More than 15 studies of Rembrandt’s prints have been done since Parisian art dealer Edmé-François Gersaint compiled the first portfolio of the artist’s work in 1751, a number that underscores the challenge that his oeuvre continues to pose (White & Boon, v). These books provide essential information about each print; cross-referenced catalogue raisonné numbers identify each image, and a brief, meticulous discussion of the impressions and states in existence follows.

We look to Nowell-Usticke’s authoritative Rembrandt’s Etchings: States and Values before cross-checking the entries in catalogues by White & Boon and Hind, amongst others. Nowell-Usticke makes the following remark in his introduction:

"A great multiplicity of states seems to have always been associated with

Rembrandt’s etched work. I feel this idea is incorrect. Rembrandt was

basically a one state etcher. […] after completing his etching he would

carefully inspect it; only when he was satisfied would he remove the

varnish and pull about five trial proofs to check general appearance […]

If these proved satisfactory […] he would pull about twenty more proofs

before putting the plate aside" (14).

These early prints, created within Rembrandt’s lifetime, are known as lifetime impressions, and are the most valuable works on the market. The word also applies to those impressions that the artist may have pulled if an initial printing sold well. Nowell-Usticke estimates 25 more prints followed the “early” examples, and these he terms “intermediate”. The last prints are “late”. This simple nomenclature opens the door to a complex web of plates destroyed and existing, reprints, retouches and more.

An etching can exist in one state, or in nine and our job is to determine where the work in our possession fits in with the print’s history.

Catalogue entries ask the reader to scrutinize the shading on the edge of a cloak or look for additional horizontal shading on a window sill. States of a print can vary minutely, meaning correct identification requires careful examination. Without our extensive library, which contains rare books and is a source of pride here at the gallery, we would not be able to complete such comprehensive research.

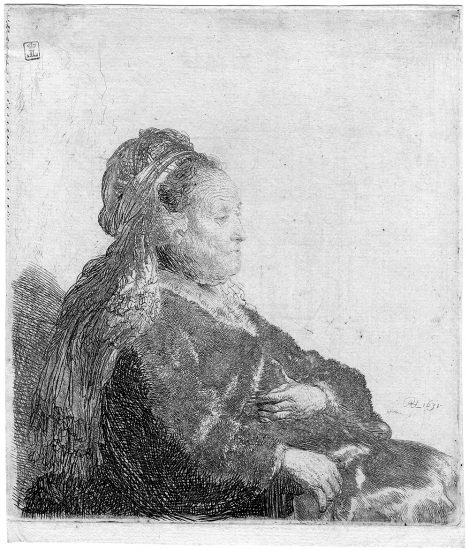

In the case of our Jakob Thomasz Haringh (The Young Haring), however, there was little room for doubt. The catalogue informs us that state III impressions of this print show a large picture added to the wall at left; state IV impressions are printed from a plate that has been, “cut down to head & shoulders only; the picture has been removed, leaving some traces” (Nowell-Usticke, B 275). The trimming of the plate narrows our options considerably, enabling us to name the correct state.

When we acquired Curly Headed Man With a Wry Mouth, our research was similarly short-lived. The plate, which has been destroyed, only existed in two states. Since impressions from the later printing show “The badly worn face & neck gone over with the roulette,” we had no trouble categorizing a first state print (Nowell-Usticke, B 305).

Navigating the catalogue raisonnès can be confusing at first, and we don’t always find what we’re seeking, but the research opens technical windows onto a great artist’s work and methods. And it’s surprisingly satisfying to find, yes, “The cross no longer touches the border at L. Fine diagonal L-R shading added below scroll (Making 3 directions)” – must be a State II Christ Crucified Between Two Thieves, Oval Plate (Nowell-Usticke, B 79).