In July of 1946, Pablo Picasso traveled to a small town in the South of France, known for its ceramics and pottery, called Vallauris. His first trip there would spark an interest in the field of ceramics for Picasso that would go on for many years, and come to define the latter years of his career. On that trip Picasso came across a Madoura Atelier pottery stand, and was intrigued by the quality of their work. The atelier was owned by Suzanne and George Ramie, who would later invite Picasso to experiment with his ceramics in a corner of their studio.

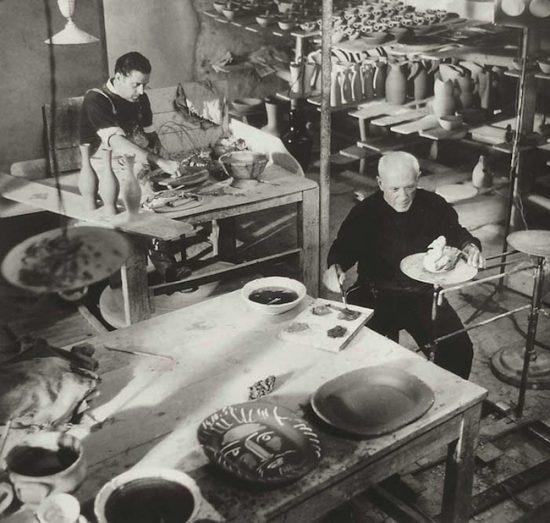

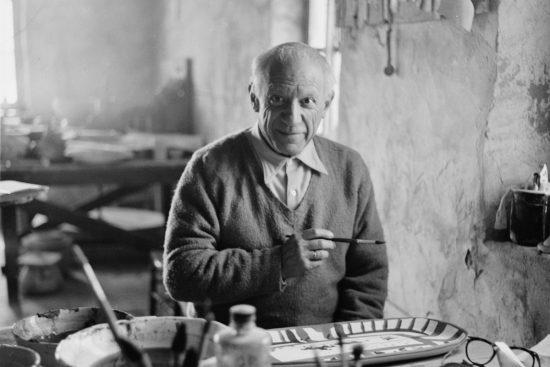

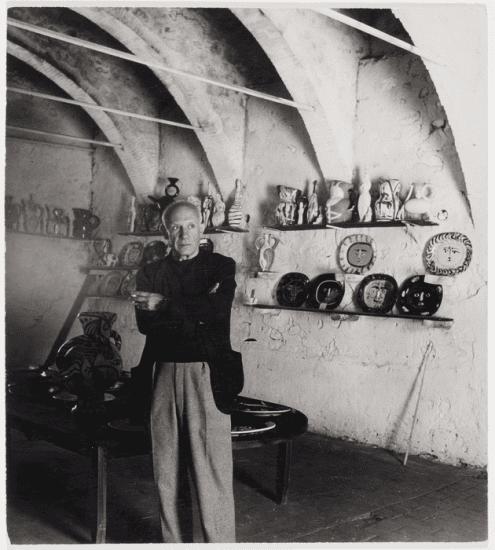

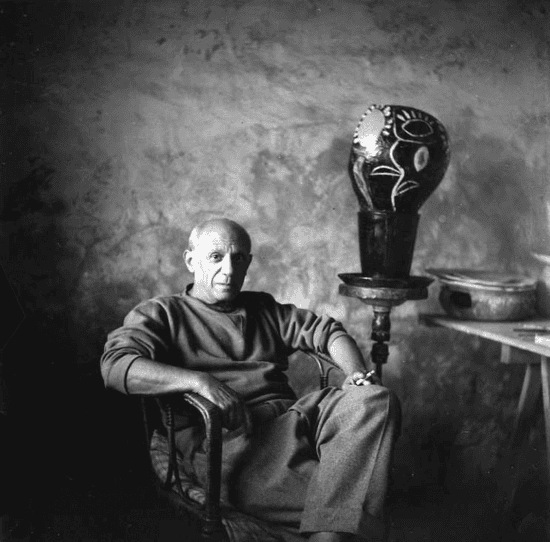

When Picasso began making his beloved Picasso ceramics sculptures, he was in his sixties. He had long since been an established and well-known artist, due to his incredible mastery in painting, sculpture, drawing and print-making. Picasso was constantly experimenting in those mediums and it makes sense that he wanted to delve into the world of ceramics as well. He was a lifelong student of art techniques, and pottery was something he had zero knowledge of up until this point in his life. Claude Picasso, one of his sons, said of his pottery, “My father never considered himself a potter. But approached the medium of clay as he would any other in order to find out what the materials and techniques of the potter’s studio could offer him and what he could discover by probing their inherent qualities or possibilities.” Picasso used his time with the Ramies to learn everything he could about pottery techniques. He made Vallauris his residence from 1948 to 1955, and experimented during this time with ceramics with the help of pottery expert, Suzanne Ramie.

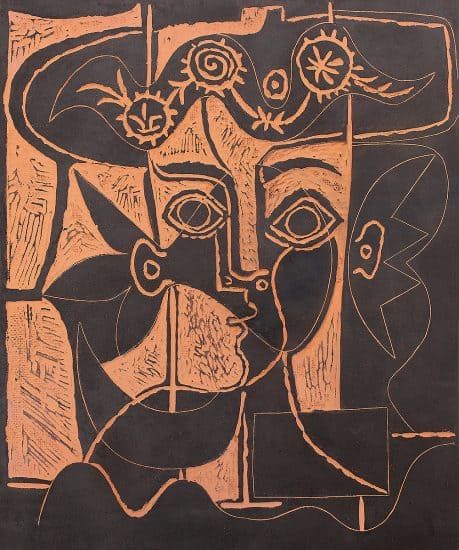

