Frank Stella is a hard man to categorize. He has worked in what seems like every medium over his extensive career and has transformed nearly every one, expanding the technical and formal boundaries of painting, printmaking, and sculpture. A constant feature of Stella’s work, more so than perhaps any other artist, is change. His career began as a Minimalist, working with few colors and flat painted surfaces. Decades later, Stella is a self-proclaimed “Maximalist,” working with a rich and varied color palette and a wide-ranging set of mediums and techniques. What drove these changes and how did his practice reach its “Maximalist” height? The one aspect of his work that can encapsulate this trajectory is Stella’s continued exploration of space and depth.

Stella’s career began in the 1950s, while he was still in his early twenties. He launched onto the scene in conversation with other Minimalist artists. These early works are austere, revelling in cold surfaces that emphasize Stella’s assertion that “what you see is what you see,” a statement that became a sort of manifesto for the Minimalist movement. These early works, including his Black Paintings, Aluminum Paintings, and Copper Paintings, placed the focus on the materiality of the flat painted surface, eschewing any attempt to create depth or explore space. Rigidity characterized these works; Stella was careful with his placement of his lines, all of them straight and calculated, and all of them in white against their respective backgrounds.

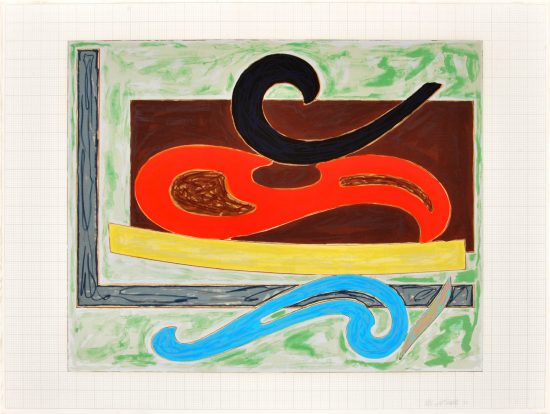

Stella began to branch out into both color and non-rectangular shapes in the mid-1960s, though the works were still strictly two-dimensional. The shift into three-dimensionality started in the 1970s when he began to engage with assemblage. The Polish Village series (1970-74) can be seen as a starting point. The artworks in that series are at once sculptural and textural, incorporating materials such as corrugated cardboard and felt. Though he was not creating free-standing sculpture at this point, the assemblages act as the emergence of Stella’s exploration of space, how it could be created, and how it could be occupied. In direct contrast to his Minimalist works, Stella traversed a new freedom in form. This was a critical point; from this point onward, the shift into “Maximalism” would be in full swing.

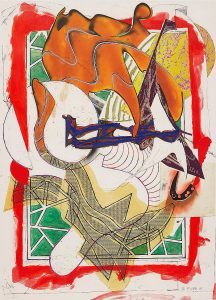

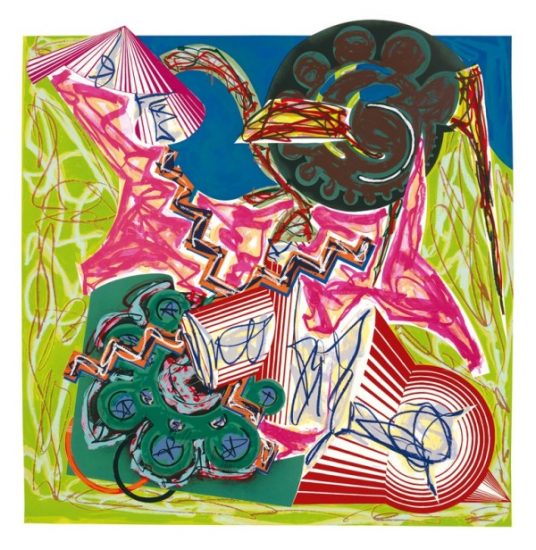

The formal experimentation of the 1980s and 1990s created a movement within Stella’s work that would permeate throughout the rest of his career. Stella began experimenting with free-standing sculptures and architectural projects in the 1990s. This venture into three-dimensionality forever changed his approach to artmaking. Brightly colored geometric forms meander around each other and wind around organically, Stella seemingly throwing his Minimalist roots out of the window. In these works, it becomes clear that Stella is paying attention to the relationship between his artwork and the viewer in a new way. This shift toward sculpture begins to ask questions about how his abstractions could extend outward, protruding into the world of the viewer, while also creating their own internal worlds, into which the viewer could be drawn.

