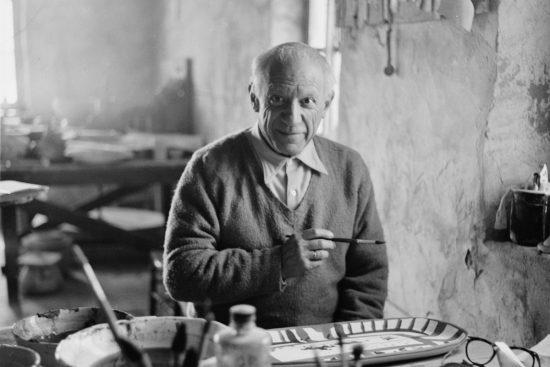

Vallauris — the small town in the Alpes-Maritimes region of southern France — became a magnet for artists in the mid-20th century, especially after Pablo Picasso finally settled there in 1948. Drawn by its lonlg tradition of pottery making, mild climate, and proximity to the Côte d’Azur art scene, Vallauris turned into a creative hub where painters, sculptors, and ceramicists mixed freely.

In the late 1940s–1960s, the town’s pottery workshops swelled with both resident artisans and visiting artists from across Europe, making Vallauris one of the most important post-war centers for modern ceramics.

First visiting in 1946, was captivated by the earthy allure of clay and the vitality of the local artisans. While visiting the annual pottery exhibition in Vallauris, Pablo Picasso had the good fortune to meet Suzanne and Georges Ramie. The Ramies owned the Madoura workshop, a ceramics studio in Vallauris, where he, who was eager to delve into a new medium, made his first venture into ceramics.

Picasso became so enthralled with ceramics that he decided to move to Vallauris to pursue his new passion.

Over the next two decades, Picasso produced thousands of works—plates, pitchers, tiles, and sculptures—that merged functional craft with avant-garde vision, infusing Mediterranean light, ancient myths, and his own playful imagination into each piece. His presence drew a constellation of talent, from the actor-turned-sculptor Jean Marais to innovative ceramicists like Gilbert Portanier, Robert Picault, Juliette Derel, Roger Capron, and André Baud, turning Vallauris into a crucible of creativity. Beyond the studio, Picasso left an indelible civic mark, gifting the monumental mural War and Peace to the town’s Chapel of the Castle and embracing the rhythms of local life, often mingling with residents at village festivals. Through his fame and prolific output, Vallauris became an international center for contemporary ceramics during the 1950s and 1960s, attracting collectors, critics, and artists from around the globe—a legacy that endures in the town’s identity, where the hum of the kiln still seems to carry whispers of Picasso’s transformative touch.

Was Picasso looking for a Pottery studio?

Picasso first came across Vallauris in 1946, not by deliberate search but almost by artistic happenstance. That summer, he was in nearby Golfe-Juan with Françoise Gilot, and he visited the annual pottery exhibition in Vallauris. Suzanne and Georges Ramié invited him to try his hand at their kilns, and within days he had produced a handful of decorated plates—an experience that reignited his fascination with three-dimensional form and craft. For Picasso, ceramics offered a new frontier: tactile, sculptural, and deeply rooted in the Mediterranean heritage he loved. That serendipitous encounter led him to return in 1947, and by 1948, he had moved to Vallauris permanently, setting the stage for one of the most prolific and playful chapters of his career.

Where did Picasso live in Vallauris?

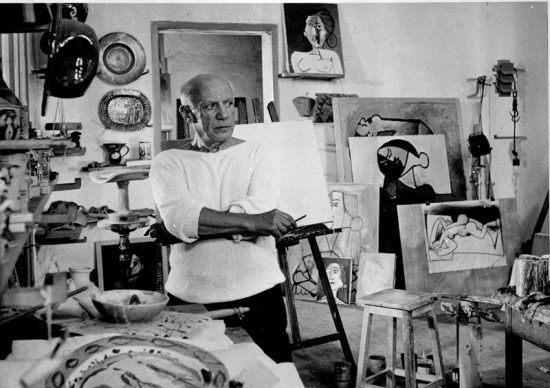

Picasso initially bought and transformed Les Fournas, a former perfumery in Vallauris, into his studio, where he worked prolifically.

