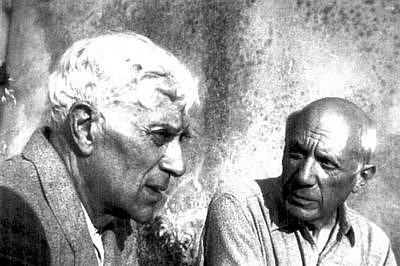

In the spring of 1907, Georges Braque visited the studio of Pablo Picasso to view Picasso’s notorious work Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). Impressed with what he saw, Braque quickly befriended Picasso. In the years that followed (1907-1914), Picasso and Braque were essentially inseparable. As Braque recalled, “We were like mountain-climbers roped together.” The two artists worked so closely together that their works from this period are sometimes difficult to tell apart.

Picasso and Braque forged a relationship that was part intimate friendship, part rivalry, and part two-man excursion into the unknown. The two artists were constantly in each other’s studio, scrutinizing each other’s work while challenging, motivating, and encouraging each other. Picasso said, “Almost every evening, either I went to Braque’s studio or Braque came to mine. Each of us had to see what the other had done during the day.” Through this artistic collaboration, Picasso and Braque invented Cubism, a new style of painting that shattered traditional forms of artistic representation.

Picasso and Braque’s relationship epitomizes the attraction of opposites. Braque’s father was a house painter and decorator who ensured that his son learned the necessary skills of his trade, while Picasso’s father was an academic painter who gave his son professional drawing lessons. Braque was a tall, reserved, systematic Frenchman whose artistic process was dictated by reason and balance. An incredibly private individual, Braque shunned the limelight and remained married to the same woman his entire life. In contrast, Picasso was a short, egotistical, outspoken, and unpredictable Spanishman who never stuck to one woman or painting style for a prolonged period of time. Hailed as the first celebrity artist, Picasso reveled in his very public status. However, despite their vastly different backgrounds and temperaments, Picasso and Braque complemented each other and contributed to the realization of a common vision with their joint creation of Cubism.

