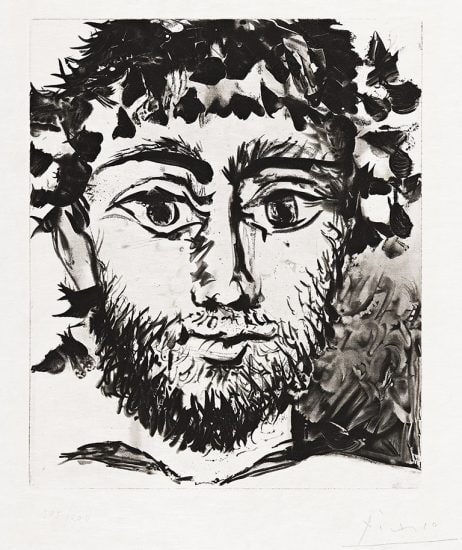

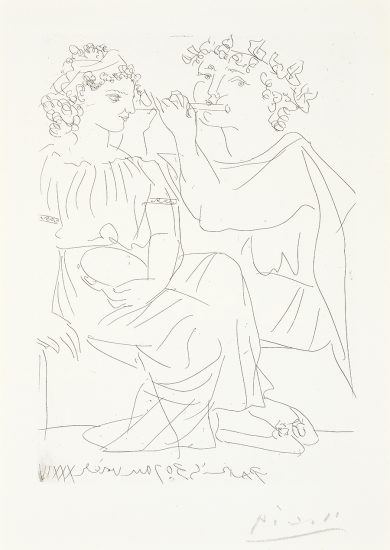

Pablo Picasso, one of the most famous visual artists in history, is renowned for his innate artistic skill and pioneering Cubism alongside Georges Braque. The artist worked through multiple series throughout his career, his Blue Period arguably his most celebrated; lesser known, but just as striking, is his Ninfe e Fauni (Nymphs and Fauns) series. This particular body of work is inspired by the legendary beings of Greek mythology such as the Minotaur, centaurs and fauns which are often rendered in glass with the help of master glassmakers Egidio Constantini and Ermanno Nason. Though this series is limited to glass works, imagery of Greek mythological creatures is a frequent motif in much of Picasso’s other work as well.

The influence of ancient Greece is a recurring theme in academic painting and sculpture before the 20th century. With the arrival of the modern art movement in the 1900s, this influence transformed into something largely disparate from the antecedent scope of art history; we see this transformation through Picasso’s work across the span of his lifetime. Modernism as a movement strayed drastically from the foundation of classical art-making which was, for the most part, dedicated to realistic representation. With the popularization and growing convenience of documentary photography in the 20th century, artists were forced to explore alternative methods of making that could not be realized with a camera. The value of realism dwindled as modernism became the new standard. In his works, Picasso references his own disengagement and subversion of the discourse of classical art history by recreating images of traditional Greek figures in a modern fashion. The artist once famously remarked “, It took me four years to paint like Raphael, but a lifetime to paint like a child.”

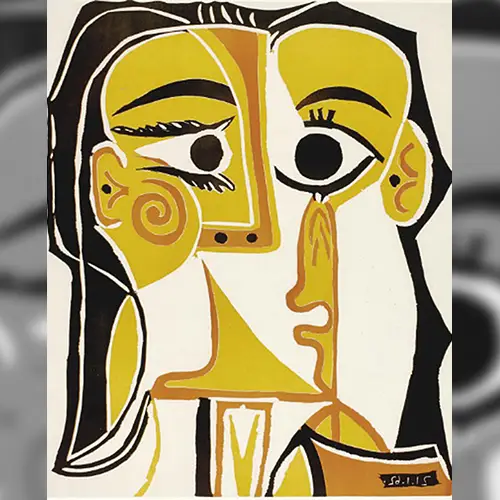

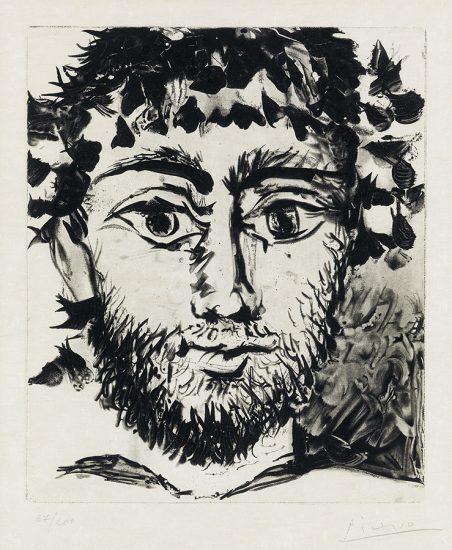

Though his depictions of mythological creatures are unconventional and stray from pragmatic representation, they still retain the dynamism and demand a similar reverence as the original renditions. Much of Picasso’s work can be characterized by an urgency in his mark-making and a whimsical, childlike sensibility. His work revolving around Greek mythology, from prints to ceramics to glass, maintains these aspects of the artist’s style but it also often contains a much greater commitment to attention to detail. This type of rendering pays respects to the foundation that the Greeks gave us while reinstating their influence in the modern art world.

Ancient Greek art is extremely studied, patient, and sensible which starkly contrasts Picasso’s credence that “, the chief enemy of creativity is ‘good’ sense.” Still, the artist dedicated a fair amount of his artmaking to recreating their mythological imagery; it must be inferred, then, that the Greeks had a great deal of influence on him on a level beyond visual. The dramatized visions of violence, love and power that compose Greek narratives brim with symbolism and nearly unmatched innovation. Picasso is one of the most famous artists in history due to his disregard for convention and his own creative capability; in mimicking the imagination of the Greeks, he preserves the heritage of artists who came before him and generates a new path in the trajectory of art history.