Once settled, Picasso lived at Mas Notre-Dame-de-Vie, a historic farmhouse he rented starting in 1948. Picasso’s Mas Notre-Dame-de-Vie was more than just a residence—it was a sanctuary for relentless creativity. The rustic Provencal farmhouse, with its thick stone walls and terracotta roof, opened onto courtyards and gardens where sunlight poured generously into every corner, illuminating canvases, sketches, and sculptures alike. Inside, the spaces were organized to mirror the flow of his imagination: a dedicated ceramics workshop, with potter’s wheels, kilns, and shelves crowded with clay, glazes, and experimental pieces, buzzed with the quiet energy of creation, while separate corners of the house displayed his paintings and drawings, stacked against walls or perched on easels, ready for his ever-shifting attention. Outdoors, the gardens served as both gallery and workspace, where large clay figures could dry under the Provencal sun, and where the Mediterranean landscape itself became muse. The studio was alive with the messy, tactile pulse of artistry, a reflection of Picasso’s boundless curiosity, where painting, sculpture, and ceramics intertwined in a harmonious, daily symphony of innovation.

This Provencal-style property became both his home and studio, giving him ample space to work on ceramics, paintings, and sculptures. The farmhouse had a large garden and workshop areas, allowing him to experiment freely with clay and other materials.

It’s worth noting that while Mas Notre-Dame-de-Vie was his main residence in Vallauris, he also spent time in other studios in the region, particularly when collaborating with local potters or exploring nearby landscapes for inspiration.

Pablo Picasso purchased Mas Notre-Dame-de-Vie in 1961 as a wedding gift for his second wife, Jacqueline Roque. The estate, located in Mougins, France, became his final home and studio, where he lived until his death in 1973.

The property was previously owned by Thomas "Loel" Guinness, a member of the Anglo-Irish Guinness brewing family. Picasso's acquisition of the estate marked the beginning of a new chapter in his life and artistic journey.

In 2017, the estate was sold at auction for €20.2 million (approximately $24 million), a price considered a bargain by some experts.

Today, the estate is known as Château de Vie and has been refurbished to become a private collection, while keeping as close as possible to the original house as it was during Picasso's time.

Where did Picasso meet Jacqueline?

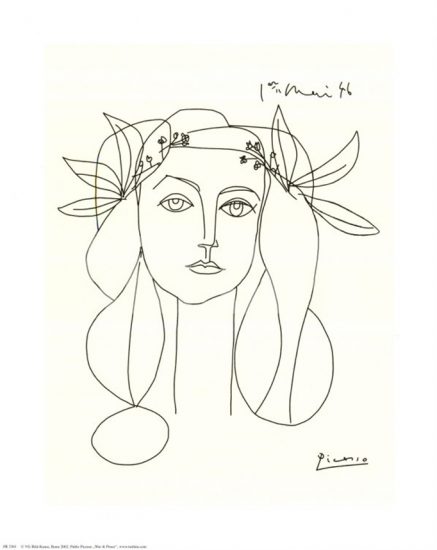

Picasso met Jacqueline Roque in 1952 at the Madoura Pottery in Vallauris, where she was working as a sales assistant. At the time, Picasso was already deeply involved in creating ceramics there, and Jacqueline often helped artists and customers select pieces. Their first meeting was quiet but memorable—Picasso, then 71, began courting her persistently, famously leaving a rose on her desk every day for months. Their relationship grew over the following years, and after the death of Françoise Gilot’s mother in 1954, Jacqueline became Picasso’s constant companion. She would go on to be his muse for more than two decades, appearing in hundreds of paintings, drawings, and prints, and in 1961, the two married.

