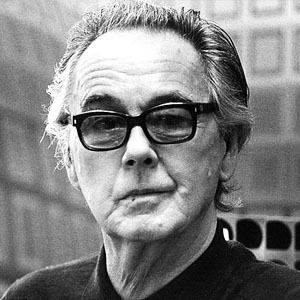

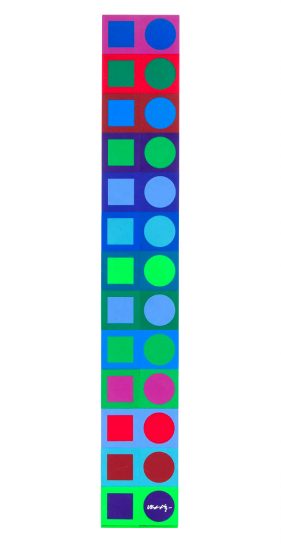

The following is a translated excerpt from the article, “The Vasarely Affair”.

Featured in the February 2010 issue of L’Objet d’art magazine, this article was written by Monsieur François Duret-Robert, veteran art-world journalist, professor, specialist in art-world jurisprudence and expert on droit moral.

It’s a family quarrel, but one that could deeply impact the image of Victor Vasarely’s works, whose origins stem from the variations of the artists’ moods. The court has had to decide if the artist himself was aware of his actions at the end of his life, when he decided to give his confidence in the future of his works to one heir, and then later granted the same to another. The situation was brought in front of the courts, whose first solution was to give the artist’s grandson reason.

To understand this dark story, we have to better understand the Vasarely’s. Victor Vasarely had two sons, André, a doctor, and Jean-Pierre, a brilliant artist known as Yvaral. Jean-Pierre had a son, Pierre, from his first marriage. Jean-Pierre then remarried Michèle Taburno, leaving her widowed in August 2002.

The current conflict between Pierre and Michèle concerns the droit moral for the Victor Vasarely works, a right that would have been willed to his son, Jean-Pierre and then to his grandson, Pierre.

The wills are different.

In his will, dated November 28th, 1990, Victor Vasarely states “my son Jean-Pierre, artist who has complete knowledge of my works to be the unique legatee of the moral right related to my work”. In a second will from the artist dated July 29th, 1991, the artist confirms exactly the same, but in a third will dated April 11th, 1993, he changes his will stating, “I give Pierre Vasarely my only grandson, the disposable part. He is the only one with the capacity to ensure continuation of my work at the Vasarely Foundation, which bears my name.”

The problem, in effect, is knowing if Victor Vasarely had all of his mental faculties intact when he drafted that third will. Dr. Patrick Fremont, the psychiatrist who examined the artist a few months later (January 1994) wrote that the artist was plagued by a disease that had obliterated him of his mental faculties and crippled his ability to express his desires. He went on to say that the artist suffered from “an intellectual deterioration which not only affected his memory, but did not afford him the mental capacity to make any decisions”. Then there’s the court appointed expert, Dr. François Régis Cousin, who expressed a significantly different opinion. During his testimony in June 1999, more than two years after the death of Victor Vasarely, Dr Cousin stated that “there was no reason to doubt the artists’ mental capacity on April 11th, 1993”.

Based on that expert witness’ testimony, on March 24th, 2005, the Paris court decided that “although Victor Vasarely suffered some weakening of the spirit as a result of his advanced age and mental disease, there is no evidence to prove a state of insanity on April of 1993, nor any reason to annul the will written on that date”. Therefore, we cannot contest the validity of the last will from a legal standpoint.

Who holds the moral right?

After Victor Vasarely and his son’s Yvaral’s death, two of their heirs claimed to hold the moral right for the Vasarely works, his daughter-in-law, Michèle and his grandson, Pierre.

Michèle invokes her husband, Yvaral’s will, which states, “I give my wife the moral rights to my work and to my father, Victor Vasarely’s work, which he willed unto me.” Pierre on the other hand, was claiming that the artist’s last will gave him “the disposable part”, which includes the moral right.

The Aix en Provence court decided that the last will was the one that would be accepted, as a result of that decision, Pierre is currently the titleholder for the moral rights to his grandfather’ works. More surprisingly, was the court’s order concerning the archives.

The destiny of the archives

The Aix en Provence court ordered Michèle to transfer Victor Vasarely’s archives to Pierre. A decision like this is highly suspicious, because the indisputable fact is that Victor Vasarely himself gave Michèle his archives; there is no doubt about this.

There is the artist’s letter dated August 8, 1991, where he wrote, “to the little Michèle, I give you my archives, my folders with the condition that you will always keep them and work together with Yvaral to protect my work”. Then, there’s the fact that in 2007, Pierre stated that Michèle has been in possession of the archives for 15 years, confirming that she received the archives in 1992, making it a “manual gift”, which by law means that there exists a consensual agreement between both parties. There is generally no way to reverse a “manual gift”. Therefore it is very surprising that the judges did not take this evidence into consideration, and even more surprising how the court explained their decision, stating that “the archives are indispensible and correlate to the moral right.” That concept is incredibly difficult to defend.

Let’s pose the question clearly: what are artist’s archives for? The response is rather evident: to certify the authenticity of their paintings and drawings in addition to establishing the catalogue raisonné. Having the moral right does not include any prerogative on either certifying authenticity of the cataloguing of the works. We all know that there exists a lot of confusion about this in the artworld, and many people confuse the moral right and the ability to certify the authenticity of the works, but there is an abundant amount of jurisprudence that support the fact that these functions are not one in the same.

The Paris court said that “the prerogatives of the moral rights, which belongs to the heirs, is simply to protect the image of the artists, since the knowledge they purport to have about the artists’ creations does not give them any power on authenticity.”

When you look at all the different judgments and court decisions regarding moral rights, the very limited credit the courts give the artist’s heirs is stunning. Additionally, the certificates of authenticity created by the owner of the moral rights carry little weight in the courts eyes. As for the realization of the catalogue raisonné, there is no implication that this privilege belongs to the artists’ heir. The completion of a catalogue raisonné, the scientific classification of the artist’s works, can belong to anyone. The only necessity is to respect the copyright obligations associated with the works.

Returning to the Vasarely affair, the question now is who will be recognized as the specialist for the artist’s work? The answer is simple: the person (he or she) that proves they are the most knowledgeable in the artists’ works. Whether or not they hold the title to the moral rights is not important, and justly so.