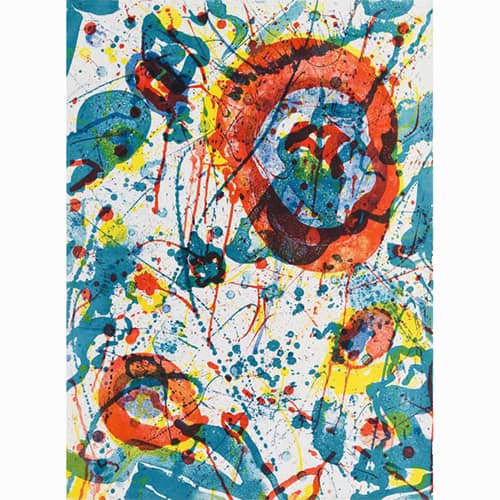

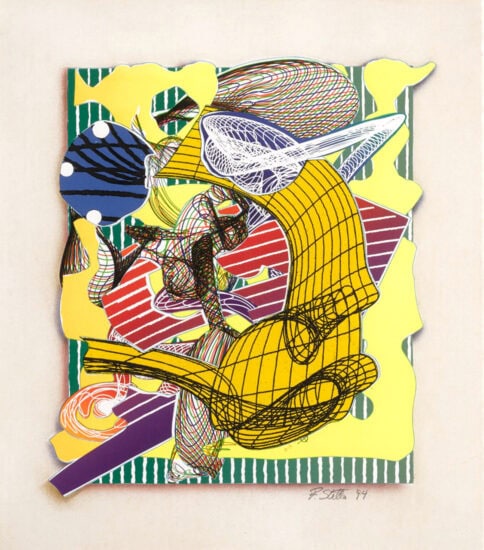

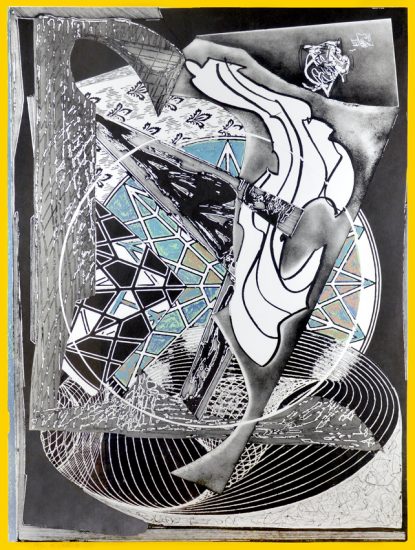

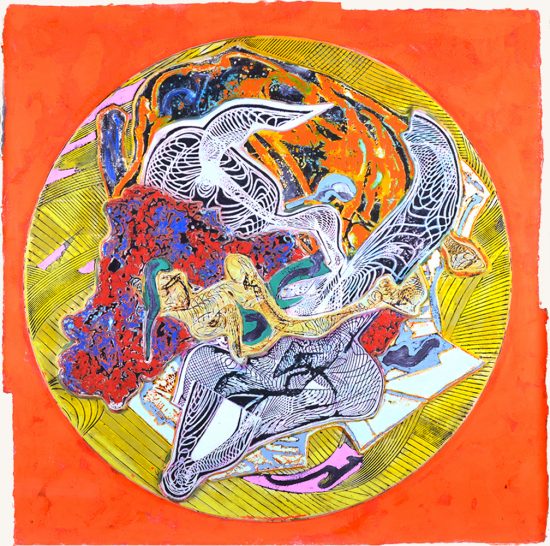

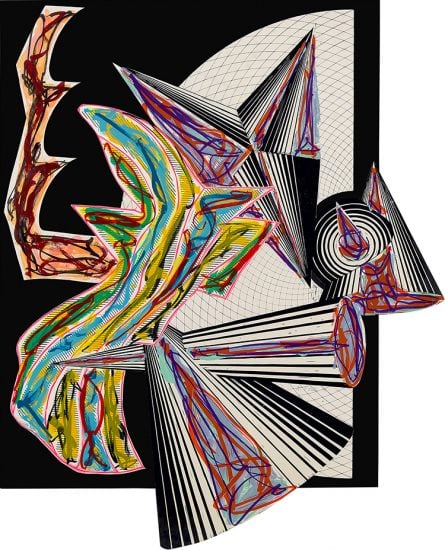

This new attention and interest in space was not reserved for his work in traditionally three dimensional forms. His printmaking, especially, as well as his painting and drawing similarly burst out of their frames. The two-dimensional work took the form of flattened sculpture, and while the sculpted forms began to take on the form of expanded prints. Organic forms overlap, each of them aware of their contact with the forms around them, flooding the confines of their pages. Stella’s “Maximalism” does not refer only to the compositions and colors being used, but also to the range of techniques. Stella’s association with printmaking is especially relevant to his “Maximalist” approach. He is known for his work in lithography, but rarely did he allow his lithographs to be just lithographs. Combining collage elements, hand-coloring, relief, etching, woodblock printing, engraving, and more, the “Maximalist” approach involved using an overwhelming number of techniques in a single artwork. The experience of viewing these artworks, even when only two-dimensional, is almost bodily as the eye weaves through the negative space between the forms and between the shapes themselves.

Even as his works have become increasingly intricate and exuberant, one thing that Stella hasn’t strayed from is his assertion that “what you see is what you see.” Even as his practice has tested the limits of the techniques he uses, his practice has never strayed from its insistence on materiality. He has never ventured into representational or figurative work. He is comfortable in abstraction, even as he pushes against traditional abstraction with every new experiment. The act of seeing is what his work, regardless of its ties to either Minimalism or “Maximalism”, is about—the way that the viewer interacts with the surfaces in front of them is, and always has been, Stella’s primary concern.

Browse our entire collection of Frank Stella prints.