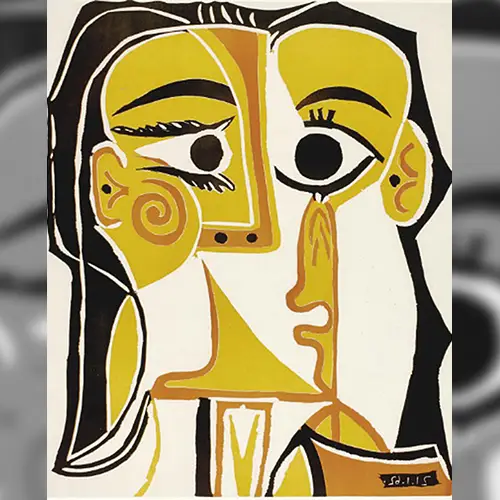

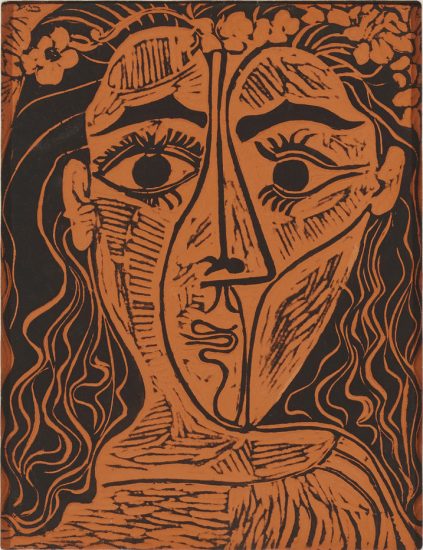

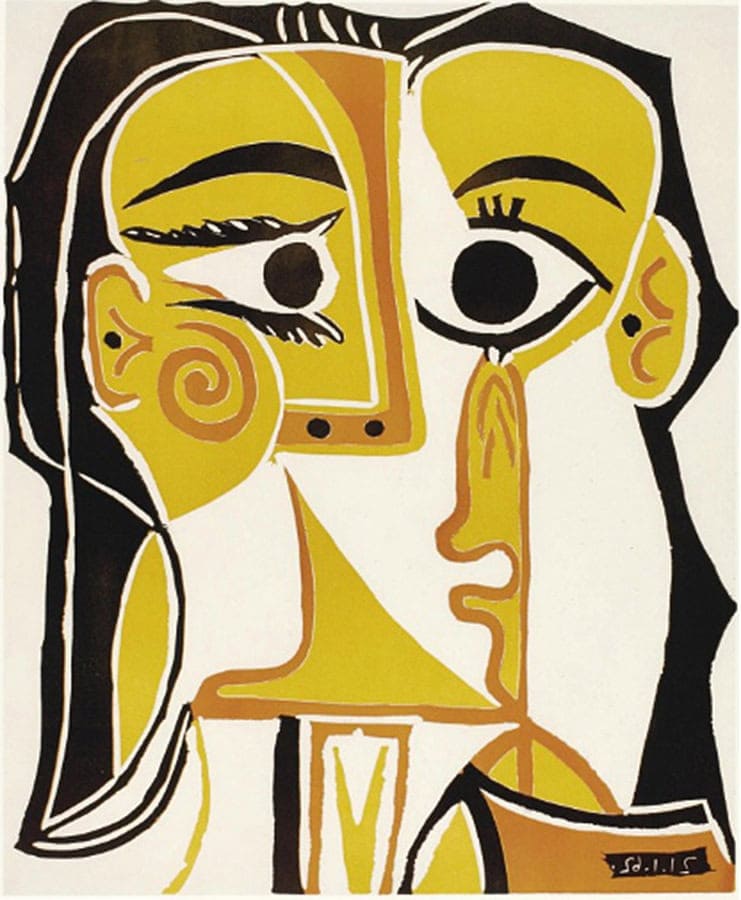

Pablo Picasso, Tête de Femme (Head of a Woman), 1962

Picasso’s creation of La Guerre and La Paix

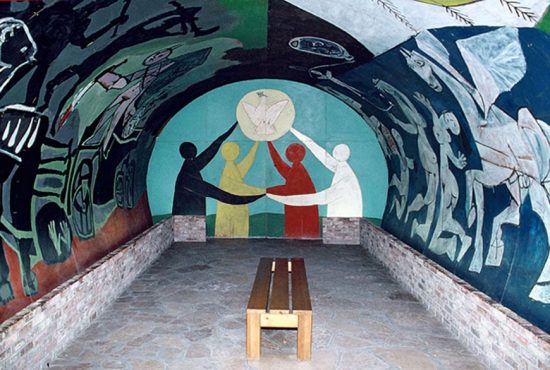

Between 1952 and 1954, Pablo Picasso undertook the creation of his monumental frescoes La Guerre (War) and La Paix (Peace) in Vallauris, a profound artistic endeavor that reflected both his personal convictions and the turbulent context of the post-World War II era. Installed on the vaulted ceiling of the former 12th-century Romanesque chapel of Vallauris Castle, these frescoes were conceived as a meditation on humanity’s capacity for both destruction and reconciliation. Picasso, deeply moved by the atrocities of war and the looming anxieties of the Cold War, sought to convey through bold, expressive forms the stark contrast between the suffering caused by conflict and the restorative hope offered by peace. His choice of the chapel, with its austere architecture and sacred proportions, amplified the emotional and symbolic weight of the works, transforming the space into a sanctuary of reflection. La Guerre depicts the horrors and anguish of armed conflict with striking intensity, while La Paix radiates a sense of harmony and renewal, illustrating Picasso’s enduring belief in the power of art to inspire moral and social consciousness. The frescoes stand today not only as masterful works of visual art but as timeless testaments to Picasso’s engagement with the ethical and political challenges of his time, immortalizing his vision of a world poised between violence and hope.

