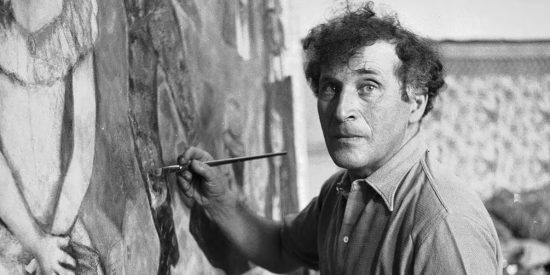

In honor of our showcase at the New York Art, Antique & Jewelry Show in New York at the Park Avenue Armory, September 17-21, 2014, we want to explore the impact New York Had on a Particular artist in our collection that we will be featuring there: Marc Chagall. Chagall called New York home from 1941-1948, while living there in exile during the events of World War II. There he created the most significant and revered works in his oeuvre that not only changed his career, but impacted his personal life as well.

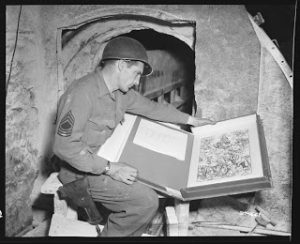

On the outbreak of World War II, Chagall was living in Nazi occupied France. At first, he refused to leave, believing that his fame as an artist would protect him. However, as the violence and persecution of the Jewish people escalated, Chagall realized that his attempts to remain in France were putting his family in grave danger. Therefore with the help of Alfred H. Barr Jr., the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, and Varian Fry, an American journalist who rescued European Jews and intellectuals, Chagall and his family fled to the safety of New York City in 1941.

Oil on Canvas

(© 2014 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris)

