Fine Art & Maternity:

Humanity has engaged in maternal celebrations since the dawn of civilizations, and has been a universal event that all have somewhat of a relationship with. Maternity is celebrated by holding parties, gatherings, grand announcements, and having art commissioned with the mother and future child front and center particularly if the family is well-off. Capturing motherhood within artistic mediums has remained an intimate bond among lovers, husbands, and eventually artists themselves when reflecting upon their own maternal experiences no matter the social status of the subject. Maternite has transformed from motherhood being the subject to view into a concept that the mother herself reflects upon as herself instead of an outsider looking onto a stranger in a staged setting.

Of course, the mother is only half of the picture. Celebrating the birth of a child through painting, sculpture, and other mediums has been a long standing tradition of families to celebrate their exuberant joy of beloved family additions. However these traditions have been portrayed, the truth of our society is our penchant to disregard the traditions of the past, to rebel against the social norms we hold so dear, until we come out on the other side of the pendulum of fads and trends to create new ideals in all of our world. It is an obvious change in emotion-driven mother and child portraiture in the past years.

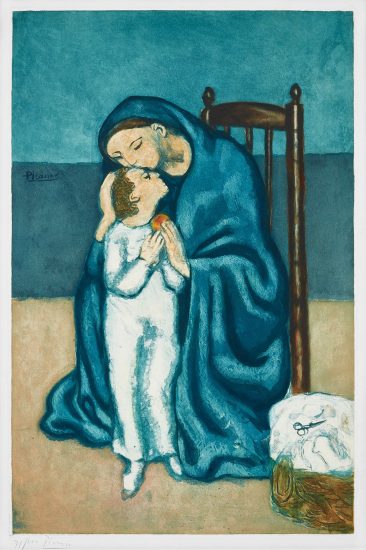

When we study the trends of the past we often see ourselves in our predecessors. However the ideals of royal families of the past may have announced and immortalized the birth of a child, in the 20th century there is more intimacy, more tenderness than shown in previous family portraits. There can also be less positive emotions attached to the birth of a child. The gentleness is not lost with a subject such as Madonna and Child, but there is always an underlying current of foreboding in such a subject. A common theme in many if not all maternity portraits is to be a copy of a copy of the Holy Family, though with considerably less memento mori entangled within background characters.

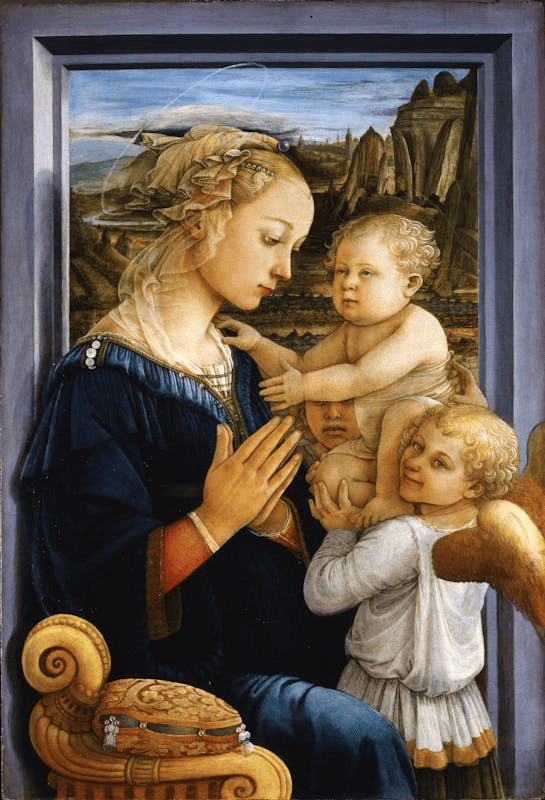

Madonna and Child with Two Angels, painted by the influential Phillipo Lippi, has been redone and reanalyzed through the ages because of its strong maternal display of affection. Mother Mary holds her sweet child Jesus while looking happy and sad at the same time. Duality of emotions in the mother are coerced by the reminder of death. The stage is set, and Sybil-like warnings of the young Christ Child's future are evident in the knowing look of the two angels supporting the babe, even if one is partially hidden. (Uffizi) It is among the most popular Madonna and Child portraits that have inspired mothers from all ages to have their own portraits of their beloved children.