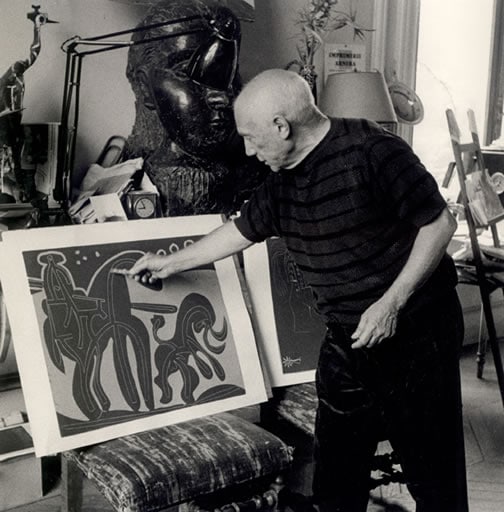

Picasso worked extensively, creating many ceramics, sculptures, linocuts, and paintings, including his masterpiece “War & Peace”, a diptyque that was installed in the chapel of the Château de Vallauris in 1959. It was also in Vallauris where Picasso first developed a fascination with two mediums: ceramics and linocuts.

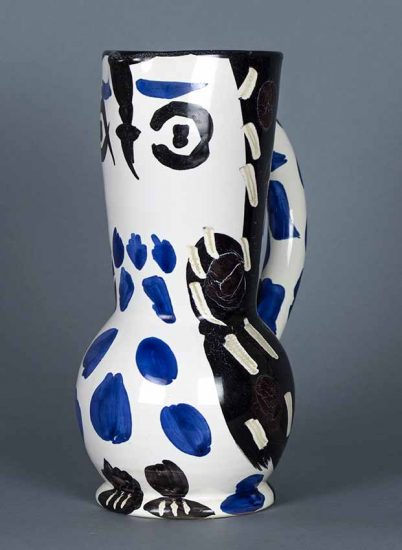

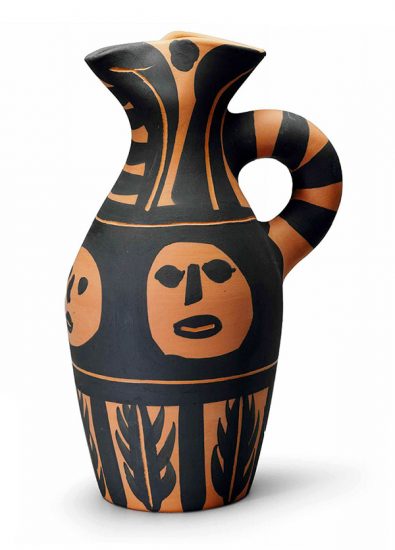

Picasso loved the malleability of clay and the fiery firing process, which transformed clay into stunning works of ceramic art. He experimented with varied shapes, forms, textures, enamels, and glazes, innovating the ceramics medium. Picasso’s approach was anything but conventional- he would melt clay like bronze, fashion mythical creatures directly in the glaze, and tirelessly decorate plates and dishes with his favorites subjects, such as bullfights, women, owls, goats, fauns, and fish. He incorporated surprising and innovative materials into his craft and invented white paste, which is a ceramic that has not been glazed and decorated with pieces in relief. These white paste works are amongst the most stunning and desirable Picasso ceramics to date.

Picasso went on to create thousands of ceramics in the Madoura ceramic studio. Incollaboration with Suzanne and Georges Ramie and the skilled ceramicists at the Madoura studio, Picasso shaped plates, dishes, vases, jugs, and other earthenware utensils and then painted and decorated them with enamel and metal oxides. Picasso was particularly fascinated by the use of metal oxides, as their very nature meant that he never quite knew how the end product would look.