Picasso’s ceramic experiments included pitchers, plates, vases and plaques that he hand-crafted, fired and painted. He worked from sketches he would bring into the pottery studio, and there he began translating his two-dimensional ideas into three-dimensional creations. He often experienced structural issues and problems with his decorative elements, and spent long hours trying to correct his technique through trial and error. Though he lacked in technical knowledge, he made up for it in passionate determination.

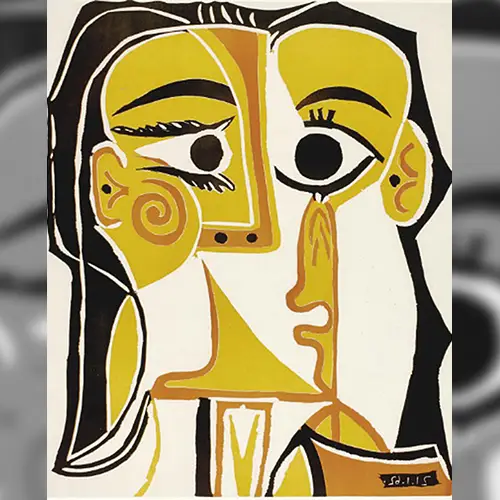

Some of Picasso’s ceramics, like Tête (Head), 1956, are painted with delicately colored glazes. Mastering glazes like these takes many years of practice and skill, since the artist can’t be sure how the firing of the kiln will affect their design. There are many different factors that can affect the outcome of the piece in the kiln. High temperatures, the makeup of the glaze and the type of clay used can all change how the firing process goes. Creating subtle variances in his pigmented glazes is extremely difficult to perfect, and many of his works would have ended in disaster before reaching any sort of consistency. Picasso did not believe any ceramics should be thrown away, so even when his pieces cracked or broke in the kiln, he had Madoura artisans work as his “mechanics” and patch up the ceramic as best they could.

Picasso's experimentation with pottery changed the medium as a whole. Creating new ways of decorating and glazing his three-dimensional works allowed Picasso to express his artistic ideas in ways that had never been done before. Picasso’s ceramics are a large and influential portion of his life’s work and it is fascinating to see his progress from ceramic novice to pottery prodigy.

Please view our vast fine art collection of Pablo Picasso ceramics for sale.

Curious Insight: Picasso and the Madoura Ceramic Studio: A Transformative Artistic Journey