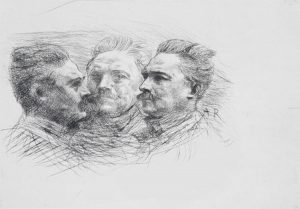

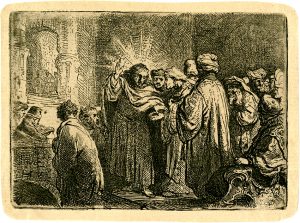

Drypoint can be traced back as far as the 15th century Germany artist Housebook Master who completed all of their works in drypoint. More commonly, drypoint is used in addition to other printing techniques, such as engraving, etching, or aquatint. Albrecht Dürer, mostly versed in woodcuts, completed 3 drypoint prints in his lifetime. Rembrandt was a frequent user of drypoint, but only in conjunction with engraving or etching. It was not a very popular method during the Renaissance due to the resulting small edition size. Drypoint was an easier medium to master than the difficult and technical engraving, which made it appealing to artists who were trained in drawing. In the 19th century, in part because of this accessibility, drypoint rose in favor for the creation of small editions of works, as opposed to the recreations of original works that were popular in engraving and etching at the same time. Drypoint isn't, however, a good method for making a profit off of ones’ art, as generally it required lots of time for less pay off in terms of finished prints.

An intaglio printing method, drypoint prints are created by carving directly into a metal plate. While any sharp metal object can be used for this process, there are tools that are made specifically for drypoint. This tool needs to be stronger than an etching needle, because it needs to displace metal, instead of the soft ground used in etching. Diamond-tipped needles are particularly effective and they carry the added benefit of never requiring sharpening. The downside is the cost, which can be a barrier for many artists. Another good option is the carbide-tipped steel needle. These are more affordable, but need regular sharpening. Traditionally steel needles have been used for drypoint.

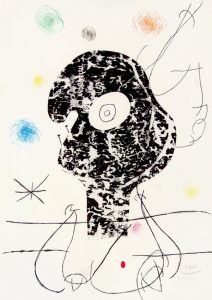

The artist draws directly onto the copper plate, throwing up a burr. This protrusion of metal around the lines is what gives the drypoint its distinct look. The burr prints a softer line, unlike the hard lines from etching and engraving. A thicker line is achieved by applying more pressure. After the image is complete the plate is inked and wiped clean. The artist must be a careful to not apply too much pressure when inking the plate so as to not compromise the burr before printing. The burr holds a large ink reservoir, printing in a deep, velvety black shade.

Drypoint is similar to engraving methods. A pointed metal needle, much stronger than an etching needle, is used to draw directly into the copper plate. The metal is displaced, creating what is called a “burr”. This protrusion of metal around the lines gives the dry point etching its distinct look. This method cannot give more than 15-20 good impressions because the burr wears down quickly with printing. The resulting lines are also shallower as compared to engraving and etching which contributes to the short lifetime of the plate.

Sources

Tate Modern. “Drypoint.” http://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/d/drypoint

Thompson, Wendy. “The Printed Image in the West: Drypoint.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/drpt/hd_drpt.htm (October 2003)

Browse our collection of drypoint fine art.