not with pleasure, either; just obeying a vision that forced itself on me. It was the deep reality, not the superficial one.”

Dora suffered frequent emotional distress and upon learning about his newest affair with Françoise Gilot in 1945 suffered a total mental collapse. It was during this time that Picasso left her for Françoise, and Maar after undergoing psychoanalysis, went back to painting in Paris. In later years she became a recluse, dying poor and alone. It was Dora who once famously told Picasso: ‘As an artist you may be extraordinary, but morally speaking you are worthless.’

Facts about Picasso's Muse Dora Maar

Picasso’s relationship with Dora Maar was one of his most intense, complex, and creatively charged. It was marked by deep intellectual connection, emotional turbulence, and powerful artistic influence on both sides.

- She Was an Acclaimed Photographer and Surrealist. Dora Maar (born Henriette Theodora Markovitch) was already an established artist and photographer when she met Picasso in 1936. She was close to André Breton and the Surrealists, known for her haunting, dreamlike photos. Her intelligence and creative talent deeply impressed Picasso, who was used to more passive muses.

She documented the making of Guernica — the only person allowed to photograph the process.

2. Their First Meeting Involved a Knife Game. They met at the café Les Deux Magots in Paris. Dora sat alone, stabbing a knife between her gloved fingers into the table — a risky game. When she nicked herself, Picasso asked for the bloody gloves and kept them.

He reportedly said: “That’s how I knew she was mine.”

3. She Was His “Weeping Woman”. Dora became the embodiment of emotional anguish in Picasso’s work — especially during the Spanish Civil War. He often painted her crying, distorted, and fractured, famously in:

- The Weeping Woman (1937)

- Portrait of Dora Maar (1937)

- Woman with a Handkerchief (1938)

He once said: “For me she’s the weeping woman... It’s not a painting of her crying. It’s Dora herself.”

4. She Challenged Him Creatively. Dora wasn’t a passive subject — she was a creator, not just a muse. They debated philosophy, politics, and art. She encouraged him to explore photomontage and Surrealist ideas.

She pushed back on his dominance, which both attracted and infuriated him.

5. Their Relationship Was Intense — and Destructive. Their emotional connection ran deep, but it was full of psychological games and power struggles. Picasso said Dora had the “face of sorrow”, and he often depicted her in pain — which mirrored the emotional toll of their relationship.

Dora later said: “I wasn’t Picasso’s mistress. He was mine.”

6. She Witnessed the Making of Guernica. Dora not only photographed the process of Guernica (1937), Picasso’s protest painting against fascism — she also influenced its visual intensity.

Her emotional state, grief over Spain, and surrealist vision shaped Picasso’s imagery of anguish and disfigurement.

7. Picasso Left Her for a Younger Woman. In the early 1940s, Picasso began seeing Françoise Gilot, who was decades younger. Dora fell into a deep depression, suffering a mental breakdown, and was treated with electroshock therapy.

She withdrew from the art scene and became increasingly reclusive, turning to Catholic mysticism and solitude.

8. She Found Peace — and Reclaimed Herself. After years of suffering, Dora resumed painting in a very private, meditative style. She lived alone in Paris, rarely spoke of Picasso, and refused to sell his artworks — keeping them hidden until her death in 1997.

She once said: “After Picasso, only God.”

9. He Painted Her for Years — Even After It Ended. Picasso painted Dora over 140 times, many of them harsh, contorted, or sad.

Even when they were no longer together, her image haunted his canvases.

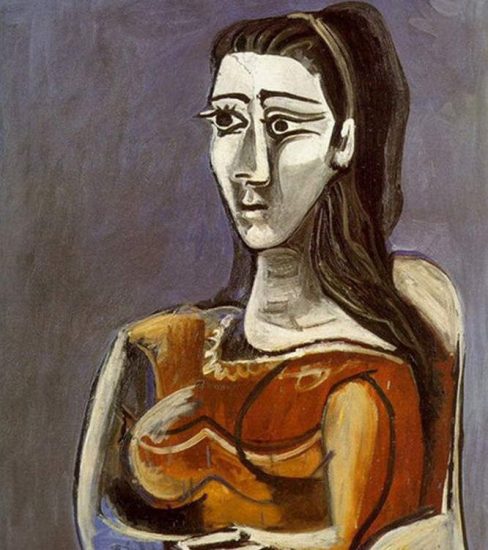

Picasso Muse Françoise Gilot (In Picasso's life from 1943-1953)

Never seeming to be satisfied, in 1943, Pablo Picasso wooed the 21-year-old law student and aspiring painter Françoise Gilot for months. His works of her are filled with a light color palette and sense of youth and longing as can be seen in Portrait of Françoise (1946), Woman Flower (1946), Femme au Collier jaune (1946) and Woman in an Armchair I (1948).