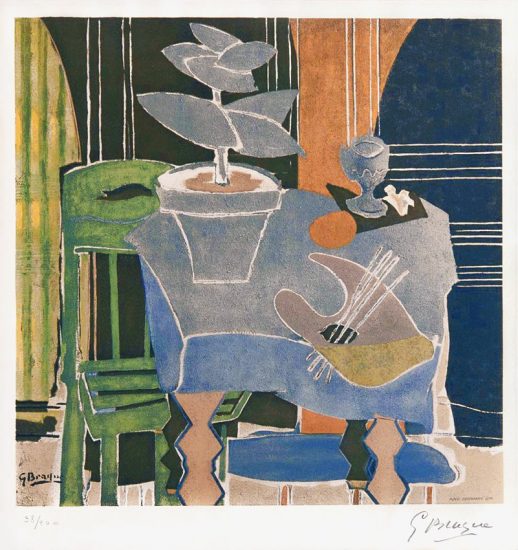

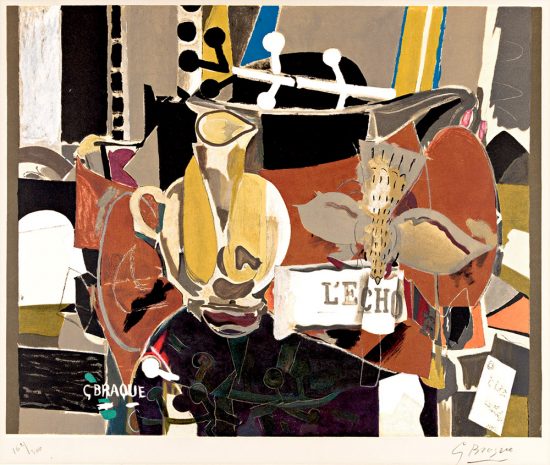

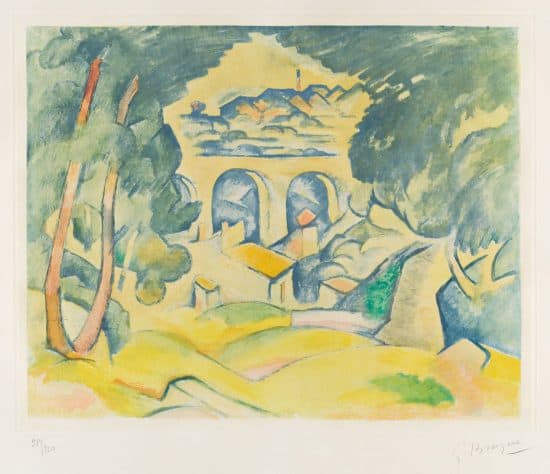

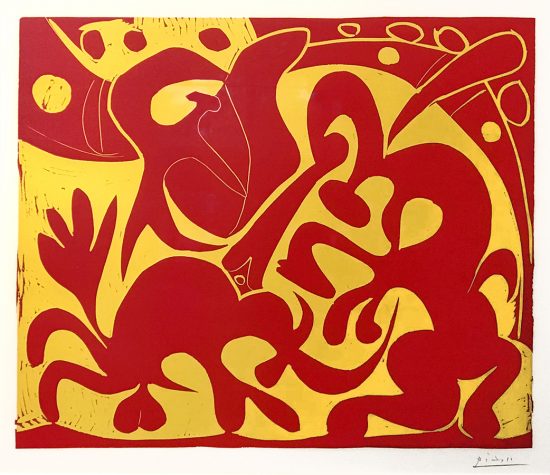

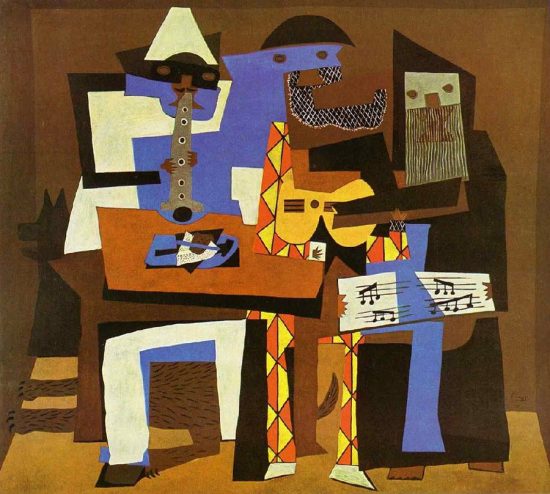

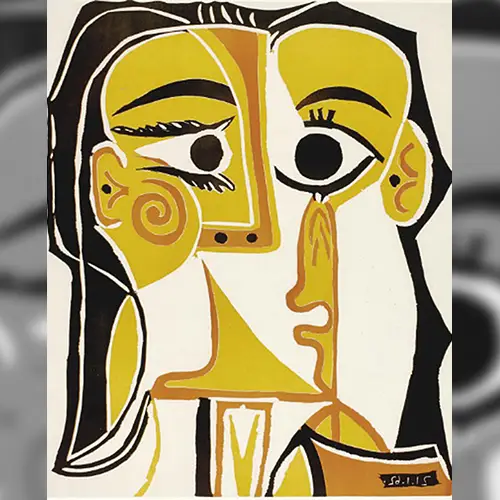

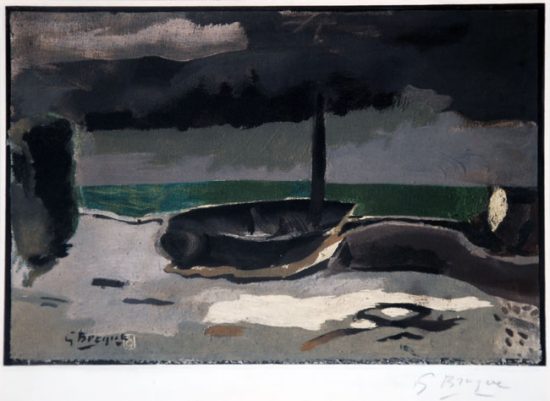

Both Picasso and Braque called into question conventional ideas about art as the imitation of reality. They initially drew inspiration from two key sources: works by Paul Cezanne and African art. Paul Cezanne’s use of fragmented space and ambiguous forms and the geometric shapes and figures apparent in African art, particularly African masks, paved the way stylistically for their development of Cubism. Together, Picasso and Braque developed a distinct Cubist style. Picasso shifted his focus from narrative imagery to pictorial design, while Braque channeled his creativity towards his use of materials and textures and the manipulation of light and space. While their Cubist works are visually similar, Picasso and Braque often strove for different aesthetic effects – Braque desired his works to maintain a sense of balance and harmony while Picasso strived to disrupt this sense of balance and harmony.

