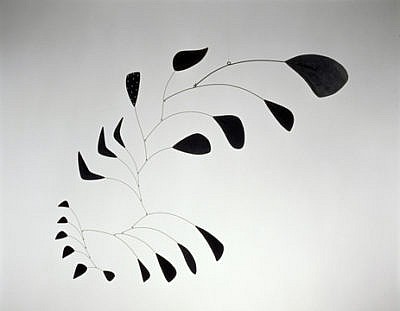

Alexander Calder mobiles take a magnificent place in the history of Modern Art. What we now see hanging above the beds of toddlers, entrancing young children everywhere, started as an avant-garde art undertaking.

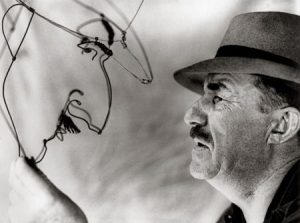

Alexander Calder was raised by a sculptor father and painter mother. He attended school for Mechanical Engineering before finally becoming a full-time artist. Both his personal and educational backgrounds set him up for his foray into kinetic sculpture. His father, Alexander Stirling Calder, was a well-known sculptor who created many public installations, and Calder’s grandfather, sculptor Alexander Milne Calder is best-known for the colossal statue of William Penn on top of Philadelphia’s City Hall tower. It’s no wonder that Alexander Calder, being surrounded by such creativity from a young age, would be most famous for designing a new art medium through three-dimensional creations.

Throughout his childhood, Calder was always constructing toys. He was fascinated with using objects to create multiple dimensions, and upon receiving his degree in mechanical engineering in 1919, Calder decided to apply his passion and formal training to a career as a professional artist. He attended art classes in New York, and in 1926 moved to Paris, where he received acclaim for putting on small-scale circus performances known as Cirque Calder. Calder created a series of metal figures that would move around a circus tent. He performed the show for small groups of friends with his wife, Louisa. The Calder Cirque is now at the Whitney in New York City.

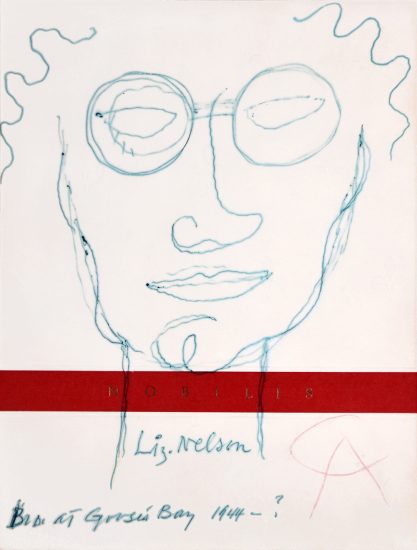

The term ‘mobile’ was given by Marcel Duchamp. Alexander Calder on his mobiles in 1943:

A mobile in motion leaves an invisible wake behind it, or rather, each element leaves an individual wake behind its individual self … In setting them in motion by a touch of the hand, consideration should be had for the direction in which the object is designed to move, and for the inertia of the mass involved. A slow gentle impulse, as though one were moving a barge, is almost infallible. In any case, gentle is the word.

Alexander Calder, unpublished in his lifetime, about art in motion. [0]

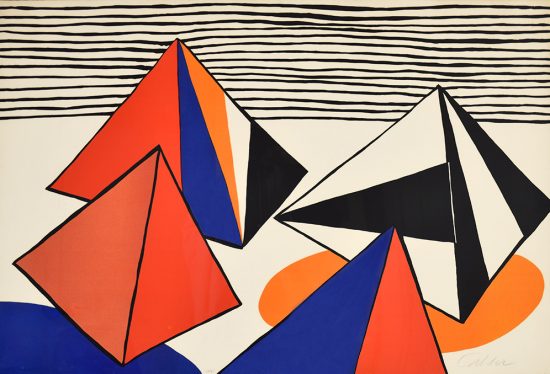

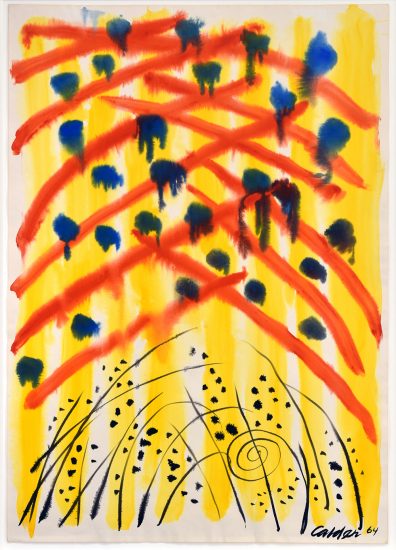

Through the creation of the Cirque Calder, Calder’s interest in both wire sculpture and kinetic art began. He maintained a sharp eye with respect to the engineering balance of the sculptures and utilized these to develop the kinetic sculptures. Calder’s further experiments to develop purely abstract sculpture came from his visit to Mondrian’s gallery where Calder was inspired to make art multidimensional. This lead to his first truly kinetic sculptures, manipulated by means of cranks and pulleys. By suspending the works in mid-air, Calder discovered that he could add life to the otherwise static sculpture.