In love and deeply dedicated to Picasso, Françoise bore him two children, a son, Claude, and a daughter, Paloma Picasso. He was delighted, but Françoise soon became resentful of the abuse and his constant philandering, sinking into depression. Tired of the life and Picasso, it was in 1953 when Françoise left Picasso and married a year later.

Publishing Life with Picasso in 1964, Françoise’s memoirs enraged Picasso and prompted him to sever all ties with her. After marrying again in 1970, she currently resides in New York.

Facts about Picasso's Muse Françoise Gilot

Picasso’s relationship with Françoise Gilot stands out as one of the most remarkable chapters in his life, not just because of the age gap or her role as his muse, but because she was the only woman who ever left him — and then thrived. Their relationship was filled with creativity, complexity, and a powerful struggle for independence.

- Their Love Began in the Shadow of War and Art. Picasso met Françoise Gilot in 1943, during the German occupation of Paris. She was 21, a student of literature and painting. He was 61, already world-famous and still involved with Dora Maar.

Gilot described him as “a magician,” and he described her as having “the gift of not being overwhelmed by me.”

2. They Lived in the South of France — Surrounded by Art and Chaos. After the war, they moved to Vallauris, a sleepy town in the South of France. Their home, La Galloise, became a creative hive: Picasso painted, made ceramics, and drew constantly.

Gilot lived among the constant whirl of models, animals (goats, owls, children, and friends — but also Picasso’s obsessive need to control everything.

3. They Had Two Children Together. In 1947, their son Claude Picasso was born. In 1949, their daughter Paloma Picasso followed (she would later become a celebrated fashion designer and jeweler).

Despite Picasso’s affection for his children, he refused to legally recognize them at first — out of spite toward Françoise and his wife Olga, from whom he never divorced.

4. They Worked Side-by-Side — But On Unequal Terms. Françoise painted alongside Picasso and was treated as both pupil and muse. He encouraged her work — but only to a point. He once told her:

“There are only two kinds of women — goddesses and doormats.”

She replied:

“And I intend to be neither.”

Her resistance fascinated him — but he could never quite accept her independence.

5. He Introduced Her to the World of Giants. Through Picasso, she met Matisse, Braque, Chagall, Cocteau, and Giacometti.

Picasso used his immense influence to help and hinder her:

He encouraged her work privately, but undermined it publicly, fearing she would outshine him.

6. Infidelity and Control Strained Their Life. Picasso began seeing Jacqueline Roque in secret in the early 1950s. Gilot grew weary of his need to dominate, his shifting moods, and his emotional cruelty.

He mocked her independence, saying:

“You imagine people care what you paint. You’re a woman — and women are always secondary.”

7. She Did the Unthinkable — She Left Him. In 1953, after a decade of artistic collaboration and domestic tension, Gilot left Picasso. She was the only woman ever to leave him voluntarily.

He was enraged and warned her:

“If you leave me, I’ll ruin you.”

He blacklisted her in galleries, spread rumors, and refused to let their children carry his name — for years.

8. She Published a Memoir — and the World Listened. In 1964, Gilot published Life with Picasso, co-authored with Carlton Lake. The book revealed intimate, day-to-day life with the artist: his brilliance, cruelty, humor, and contradictions.

Picasso tried to block its publication and never forgave her — but the book became a bestseller and secured her own artistic voice.

9. She Reclaimed Her Career — and Thrived. After leaving Picasso, Françoise pursued her own artistic path, developing a unique, lyrical, and philosophical style. Her exhibitions spanned New York, Tokyo, Paris, and London.

She taught, lectured, and was honored by museums around the world.