Madonna and Child with Two Angels, Filippo Lippi (Florence 1460-1465)

Melancholy Mary has her clasped hands poised for prayer as if readying herself for the worst while her infantile son holds her gaze, all-knowing and prepared for his future. The scene, although more than a simple duo, has a background composed of cliffs, fields, valleys, and of course far off towers indicating his time as ruler of the Christian world will someday come to pass. Another indicator of royalty is the Virgin Mary’s luscious golden throne, just visible on the bottom left as though not to impose upon the other members of the tableau. (Uffizi) The image has obvious notes of Catholic Papal propaganda, but it cannot be denied that it is beautifully executed. Precedents suggest that this is a loving, tender scene, but a closer look unveils all warnings discussed previously, and it can presumably be agreed that there can be much more to a scene than a simple mother-and-child portrait.

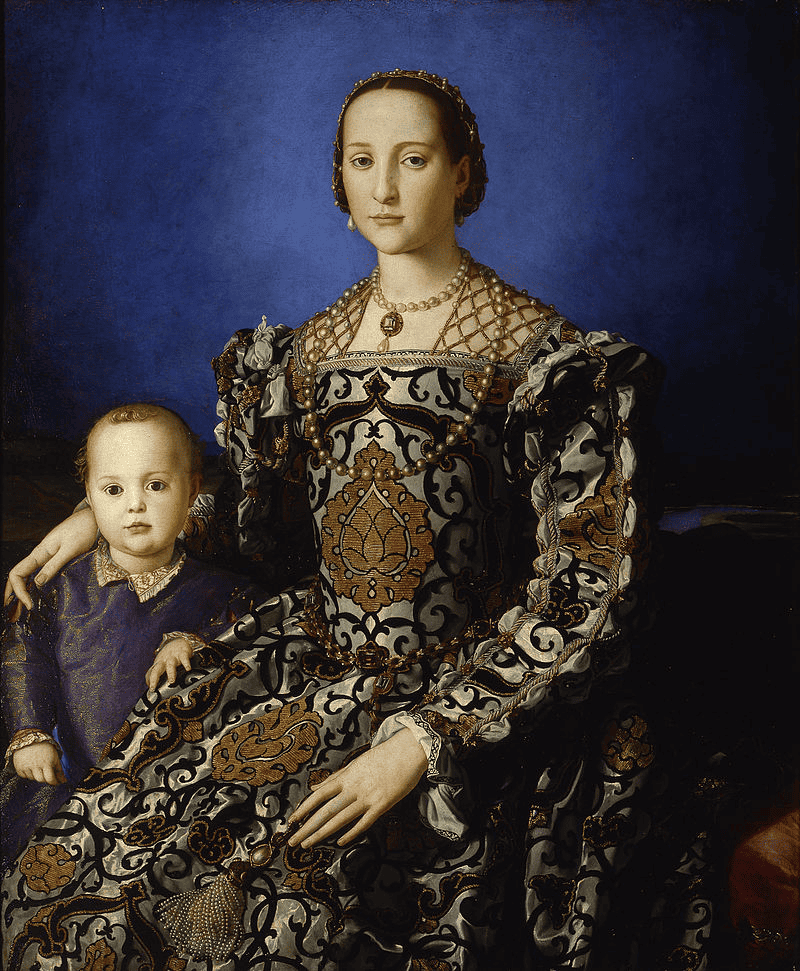

Eleanora of Toledo, a fabulously rich mother, had the portrait of her young son painted by the talented Bronzino, a master painter of the Mannerism style. Bronzino was dedicated to this distinct style when he painted this stunning portrait “which reveals his love of complex symbolism, contrived poses, and clear, brilliant colors.”(Britannica) Mannerism, occurring between the High Renaissance and the Baroque Era, has a distinct clarity of color and cut in shape and style. The aforementioned painting contains all of the unique characteristics of the Italian Mannerist movement, and remains clean with its wintery tones and facial expressions depicted in the mother.

