Allow me to reminisce?

Although it was cold and blustery during my visit to Hundertwasserhaus (Hundertwasser house) a few years ago, these increasingly summery days remind me of this particular “house in harmony with nature.”

The multi-colored apartment building stands out in my mind, in front of some schnitzel gone bad (don’t ask) and an evening viewing art in the Museumsquartier, free of charge. Maybe the sunshine makes me wonder how the trees planted on the building's roof, terraces and balconies must look with their full coats of leaves.

Decorated with meandering mosaic lines and windows placed at odd angles (organically, the artist would say), Hundertwasser House is as original as its creator.

Upon the presentation of the architectural model to the public in 1980, Hundertwasser proclaimed, “Man has three skins: his own, his clothing and his dwelling. All three skins must continually change, be renewed, steadily grow and incessantly change or the organism will die.”

He discussed the “window right” of residents to alter the area around their windows, one outlet for life-giving creativity. Furthermore, “tree tenants” were to be planted throughout the building to give it a green shell that would improve living conditions for the entire neighborhood. The artist went so far as to stipulate that children be allowed to draw freely on all public walls, the plaster of which should be changed yearly for this purpose. Hundertwasser considered the environment as well as the structure, and designed walkways that undulate like rolling brick hills. Needless to say, his concept was ahead of its time.

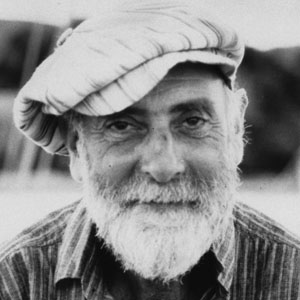

A native of Vienna who originally trained as a painter and printmaker, Friedensreich Hundertwasser (né Friedrich Stowasser ) became one of Austria’s most well-known, albeit controversial, artists. The name he took on, translating roughly to “Peace-Kingdom Hundred-Water”, underscores not only his individuality but his political identity. Throughout his life he championed everything from constitutional monarchies to environmental activism, driven by a commitment to freedom developed during his youth as a Jew in Nazi Austria.

Built between 1983-86 in collaboration with architect Josef Krawina, the building met with skepticism and outright hostility upon completion. Critics ridiculed the green roof and private balconies, and if we consider the often soulless architecture of the late 70’s and early 80’s, we (sort of) understand their aversion. Hundertwasser’s vision overflows with a too-muchness that we can trace to his shimmering colorful prints and paintings.

Labeled everything from a “municipal stillbirth” to “urban planning slapstick,” during its construction, the House has become one of Vienna’s most-visited landmarks. Such success and visibility can be traced to the artist’s innovation. The housing project accounts for quality of life and ‘green’ standards decades before the ideas entered common conversation. The profusion of rooftop gardens in San Francisco or even the High Line Park, New York (which, by the way, just began its own High Line Commission series for art installations) owe some debt to Mr. Hundred-Water and his vision.

Connecting the environmental and aesthetic in his search for quality of life, the artist defined art as vital instead of decorative.