10. She Found Love and Peace Elsewhere. In 1970, she married Jonas Salk, the American scientist who developed the polio vaccine — a true partnership based on mutual respect. She lived between the U.S. and France, continuing to paint well into her 90s.

Françoise lived to be 101 years old, passing away in 2023 — long after Picasso, whose shadow she ultimately outgrew.

Picasso Muse Genevieve Laporte (In Picasso's life from 1951-1953)

While living with Françoise, 24-year-old Genevieve Laporte visited the 70-year old Pablo Picasso at his studio and a love affair began. She declined Picasso’s invitation to move in with him and left him in 1953 at the same time that Françoise left the artist.

In 1972 she went public with the affair and in 2005, auctioned 20 drawings of herself that Picasso created during their secret affair such as Portrait of Genevieve Laporte (1951). Picasso’s work during this time is known as his “tender years” as they mainly revolve around his children and lighter subjects as can be seen in Paloma a l`orange (1951), Genevieve à la jacquette rayee (1951), Claude ecrivant (1951), Wood Owl Woman ceramic (1951) and Colombe volante (a l`Arc-en-ciel) (1952).

Facts about Picasso's Muse Genevieve Laporte

Picasso’s relationship with Geneviève Laporte is one of the lesser-known, but deeply revealing, chapters of his later romantic life. Their connection was marked by tenderness, secrecy, and poetry — both literal and emotional.

- She Was a Poet and Interviewed Him as a Teenager. Geneviève Laporte first met Picasso in 1944, when she was just 17. She was a literature student and aspiring poet, and interviewed him for a school magazine. Their first meeting was friendly and respectful — he called her “Mademoiselle la Poésie.”

She would later write: “I came to interview the painter, and I met a man who saw into the heart of silence.”

2. Their Love Affair Began a Decade Later. In 1951, when she was 24 and Picasso was 70, their friendship blossomed into an affair. At the time, Picasso was still living with Françoise Gilot, but that relationship was nearing its end. Geneviève and Picasso spent quiet time together in Paris and later the South of France.

Their bond was built less on explosive passion and more on shared solitude, nature, and poetry.

3. They Shared an Intimate Summer in Saint-Tropez. In 1951, Picasso invited Geneviève to join him for a secluded summer at his villa in Saint-Tropez. They spent days painting, swimming, and walking — away from the public and Picasso’s usual entourage. She later described it as the happiest, most peaceful time of her life.

He painted her — not as a contorted muse, but as a gentle, graceful presence.

4. She Inspired a Softer Side in His Art.Picasso’s works during their time together reflect calm, affection, and lyricism. He created a series of drawings and sketches of her that emphasized tenderness, rather than torment.

Unlike Dora Maar or even Gilot, Geneviève did not engage in intellectual battles with Picasso — she offered him a quiet kind of intimacy.

5. She Refused to Replace Gilot. After Gilot left Picasso in 1953, he asked Geneviève to move in with him permanently.

She declined, saying:

“I would have had to give up my life, my poetry, my freedom — and I wasn’t willing to.”

This refusal stunned Picasso, who was used to women orbiting around him.

6. She Later Published Memoirs of Their Time Together. Geneviève Laporte wrote several books about her life and time with Picasso:

- “Moi, Picasso” (1993)

- “Si tard le soir le soleil brille”

- “Un amour secret de Picasso”

Her memoirs are noted for being gentle and poetic, offering a softer, more human view of Picasso.

Unlike other muses, she neither attacked him nor idolized him — she observed him.

7. She Preserved His Gifts — and Later Sold Them for Charity. Picasso gifted her numerous drawings and sketches, many of which she kept for decades. In 2005, she auctioned some of them to fund a foundation for art and poetry — combining their shared loves.

The works sold for millions.

8. She Remained Gracefully Private. Unlike Françoise Gilot, Geneviève did not seek public confrontation or literary revenge. She continued writing poetry and resisted being defined solely as Picasso’s lover.

She passed away in 2012, quietly celebrated as one of the few women who knew Picasso without being consumed by him.

Geneviève’s story is particularly powerful because she wasn’t just a muse or mistress — she was a mirror of calm during a lifetime of storms.