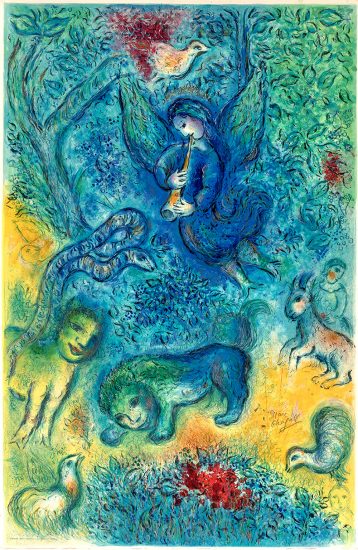

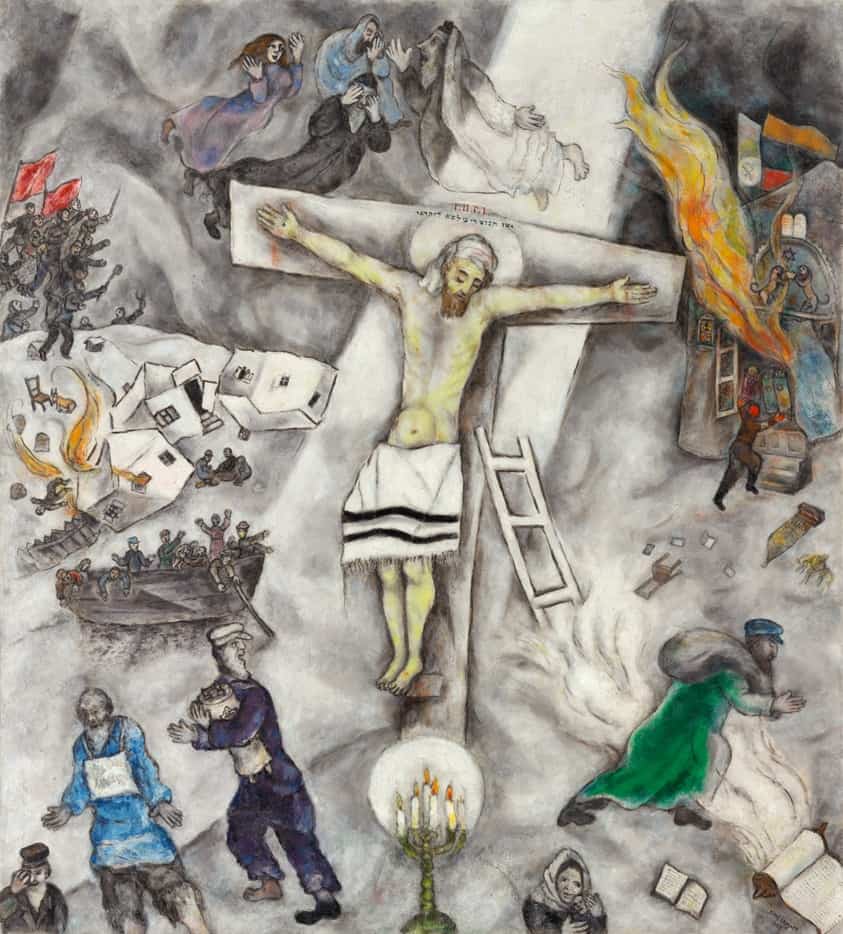

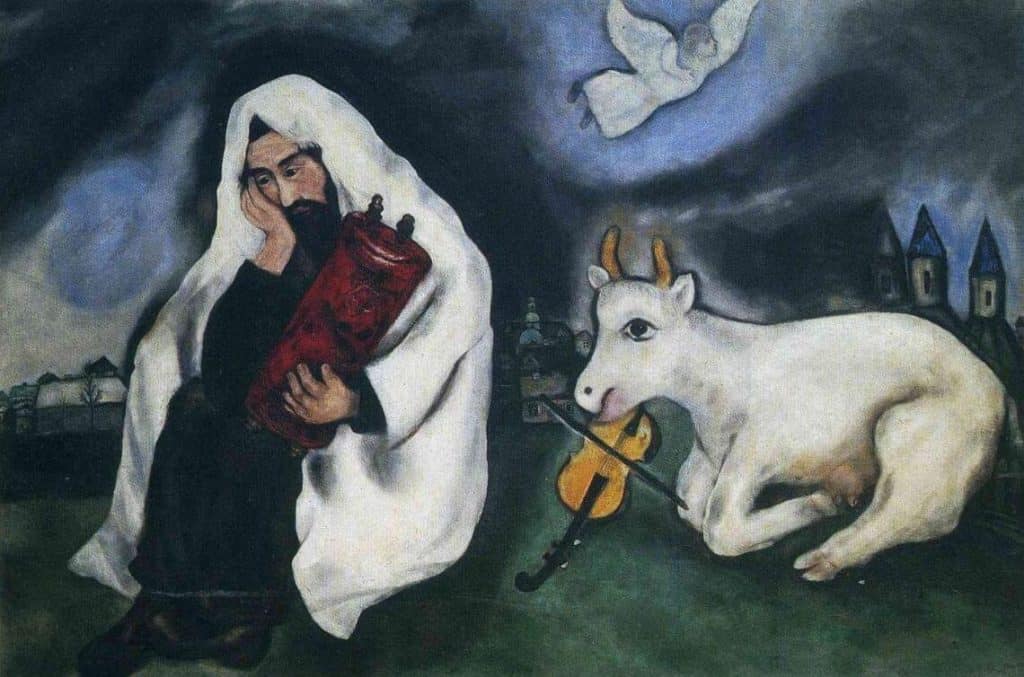

It was during this tumultuous time of persecution in France that Chagall’s religious themes became much more prevalent and vivid, which makes it important to note that this series of events is what inspires Chagall to portray Jesus as a Jewish martyr. For Chagall, Jesus on the cross was a symbol for victims of persecution, and an appeal to conscience that equated the martyrdom of Jesus with the suffering of the Jewish people. The strongest and first example of this symbolism is “White Crucifixion” (1938) where a crucified Jesus is being mourned by angels while a village is pillaged and burned, forcing refugees to flee while an accompanying scene of a synagogue and its Torah ark go up in flames and a mother comforts her child. It is strong imagery that passionately identifies the Nazis with Christ’s tormentors and warns of the moral implications of their actions. Meanwhile in stark contrast is a particularly touching work, the “Time is a River without Banks” (1930–1939), where Chagall blissfully portrays a place where no troubles exist and time simply does not matter for a couple wrapped in each other’s arms. A wishful remembrance of a simpler time that exists no more now that he was forced to consider his reality.

Oil on Canvas

(© ADAGP, Paris 2013 / CHAGALL ® © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN / Philippe Migeat)

Upon arriving in New York City, Chagall’s works lost their naive undertones all together and adopted a profound aura of torment. This is due to the torment he felt by news from Europe and the guilt and helplessness of exile. Unlike his years in France, Chagall was never completely comfortable in New York City. The artist felt disconnected from the places he understood best — Russia and Paris. He felt uncomfortable as a celebrity in a foreign country whose language he could not yet speak, and was lost in his strange surroundings. “Descent from the Cross” (1941) and “Obsession” (1943) both express this feeling of alienation and loss as Chagall channels the crucifixion into a personal reflection of himself as the suffering artist and as a continued expression of shocking traditional art.

Color Etching and Aquatint

(©Masterworks Fine Art Inc.)

Chagall did settle in though as New York was full of writers, painters, and composers who, like himself, had fled Europe during the Nazi invasions. He spent time visiting galleries and museums, and befriended other artists including Piet Mondrian and André Breton. In particular he enjoyed the Lower East Side, which had a large Jewish population, where he would spend hours every day feeling at home. It is always interesting to know that even though the museum and galleries adored Chagall’s art, his contemporary artists when he arrived did not yet understand or even like his art. That changed however, when Pierre Matisse, the son of recognized French artist Henri Matisse, became his representative upon his arrival.