The wealth of this family can be seen in the ostentatious brocade of Eleanora’s dress. The fabric was, in fact, so expensive to make that the dress itself is non-existent, and the dress pattern was fabricated after a piece of the costly embroidery by the artists. (Uffizi) Having such a costly garment was a show of wealth and power that the medici family desperately needed to show off in order to retain their power. This portrait has the effect of a proud but demure mother humbly bragging of her power and money with her soon-to-be influential young son being showcased for all to see. Portraits of this kind are used for political power while barely attempting not to come off as egregious.

Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo and Her Son, Bronzino. 1545

Elegance in this instance, despite being an intimate portrait of mother and son, was imperative. Eleonora was a very powerful woman in Florence, Italy during the reign of her family the Medicis, so it of course follows that her portrait with her young son has a very brooding, official appearance when in comparison to previous and future mother and child duos. The colors are crisp, the lines crisp, and her child attentive rather than slobbering, napping, or running amuck. The portrait holds symbolic intricacies that tie her baby to his presumed future as pope, the reason he was deemed fit enough to appear in an official portrait in the first place. (Uffizi)

In the Renaissance, somewhat like today's maternity photoshoots, a first look at the mother and child post-birth is a privilege to the every-day viewer. Showing health and prosperity, as well as strengthening the hold of the family’s grasp on Italian politics, was the driving factor of Eleanora and Giovanni’s frigid portrait. However, maternity pictures have changed with the times. Warmth and love are shown later in history in times when paintings become a more accessible art practice.

