Marc Chagall’s fascination with lithography came later in his life, as he was 63 years old when he began to study with printmaker Charles Sorlier in 1950. Sorlier became his creative collaborator and master printmaker, assisting him in the Mourlot atelier.

At this time, Chagall was already a famous artist, yet he worked hard to master the printmaking medium with the assistance of Charles Sorlier.

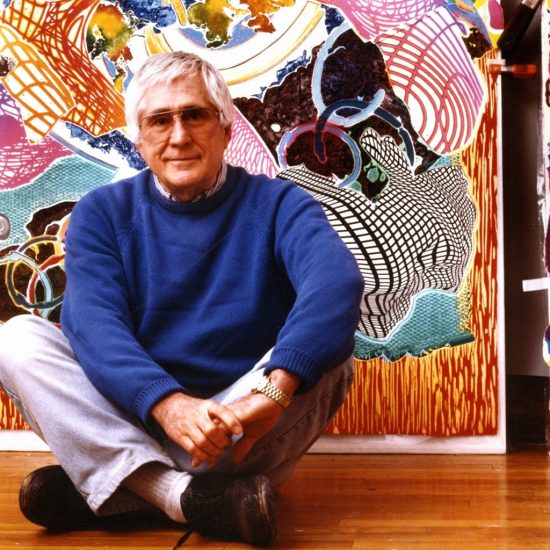

Charles Sorlier first entered Fernand Mourlot’s atelier in 1948 after being deported to Pomerania during World War II. He remained there for over 40 years, assisting many famous artists aside from Chagall such as Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Fernand Léger. However, his working relationship with Chagall was perhaps the most significant of his lifetime, as the two men were not only artistic collaborators but also great friends.

In working together to create Chagall’s original lithographs, Marc Chagall and Charles Sorlier developed a methodical procedure. Chagall would draw a composition in black on stone, zinc, or transfer paper, creating the general outline of the work. After printing a few proofs, Chagall would then add color in water color or pastel. Once he was satisfied, he would print the principal plate. Sorlier and Chagall would then conduct color tests, assuring that everything was in order. Chagall was a perfectionist, and he would revise and rework his pieces until they met his high standards. Sorlier’s role in this process was to touch up the plates and add color to Chagall’s specifications. This would save Chagall trips to the studio, as he trusted that his master printmaker could adjust his works to his liking. Sorlier would also evaluate the quality of the lithographs and the number of proofs. He would hand number the proofs allotted and destroy any leftover or excess proofs. Chagall would then hand sign these numbered lithographs.

Chagall and Sorlier were so close that Chagall gave Sorlier permission to engrave interpretive lithographs after his original paintings.

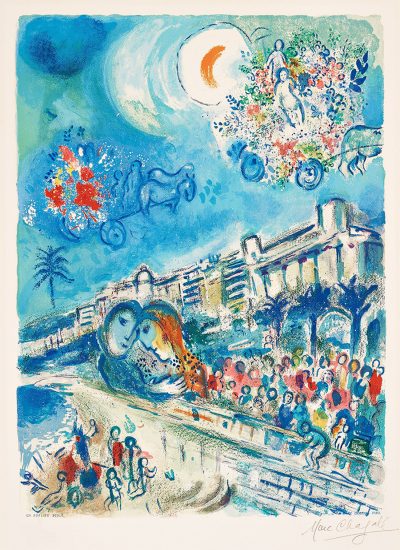

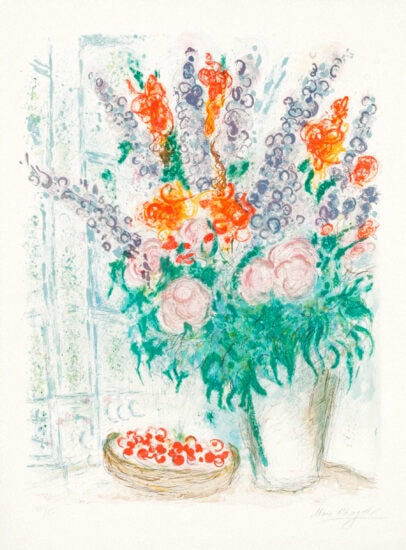

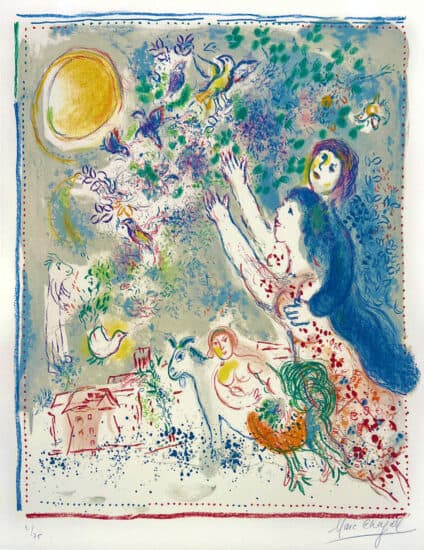

These so called afterworks are currently some of the most valuable and sought after works of Chagall’s entire artistic oeuvre. With its monumental size and vivid blue and yellow coloring, The Magic Flute (1967) is considered one of Chagall’s most desirable original color lithographs of all time, while works such as the Tribe of Naphtali (1964) and Tribe of Zebulun (1964) created after Chagall’s twelve stained glass windows for Jerusalem and Avenue de la Victoire at Nice (1967) and Roses et Mimosa (1967) from Nice and the Côte d’Azur also stand out with their symbolic and whimsical imagery. From Red Poppies (1949) and The Champs-Elysées (1954) to Bonjour Paris (1972) and Angel with Candlestick (1973), these magnificent color lithographs speak for themselves concerning the skill and energy devoted to their creation by both Sorlier and Chagall.

Sorlier would use a picture or gouache by Chagall as a starting point for these lithographs, creating trial proofs for the print. He would then submit these trial proofs to Chagall, who would go over them in gouache or pastel. Chagall was extremely devoted to the process, constantly touching up these works. Sorlier states:

It is in this way, to the surprise of certain publishers, that a plate begun in six colors can comprise twenty-five in its definitive version. The result so obtained is in fact a new creation, and not a reproduction, having but a very distant relationship with the initial maquette. Indeed, Chagall reworks these compositions so extensively that they can almost be considered as original engravings. However, the great integrity he invests in his work prevents him from making such a denomination. He requires that the plate bear my name each time he has not directly participated in the transcription to stone (Sorlier, pg. 13).

These afterworks are the astounding results of a fruitful and harmonious collaboration between Chagall and Sorlier. Chagall, ever the modest artist, was set on giving credit to his good friend and master printmaker Charles Sorlier, a man that he greatly admired. For this reason (as Sorlier states above) most of these afterworks are not only hand signed by Marc Chagall but also signed in the stone by Charles Sorlier.

Chagall and Sorlier were so close that Sorlier was one of the last people to visit Chagall before his death.

Through their united vision and amiable relationship, these two gifted artists changed the face of printmaking, creating original lithographs that to this very day inspire awe and spark the imaginations of viewers worldwide.

References:

- Sorlier, Charles. Chagall Lithographs Volume 5 (1974-1979). New York: Crown Publishers Inc., 1984.

- Charles Sorlier biography

Browse the entire Marc Chagall Catalogue Raisonné.