Just as Picasso collaborated with master printers to create editions of his printed works, Picasso collaborated with Suzanne and Georges Ramie to create set editions of his ceramic works. Today, these Picasso ceramics are amongst the most valuable and desirable works of Picasso’s entire artistic oeuvre. The diversity of form and range of subject matters found within Picasso ceramics lend them a rareness and unique charm that contributes to their increased demand in the art market.

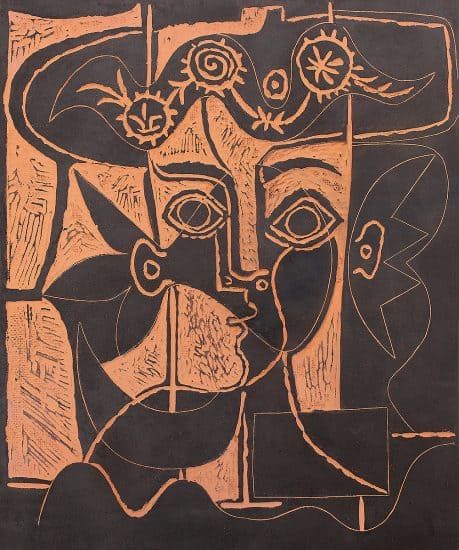

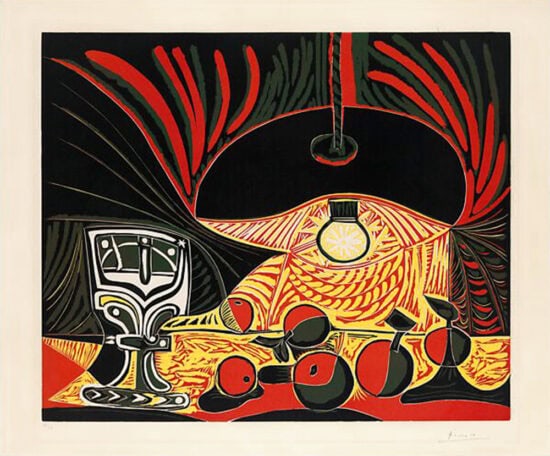

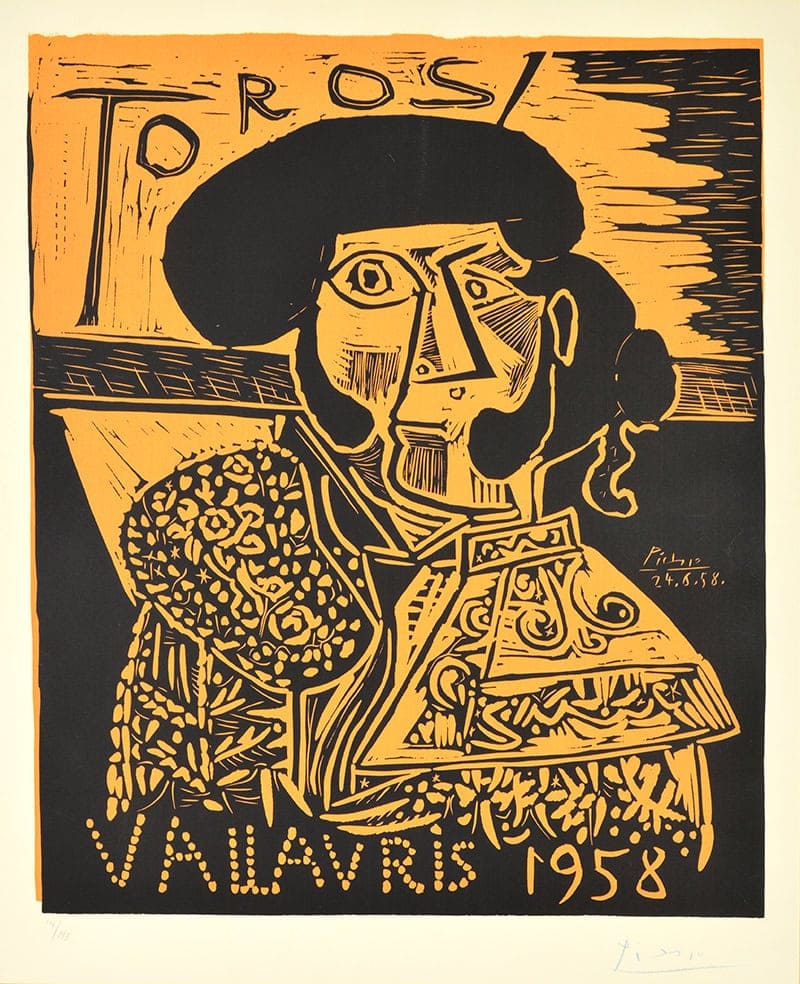

In addition to ceramics, Picasso also became fascinated with the linoleum cut (or linocut) medium while living in Vallauris. Printer Hidalgo Arnera introduced Picasso to the linocut medium, initially suggesting linocuts as a suitable medium for producing posters. However, in his trademark fashion, Picasso pushed the boundaries of the linocut medium, creating astounding linocuts that remain amongst his most renowned and valuable prints to date. While Picasso’s first linocuts were used as posters to advertise the bullfights and ceramic exhibitions in Vallauris, he quickly transformed the linocut medium into a unique form of expression unlike anything the world had every seen, predominantly by placing increased emphasis on color and form.

Linoleum cuts (or linocuts) are a type of relief printmaking in which the artist-engraver cuts into a linoleum block to form a design. The remaining negative surface is then inked and printed. Desirable for their boldly graphic compositions, delightful use of ornamental patterns, expressive treatment of color, and superior handling of line, Picasso linocuts are collectible for their vibrant imagery and as relics of Picasso’s cherished time spent in Vallauris.

Picasso was an iconic and important figure in Vallauris’ history. He became a freeman of Vallauris and greatly contributed to the renaissance of the Vallauris pottery industry in the 1950s. Picasso also demonstrated his commitment to civic duty by creating linocut posters for Vallauris’ annual ceramic fairs and bullfights.

Following Picasso’s departure from Vallauris in 1955, Vallauris remained an important part of Picasso’s life. He retained fond memories of his time spent living in Vallauris, where his lover Francois Gilot and their children Claude and Paloma Picasso often accompanied him. Picasso would return to Vallauris at later points in his life to revisit the bullfights, exhibitions, and old friends and acquaintances. In fact, Vallauris was so dear to Picasso that he married his second wife Jacqueline Roque in great secrecy at the Vallauris town hall in 1961.