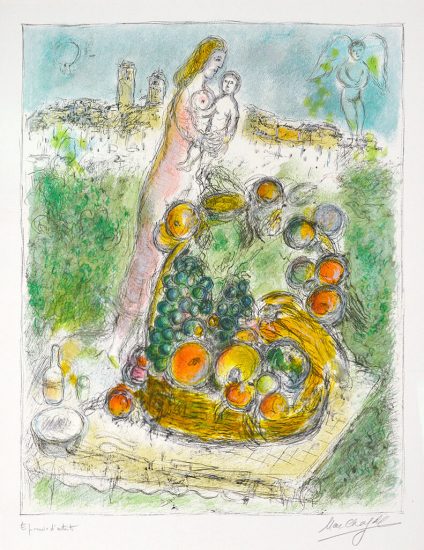

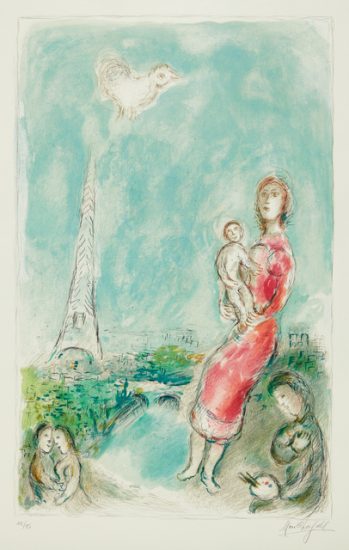

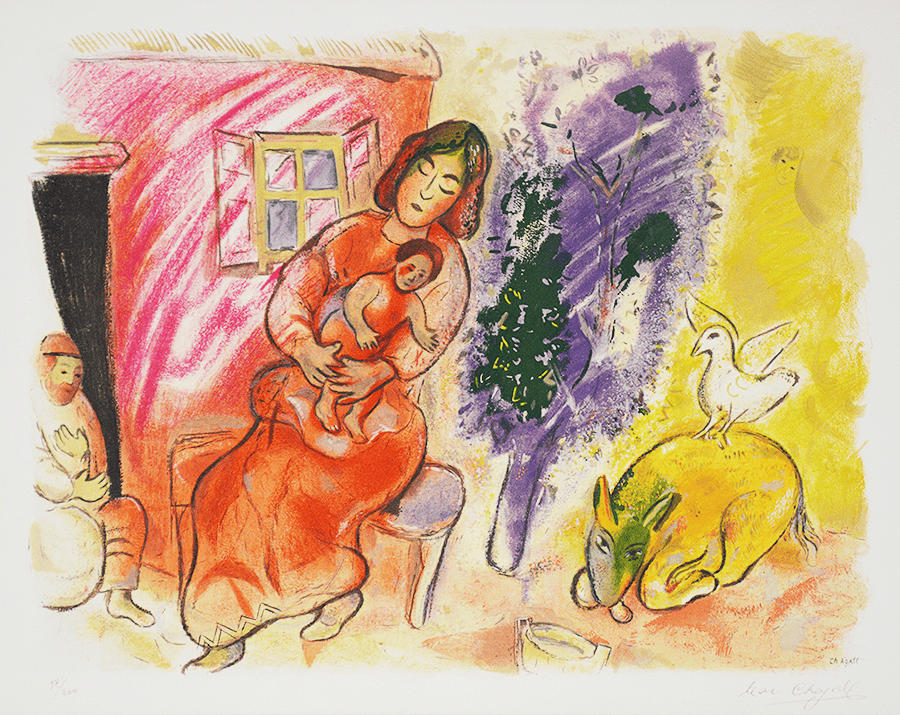

On another note of historical point of view besides propaganda and coldness, Maternité by the artist esteemed Marc Chagall has won over many hearts by portraying a scene out of a pleasant picture book. A loving home full of warmth and brightness surrounds the caring mother and curious child held loosely within her arms. This lithograph contains energetic and bright colors throughout the background and swarms the viewer with a cozy, intimate scene. Rather than a political piece lobbying propaganda throughout a chosen region, Chagall paints a dreamscape that offers the viewer a glimpse of harmony between a humble mother and child.

By combining textures, Chagall creates more depth in the backdrop than would be possible in flat pigment. Thrashing motions of eggplant purple lend a more structured, deeper depiction to the tree beside the cuddling mother. Opposite, sunshine-yellow is cloudy and smudged, perfectly challenging the sharpness of the neighboring foliage. All the brightness is a direct contrast to the more formal, regal colors of the more traditional paintings seen.

The dove, traditionally signifying peace and love, looks upon the mother and child duo. It is also possible that it is the object of the toddler’s singular attentiveness. A mysterious male figure crouches to the right of the small family, and is more of a background character in this setting. On the far left, barely perceptible in the yellow haze, the faint tracing of an animal can be seen watching the familial tableau. Casual ease permeates the entirety of the scene, lulling the viewer into a sense of security within the mothers benevolent gaze. Chagall looks upon the mother and child as if they are a perfect reflection of what a loving mother should be, giving up his position as an outsider to their world.