Alexander Calder's mobiles were driven by an electric motor which allowed for more precise motion and movement, instead of being at the mercy of the wind. About his non-motorized mobiles, Calder explained that difficulty that “all of them react to the wind, and are like a sailing vessel in that they react best to one kind of breeze.”

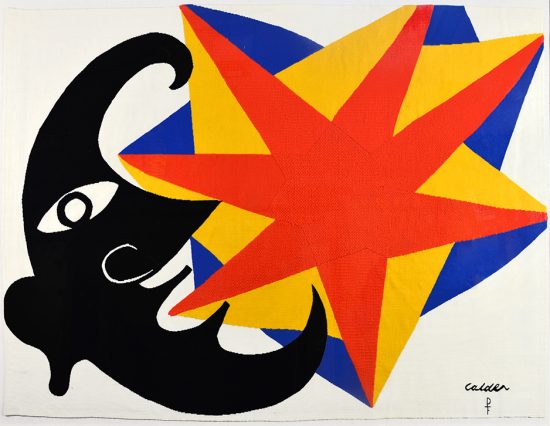

Calder’s mobiles are spectacular for many reasons, one of which is that they are created to interact with the world around them – a type of art that Calder was one the forefront of exploring. The hanging mobiles are altered by air and touch, allowing for a dynamic expression in space. Calder also created standing mobiles, which were placed on the ground but still had interactive hanging components.

Calder is noted as saying, “Out of different masses, tight, heavy, middling—indicated by variations of size or color—directional line—vectors which represent speeds, velocities, accelerations, forces, etc. . . .—these directions making between them meaningful angles, and senses, together defining one big conclusion or many.” From this, we can only glimpse at the magical vision he had of the world that surrounded him. The mobiles and stabiles he created to encapsulate that vision continues to inspire us to see the intertwining relationship of all the elements in the universe.

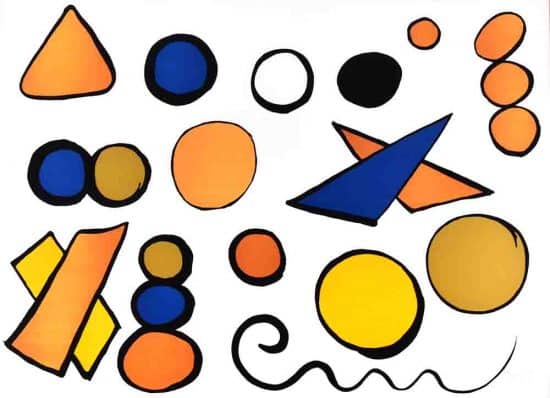

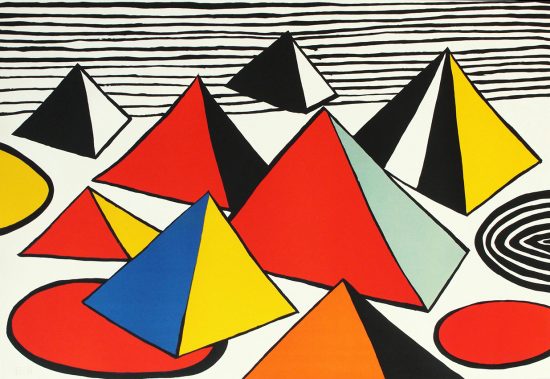

View our collection of Calder drawings.

References

0. Alexander Calder’s statement, unpublished in his lifetime, about the gentle impulse of his art in motion. https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/518

“Alexander Calder.” SF MoMA. Accessed January 30, 2017. https://www.sfmoma.org/artist/Alexander_Calder/

Calder, Alexander. ‘Mobiles’ in The Painter’s Object, ed. Myfanwy Evans, 62-67. London: Gerold Howe, 1937.

Calder Foundation. Accessed January 30, 2017. http://www.calder.org/

Hall, James. “Magnificent mobiles: the art of Alexander Calder.” The Guardian. October 23rd, 2015. Accessed January 30, 2017. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/oct/23/alexander-calder-sculpture-fine-balance

Mitgang, Herbert. “Alexander Calder at 75: adventures of a free man.” Art News. December 19th, 2015. Accessed January 30, 2017. http://www.artnews.com/2015/12/19/retrospective-calder-1973/

Pritchard, Claudia. “Alexander Calder: The mechanical engineer and his pioneering mobiles.” The Independent. November 1st, 2015. Accessed January 30, 2017. http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/art/features/alexander-calder-the-mechanical-engineer-and-his-pioneering-mobiles-a6715456.html