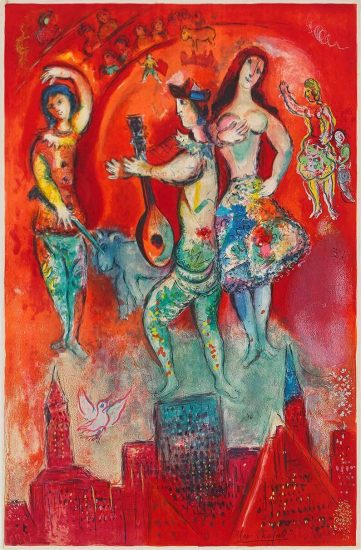

To further add to Chagall’s acclaim, in 1942, choreographer Leonid Massine, of the New York Ballet Theatre, commissioned Chagall to design the sets and costumes for his new ballet, Aleko. This ballet would stage the words of Pushkin’s verse narrative The Gypsies with the music of Tchaikovsky. It opened to critical acclaim, going on to open at the Metropolitan Opera, of which art critic Edwin Denby wrote, “…It surpasses anything Chagall has done on the easel scale, and it is a breathtaking experience…” (Denby, 1942).

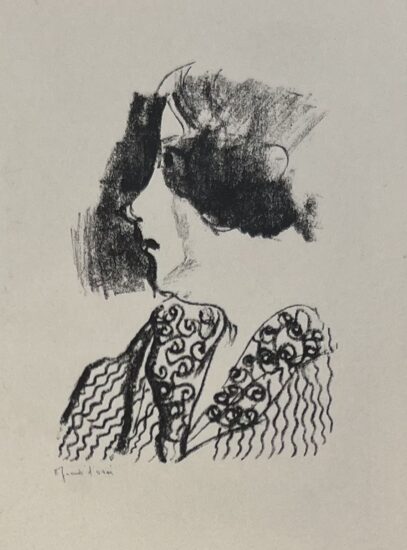

After only living in New York City for three years, the sudden death of his beloved wife and muse, Bella Chagall, in September 1944 left him devastated.

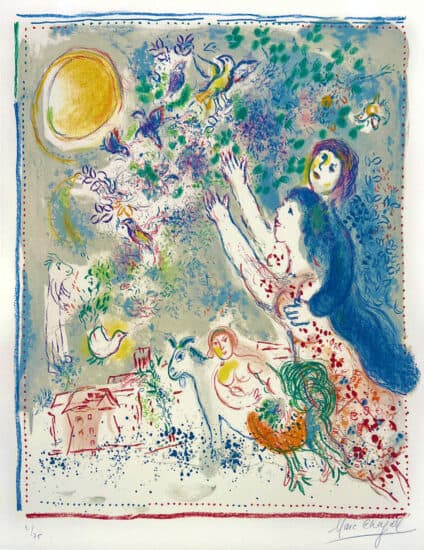

He stopped his work for many months, and upon resuming became concerned with preserving Bella’s memory and expressing his grief. In the works “The Wedding Candles” (1945) and “Self-Portrait with Clock” (1947) Chagall focuses on the emotions of longing and loss with hints of the beginning of a new love. There is a tension between the memory of Bella and the presence of his new love Virginia Haggard McNeil, which soon gives way to his artwork moving away from war and sadness to reflect the more familiar Chagall symbolism that expresses joy and love.

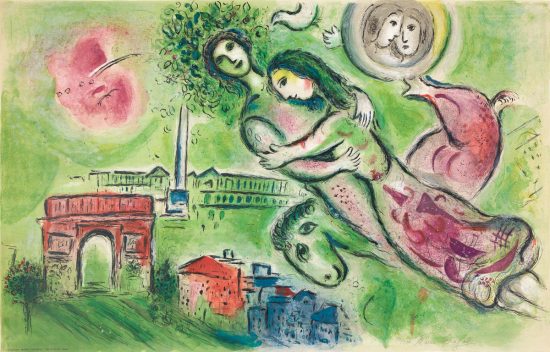

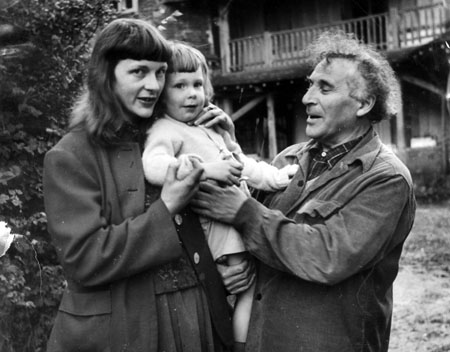

Chagall and Virginia move to High Falls, New York (http://www.highfallsnewyork.com/) in the mid-Hudson Valley in 1945 due to her pregnancy, which is when his art fully embraced love and familiarity, especially his early life in Vitebsk and Paris. Featuring distinct French backgrounds, “Bouquet with Flying Lovers” (1947) and “Lovers Near Bridge” (1948) both celebrate the beauty of lovers, while “Cow with Parasol” (1946) celebrates the beauty of birth. A hopeful time in Chagall’s life that he embraced with artistic fervor.