Picasso’s presence in Vallauris shaped the town’s history. Following his move there, other artists, such as Victor Brauner and Marc Chagall, rushed to work in the ceramic studios in Vallauris. Today, the Musee National Picasso in Vallauris pays homage to the artistic inspiration and personal happiness that Picasso found in Vallauris.

What other fruits did Picasso in Vallauris bear?

Picasso is best known for his ceramics, but he did much more while living there.

- Painting and Drawing: Picasso continued creating paintings, often experimenting with bold colors, abstract forms, and themes inspired by Mediterranean life. He sometimes integrated motifs from ceramics into his paintings.

- Sculpture: He explored small-scale sculptures, working with materials like plaster, wood, and metal. Some of these sculptural experiments were influenced by the shapes and techniques he used in his pottery.

- Printmaking: During this period, he produced etchings and lithographs, many reflecting his interest in bullfighting, clowns, and mythology—subjects he also explored in ceramics.

- Collaboration and Teaching: Picasso occasionally collaborated with local artisans, sharing ideas and techniques. His presence in Vallauris helped transform it into a hub for contemporary ceramics.

- Community and Exhibitions: He participated in local exhibitions, helping to bring international attention to the town’s ceramic industry. His work in Vallauris blended artistic experimentation with a practical engagement with craft and local culture.

Picasso Museum in Vallauris

The Musée National Picasso – La Guerre et la Paix in Vallauris officially opened in 1959, following Pablo Picasso’s donation of his monumental frescoes La Guerre and La Paix to the French state. These works, painted between 1952 and 1954 on panels of hardboard, were installed in the former Romanesque chapel of Vallauris Castle, a 12th-century building that Picasso chose for its symbolic and austere proportions. The chapel's architecture contributed to the sacred and universal anchoring of the frescoes, which reflect his reflections on the devastation of war and his enduring hope for peace.