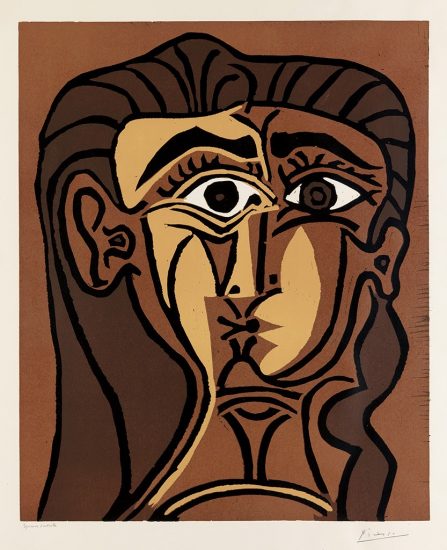

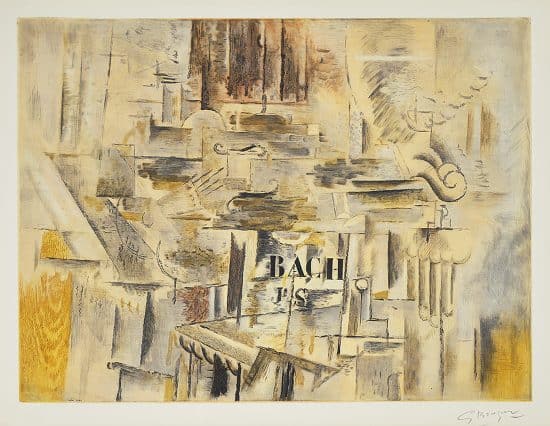

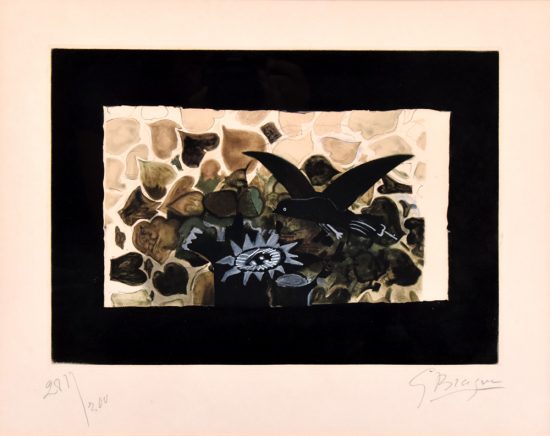

Picasso and Braque's art movement defined certain aspects of Cubism including distorted figures and forms and a monochromatic color palette of browns, greys, and blacks. They simplified figures and objects into geometric components and planes that may or may not add up to the whole figure or object as it would appear in the natural world and simultaneously depicted different points of view on one plane, suggesting a flat, two dimensional surface. In addition, Picasso and Braque experimented with pasting colored and printed pieces of paper into their paintings. Picasso is credited with inventing “collage” with his 1912 work Still Life with Chair Caning, while Braque is credited for inventing “papier collé,” or pasted paper, with his 1912 work Fruit Dish, and Glass. The difference between collage and papier collé is extremely subtle – papier collé refers exclusively to the use of paper, while collage may incorporate other two-dimension (non-paper) components, suggesting that both Picasso and Braque co-created these techniques together. Braque’s role in Cubism tends to be underplayed, as Picasso is often considered the more commercially acclaimed artist. However, both artists contributed greatly to the Cubist movement.

Picasso and Braque enjoyed a stint of productive and innovative collaboration until the fall of 1914, when Braque enlisted in the French Army early in WWI. Following the war, the two artists went their separate ways and never re-ignited their friendship. Picasso and Braque occasionally made snide remarks about each other, yet they remained loyal to what they shared from 1907-1914; they never expressed what transpired between them. As Braque recalled, ”Picasso and I said things to one another that will never be said again … that no one will be able to understand.” This dedication and respect is one seldomly seen in the art world, and their silence on what transpired signifies that they felt their time together was sacred.

William Rubin (1989), former director of the Department of Painting and Sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, best sums up Picasso and Braque’s relationship when he states, “The art movement of Picasso and Braque is unique in the history of art for its intensity, duration, and generative impact. No other modern style was the simultaneous invention of two artists in dialogue with each other. In the years of their association, Picasso and Braque not only produced a number of exceptionally great works, they created a visual language that could and would be used by artists with widely divergent aesthetic, literary, and political concerns.”