With the end of World War II, Chagall began making preparations to return to Paris, the city that he long considered home. As his artwork was becoming more widely recognized, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, gave him a retrospective in 1946, a touching tribute if there ever was one. He left New York in 1948, reflecting:

“I lived here in America during the inhuman war in which humanity deserted itself… I have seen the rhythm of life. I have seen America fighting with Allies… the wealth that she has distributed to bring relief to the people who had to suffer the consequences of the war… I like America and the Americans… people there are frank. It is a young country with the qualities and faults of youth. It is a delight to love people like that… Above all I am impressed by the greatness of this country and the freedom that it gives” (Baal-Teshuva, 170).

© Archives Marc et Ida Chagall, Paris. Photo courtesy of The Jewish Museum

During the remainder of his life, Chagall visited New York occasionally to work and even applied for an American visa twice, but was denied due to his political affiliations. The F.B.I actually kept a file on him detailing his pacifist or left-wing sympathies during his time in New York during WWII, which could account for the denials. Whatever the circumstances, Chagall never forgot the city that sheltered him during one of the most tumultuous times of his life. A time where he pursued multiple agendas simultaneously in art, making the world take notice and propelling him into further fame.

It is during Chagall’s time in New York and the influences of his experiences that his development as both an artist and person shaped him for the rest of his life. Making rich additions to his oeuvre that include not only glass, sculpture, lithographs, and tapestries but stage and costume design in addition to challenging the perception of what is acceptable to be portrayed. Chagall’s skill is certainly color and form, but it is his ability to create intimate fantasy’s with intricate storytelling that captivate his admires and those stories told during his time in exile in New York are some of his richest.

References:

- Denby, Edwin. New York Herald Tribune, Oct. 6, 1942.

- Baal-Teshuva, Jacob. Marc Chagall. Taschen: Koln, Germany, 1998.

- Marc Chagall Wikipedia

- Bella Chagall biography

Exhibitions:

- September 15, 2013 – February 2, 2014: “Chagall: Love, War, and Exile” at the Jewish Museum in New York.

– A look into Chagall’s oeuvre that explores his works before, during, and directly after World War II.

- 21 February 2013 – 21 July 2013: “Chagall: Entre Guerre et Paix (Between War and Peace)” at the The Musée du Luxembourg in Paris, France.

- 8 June 2013 – 6 October 2013: “Modern Master “ at Tate Modern’s Liverpool outpost in London, England.

– A presentation of artworks surrounding a young Chagall in the midst of WWI, the Bolshevik Revolution, and 1920s Paris.

- September 3, 2011- October 30, 2011: Chagall in High Falls at the D & H Canal Museum in High Falls, New York.

– Visually charts the famous émigré artist’s time in High Falls, New York.

Documentaries, movies, and popular culture:

Jewish Suffering | A Look at Jesus in Jewish Art Short Video

Books:

Harshav, Benjamin. Marc Chagall: The Lost Jewish World. Rizzoli, 2006

Bohm-Duchen, Monica. Chagall A&I (Art and Ideas). Phaidon Press, 1998.

Harshav, Benjamin. Marc Chagall: The Lost Jewish World. Rizzoli, 2006

Jewish Museum. Chagall: Love, War, and Exile. Yale University Press, 2013.Wilson, Jonathan. Marc Chagall (Jewish Encounters). Schocken, 2009.

Wullschlager, Jackie. Chagall: A Biography. Knopf, 2008.

Other works of art during this time period:

Marc Chagall, “The Fall of the Angel”, 1927-33-47. Oil on Canvas

Marc Chagall, “Hour between Wolf and Dog (Between Darkness and Light)”, 1938. Oil on Canvas

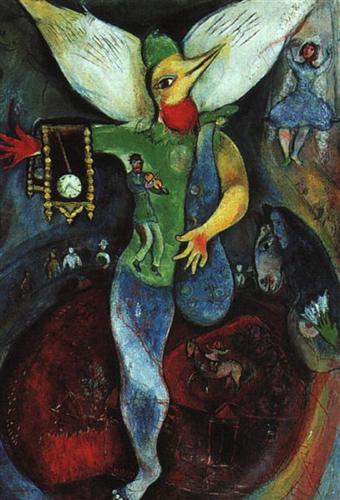

Marc Chagall, “The Juggler”, 1943. Oil on Canvas

Marc Chagall, “ Self-Portrait with Clock”, 1947. Oil on Canvas