Picasso Muse Jacqueline Roque (In Picasso's life from 1953-1973)

Alone and dejected, Pablo Picasso met the 27-year-old Jacqueline Roque at the studio where he created his Madoura Ceramics in 1953. Rebuking his advances at first, Jacqueline became consumed with Picasso, looking upon him as a God. In 1961, at the age of 79, he married her, though still continued to take other lovers.

During his 20 years with Jacqueline, he painted more than 400 pictures of her and created countless ceramics. It was a period of intense creativity with works such as Jacqueline with Flowers (1954), Jacqueline in Studio (1956), Jacqueline Rocque (1957), Portrait de Jacqueline (1957), Femme assise (1960), Jacqueline Getting Married (1961), Jacqueline`s Profile (1962) ceramic and Femme assise (Jacqueline) (1971).

Towards the end of Picasso’s life he became almost a hermit, which his friends blamed on the possessiveness of Jacqueline, who even barred his children and grandchildren from their house for the sake of preserving Picasso’s creative space. Picasso died in 1973 with Jacqueline right by his side and thirteen years later, she shot herself, having finally felt she secured his everlasting legacy.

Picasso left an impact on all of his women, positive and negative, but they in turn impacted him: his creativity, his art, and his life. He was by no means kind or faithful, but always expressed his feelings for them in his art, always drove himself to do better to show them, which is his lasting legacy. Without a specific lover to inspire at the right time, would those great works of art we hold dear today exist? It’s possible Picasso’s entire career could have shifted without the women he surrounded himself with and this is a testament to them, for they are not simply muses or lovers, but partners in his storied legacy and deserve the recognition.

Facts about Picasso's Muse Jacqueline Roque

Picasso’s relationship with Jacqueline Roque, his last and longest-lasting partner, was a mixture of devotion, dependence, and isolation. She was the woman who shared the final 20 years of his life, became his second wife, and ultimately controlled his legacy — for better or worse.

1. Meeting and Courtship. Jacqueline Roque met Picasso in 1953 at the Madoura pottery studio in Vallauris, France. She was 26 years old, Picasso was 72.

Picasso courted her intensely, famously leaving daily roses at her doorstep.

2. Marriage. They married in 1961; Jacqueline was Picasso’s second and final wife.

This was Picasso’s only legal marriage, as he never divorced his first wife Olga Khokhlova.

3. Muse and Inspiration. Jacqueline was Picasso’s most painted muse, appearing in over 400 artworks.

She inspired much of his late style, including portraits marked by bold lines and vivid colors.

4. Life Together. The couple lived primarily in Notre-Dame-de-Vie, a villa in Mougins, southern France. Jacqueline was devoted, acting as his caretaker and gatekeeper, often shielding Picasso from outside visitors.

5. Relationship Dynamics. Their relationship was marked by intense devotion but also isolation. Jacqueline was fiercely protective, which led to strained relationships between Picasso and his children.

6. Family. Jacqueline had one daughter, Catherine, from a previous marriage. Picasso never formally adopted her, but Catherine became involved in managing his estate later.

7. After Picasso’s Death.Picasso died in 1973. Jacqueline kept control of his estate but had difficult relations with his children.

She barred some family members from his funeral, causing tension.

8. Tragic End. Jacqueline Roque died by suicide in 1986, 13 years after Picasso’s death.

She was reportedly deeply affected by his passing and her isolation.

REFERENCES:

- Duncan, David Douglas. The private world of Pablo Picasso. New York: Harper & Bros., 1958.

- http://www.pablo-ruiz-picasso.net/

EXHIBITIONS CENTERING ON PICASSO AND HIS MUSES:

- Picasso: The Artist and His Muses. Vancouver Art Gallery, Canada.

- November 1, 2013 – February 24, 2014. The Modern Muse. Hammer Galleries, New York.

- June 25-October 27, 2013. Picasso: Nudity Set Free. Centre d’art La Malmaison at Cannes.

- April 14 – July 15, 2011. Picasso and Marie-Thérèse. L’amour fou. Gagosian Gallery. New York.

- 2010-2012 Picasso – Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris. (Traveling Exhibition)

BOOKS CENTERING ON PICASSO AND HIS MUSES:

Please enjoy our collection of Pablo Picasso portraits.

Read about famous art about gender equality.