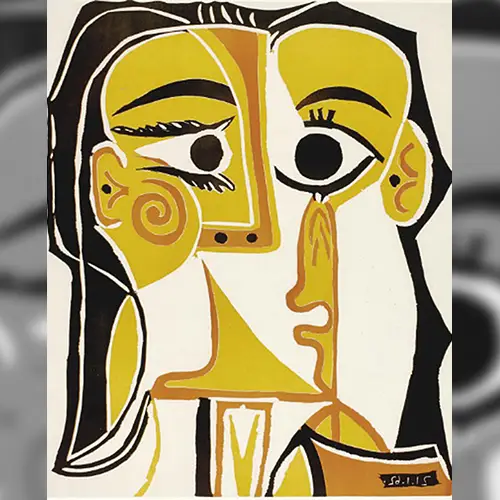

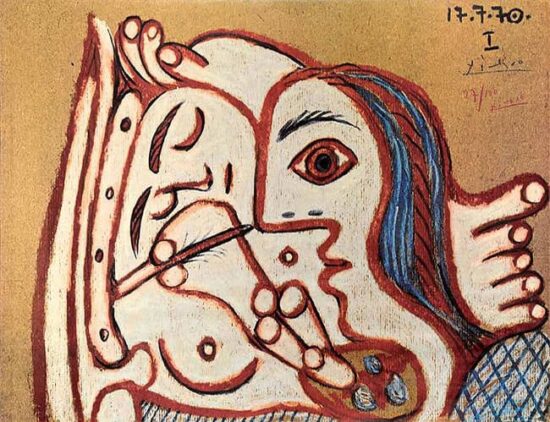

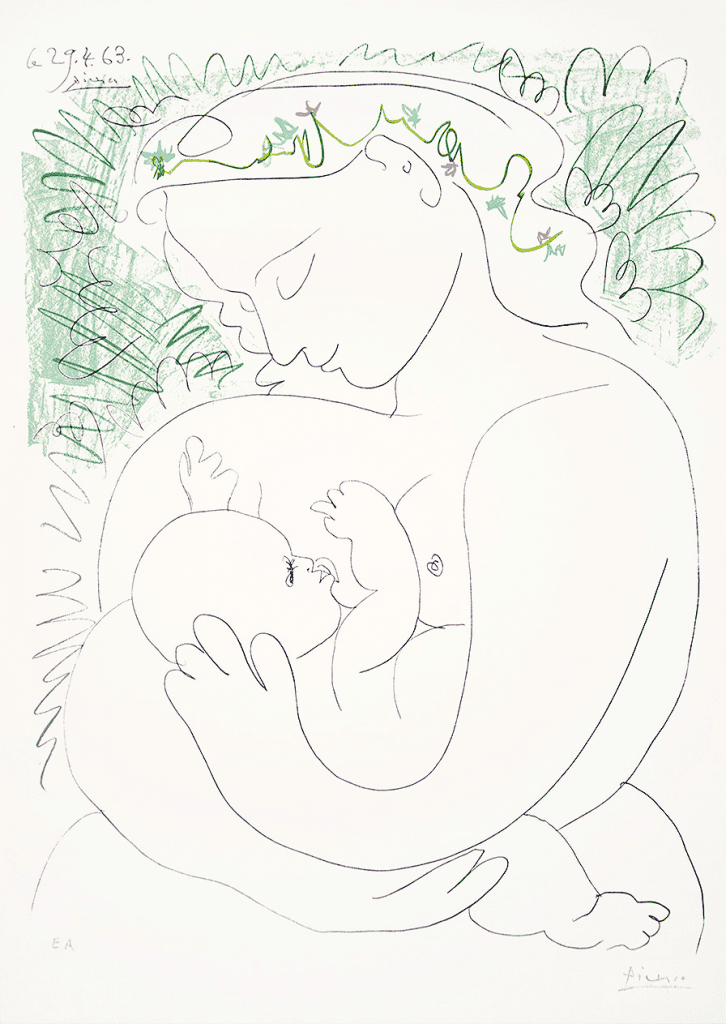

Pablo Picasso, Grande Maternité, 1963

Maternal instinct is perhaps one of the most powerful forces in the world, whether animal or human. For humanity, motherhood can be very beautiful and sweet, or scary and protective. In many paintings and works of fine art, we see the sweeter side of the story. In Picasso’s Grande Maternite, this is exhibited nicely. The lightness of the colors, a simple spring green and little printemps flowers lend all the color we need to feel the delicate emotions of the mother cradling her child.

A flower crown adorns the mother as if channeling the likeness of the Greek goddess Demeter holding her daughter Persephone. Picasso incorporates the ideas that Demeter is known for, namely fertility. Upwards of the floral wreath, the brightness of the green alludes to fertility and the ability to bear a healthy, happy child, Even though the lithograph is simplistic, it conveys all the tenderness of the mother tending to her beloved child. All of the lines are soft and curvaceous, nothing too sharp or angular to contribute tension to the delightful duo therein. Idealistic views of the mother and child, living and warm, shine throughout the piece.

