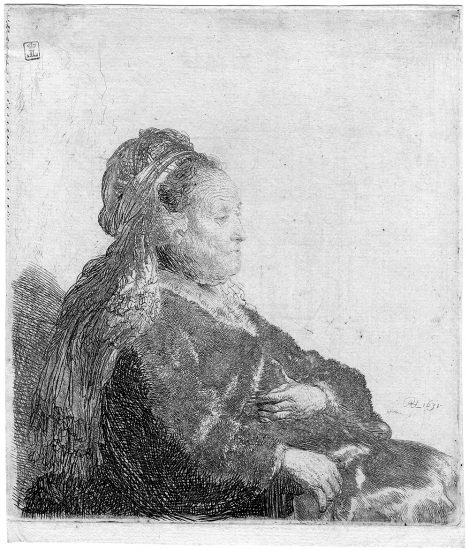

When Masterworks Fine Art acquires an artwork, we undertake a program of research and identification. Old Masters prints, such as those by Rembrandt, require special attention because documentation can be limited, works often exist in multiple states, and posthumous prints made from plates still in existence are on the market.

When researching a Rembrandt impression, we consider the image and sheet size, the type of paper on which the work is printed, and the watermark (if there is one). We consult Nowell-Eusticke, the authoritative catalogue raisonné for the artist, compare our results against the volumes by Hind and White & Boon, and turn to the recently-published Watermarks in Rembrandt’s Prints by Ash & Fletcher. These books describe, in one way or another, differences large and small between each printing of a single plate.

Rembrandt experimented with the effects of printing on different kinds of paper, and is known to have used vellum, calfskin parchment, creamy handmade European papers, coarse “oatmeal” papers made from the dregs of the papermaking vat, and the thicker, softer “Japan” paper (Ash & Fletcher, 11). Not all of these papers were made with watermarks or wire marks, as they are also known, but those that were can provide insight into the time frame in which a print was pulled.

As methodical studies of watermarks found in the graphic work of specific artists appear, the identification of these marks becomes increasingly valuable. It is a rare day when we uncover a full watermark on a newly acquired print. Finding even the tip of a crown or a partial cluster of grapes enables us to match that fragment to a documented watermark. If we can nail down what paper the work is on, we can at least be certain that the impression was not pulled before a certain date.

How does this relate to Rembrandt?

Say we determine that a certain watermark was produced in the early 18th century. A Rembrandt etching on that particular paper couldn’t possibly be a lifetime impression, given the artist’s death in 1669. Ash and Fletcher note: “Our research often revealed the use of the same paper in the same print or in prints produced within a few years of each other” (15). That being said, they continue, “Rembrandt may have purchased certain papers in quantity, saved them, and used them intermittently over the years” (Ibid). This passage underscores the difficulty Rembrandt scholars face in assigning prints an exact date. Though helpful, a paper’s dates of creation do not necessarily dictate the time frame for the printing of a specific state. A plate may have been etched one year and printed the next. It may also have been reprinted a decade later.

Information obtained through a watermark about a paper’s country of origin, dates of manufacture, and import history can narrow the time frame for an impression and authenticate the work. However, sometimes our search for a wire mark leaves us empty-handed, and we turn to determining the state of the print.