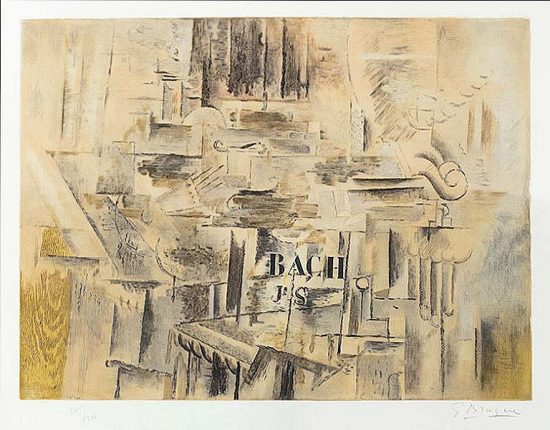

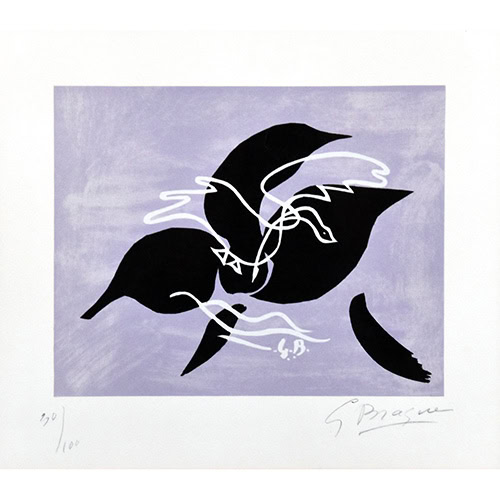

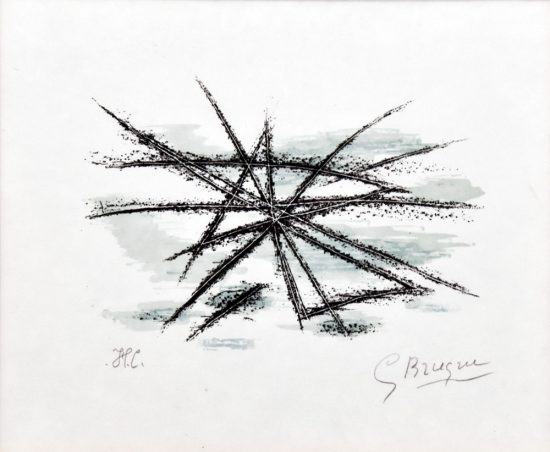

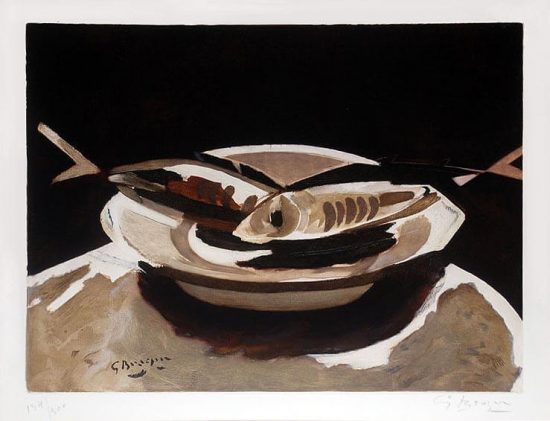

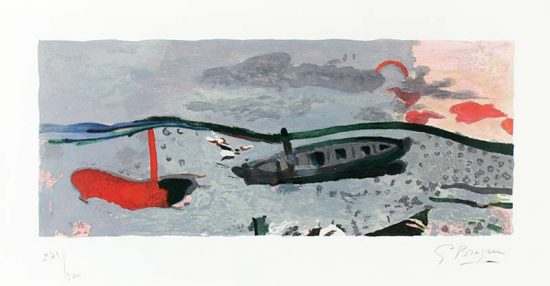

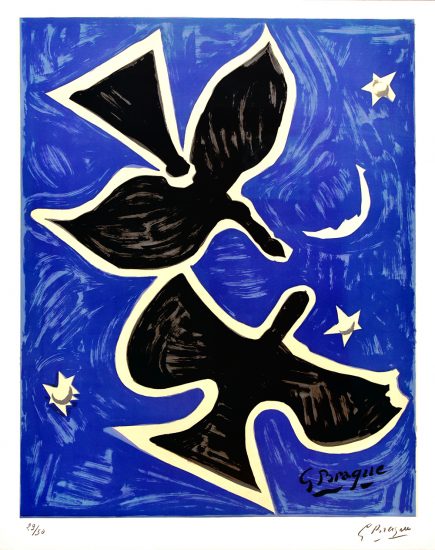

While the majority of Picasso and Braque’s works of Cubism are paintings, both artists also created stunning prints in the style of Cubism. Such Cubist prints are exceedingly rare and are often created after the image of renowned Cubist paintings such as Still Life with a Bottle of Rum (1911) by Picasso and Hommage a J.S. Bach (1911-12) by Braque. As both Picasso and Braque are credited with co-establishing and spearheading Cubism, these Cubists prints are iconic – they remain amongst their most collectible and treasured graphic works to date.

References:

- Brenson, M. (1989, September 22). Picasso and braque, brothers in cubism. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/1989/09/22/arts/picasso-and-braque-brothers-in-cubism.html

Enjoy our fine art collection of Georges Braque Still Life.

Enjoy our fine art collection of Pablo Picasso Still Life.

![Georges Braque Lithograph, Nature morte (avec un pichet et citrons) [Still Life with Pitcher and Lemons], c.1950](https://images.masterworksfineart.com/braque2243-550x420.jpg)