The museum was established to honor Picasso's legacy in Vallauris, where he lived and worked from 1948 to 1955. In recognition of his contributions to reviving the art of pottery in the region, the town of Vallauris gave Picasso the château in 1955. This gesture laid the foundation for the museum, which is located in the immediate vicinity of the Magnelli municipal museum and the Musée de la Céramique, forming a cultural hub in the town.

Today, the museum continues to celebrate Picasso's connection to Vallauris, showcasing his works and the artistic environment he helped foster in the town. The upcoming reopening of the Madoura Pottery workshop as a museum in 2027 will further enhance the town's dedication to preserving and sharing Picasso's artistic heritage.

Pablo Picasso, Jacqueline au chevalet (Jacqueline at the Easel) Ceramic, 1956

Did Picasso Bullfights in Vallauris?

While living in Vallauris, Picasso frequently attended bullfights, captivated by the drama, power, and symbolism of the arena. The bull became a central motif in his paintings, ceramics, and drawings, embodying strength, struggle, and vitality, and reflecting the town’s vibrant cultural traditions that so deeply inspired his work.

Pablo Picasso, Toros Vallauris (Bulls in Vallauris), 1958

Where did Picasso eat in Vallauris?

While residing in Vallauris from 1948 to 1955, Pablo Picasso frequented several local establishments, reflecting his integration into the town's community and his appreciation for its culinary offerings. One notable venue was Restaurant Le Vallauris, where Picasso hosted a luncheon for friends, including Jean Cocteau, before attending a bullfight in 1955.

Additionally, Picasso was known to dine at Le Nérolium, a local establishment that also served as a venue for pottery exhibitions. This place was significant in Picasso's life, as it was during a visit to an exhibition there in 1946 that he discovered the Madoura Pottery Workshop, leading to his deep involvement in ceramics.

During his years in Vallauris, Pablo Picasso extended his artistic exploration beyond painting and ceramics into the realm of metalwork, producing a remarkable series of gold medallions that reflect both his inventive spirit and his engagement with the town’s artisan traditions. At the Madoura Pottery studio, surrounded by skilled craftsmen adept in casting and engraving, Picasso experimented with the intricate process of designing and creating medallions in gold and bronze, transforming these small, precious objects into intimate canvases for his imagination. Each medallion often bore motifs familiar from his broader oeuvre—bulls symbolizing strength and vitality, doves expressing peace, mythological figures, or stylized portraits of women—capturing the same symbolic richness and playful inventiveness that marked his larger works. The collaborative environment of Vallauris, with its centuries-old heritage of pottery and metal craftsmanship, allowed Picasso to merge traditional techniques with his own visionary designs, elevating everyday materials into works of art imbued with both aesthetic beauty and cultural resonance. These medallions stand today not only as exquisite examples of Picasso’s technical versatility but also as tangible expressions of his intimate dialogue with Vallauris, a town that nurtured his curiosity and creativity during a transformative period in his life.

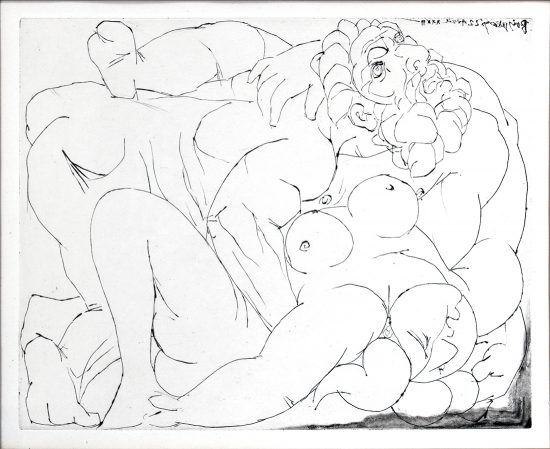

Pablo Picasso, Joueur de flute et cavaliers (Flute Player and Cavaliers)

- Dalloz, J.D. (2013). Picasso in Vallauris.

- Euromaxx Series Following in Picasso’s Footsteps: Vallauris [Video file]. (link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cIxWQoeP2p8)

- Musee National Picasso (2014). Picasso. (link http://www.musees-nationaux-alpesmaritimes.fr/en/picasso/le-musee/picasso-a-vallauris/)

- Vallauris Golfe-Juan Cote d’Azur (2014). Picasso.

- Picasso and the Madoura Ceramic Studio

- Luxury Gift Ideas: Fine Art