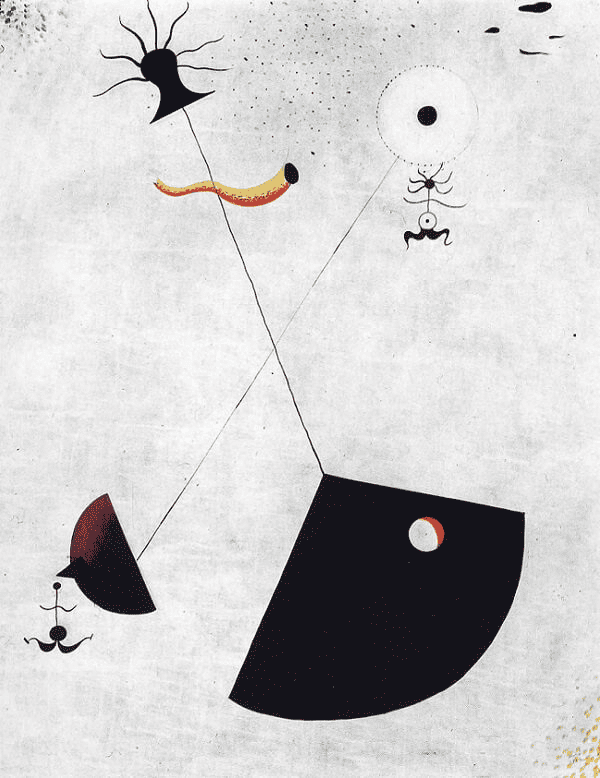

Mothers are, more often than not, seen cradling, nursing, or consoling their children in one way or another when depicted in fine art. Nursing is, of course, often the symbol that is used to announce the presence of a mother in art. Miró, known for her picture puzzles style paintings, has deconstructed the ideas of a mother to hips, breasts, and children. Two children are seen hanging onto the mother figure by the teet. The male child is distinguished on the left by his bald head, while the female child on the right had six long waves of “hair” to show her femininity. The mother herself has these waves sticking out of the top of what can be distinguished as her head, no doubt passing the dominant trait to her daughter. All the features of the family are rather simple, boldly contrasted shapes. The mothers breasts are shown in multiple angles, one straightforward and white, presumably exposed to some light source, and the other is a shadowed red, piercing through the white mass in its background.

Joan Miró’s dual vision on the subject of maternity is clear in her use of the breasts as opposing forces on either side of the painting, and far from the core of the mother figure. Rather than a formal portrait meant to be seen as a powerful future, Miró uses the children as extensions of the mother, but not for political or religious power. The children are simply there as subject matter. Mother and child are a concept instead of a reality in the painting. No emotion is conveyed by the nursing mother, but it seems as though her two children are generally sucking the life out of her as if they are two loveless leeches instead of two beloved children. Sans positive connotation, but still a testament to the ideals of Maternité.

Maternity in fine art has had a grip on society since societal norms came into existence. Throughout the centuries, we observe the change and affliction of time against rigidity, tradition, and formal portraiture. In Miro, Chagall, and Picasso there is a liveliness that became prevalent in the last century while Bronino and Lippi play into the formality of the society they catered to. Mother and child are seen as relatives rather than distant figures, challenging the vision of maternité in social settings, caste, and everyday variations in human society. Conclusively, when we compare paintings of similar subjects across the course of a few centuries, we may deduce the societal changes within our world with picture proof as evidence of the ever-changing world where art and motherhood combine. Mothers everywhere can breathe a sigh of relief as the art world changes in their favor.

bib.

Thomas, Joe A. (1994). "Fabric and Dress in Bronzino's Portrait of Eleanor of Toledo and Son Giovanni". Zeitschrift fürKunstgeschichte.om/biography/Il-Bronzino#/media/1/81135/219747

Texas A&M University. The Online Picasso Project. www.picasso.tamu.edu. Catalogue raisonné no. OPP. 63:311.

"Eleanor of Toledo with Her Son Giovanni". Britannica. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

Parenti, Daniela. “Madonna with Child and Two Angels by Filippo Lippi: Artworks: Uffizi Galleries.” Madonna with Child and Two Angels by Filippo Lippi https://www.uffizi.it/en/artworks/lippi-madonna-and-child-with-two-angels#online_exhibitions.

Browse our collection of fine art Pablo Picasso Maternity.

Browse our collection of fine art Marc Chagall Maternity.

Browse our collection of fine art Joan Miró Maternity.