It’s hard to overstate the impact Kenneth Tyler has had on the history of contemporary printmaking, due to both his endless innovation as a master printmaker and the jaw-dropping roster of artists with whom he has worked. The founder of the renowned Gemini G.E.L. workshop in California and later of the eponymous Tyler Graphics in New York, Tyler has been a half-century-long epitome of boundless ambition and ceaseless adaptability.

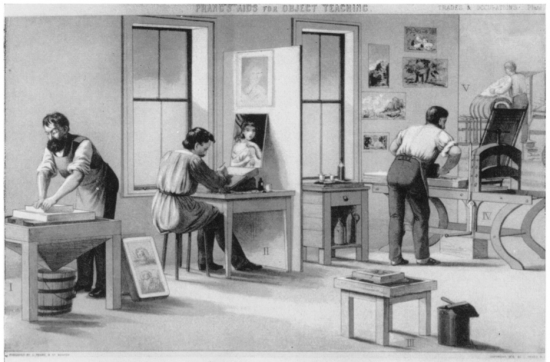

When a young Kenneth Tyler first became a printer-trainee at LA’s Tamarind Lithography Workshop in the 1960s, printmaking in America was withering as an artform. Written off as an archaic craft that lacked the urgency and emotion that ‘real’ art required, printmaking was in desperate need of a well-trained master printer to give it new life. Tyler quickly saw the ailments printmaking suffered from and the almost-limitless potential he could push it to. Within a few short years he had opened his own printshop, Gemini G.E.L., which drew in some of the greatest names in the 1960s art world, from Robert Rauschenberg to Frank Stella.

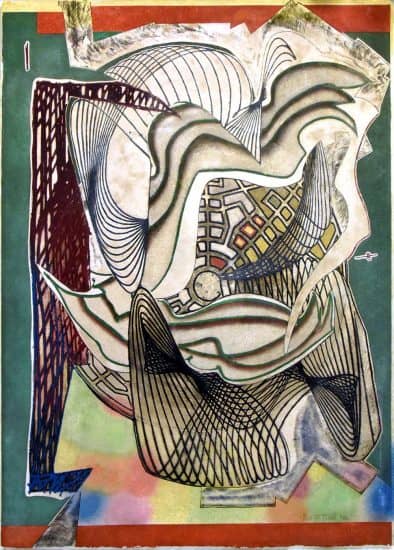

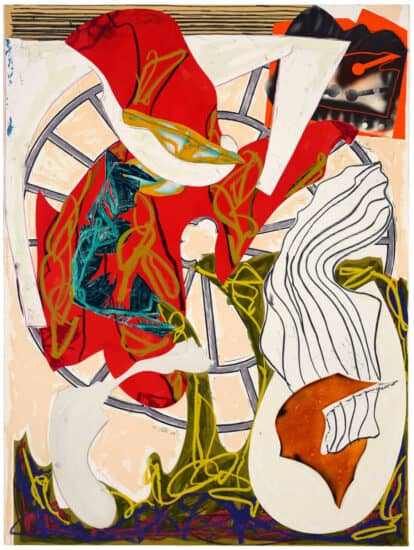

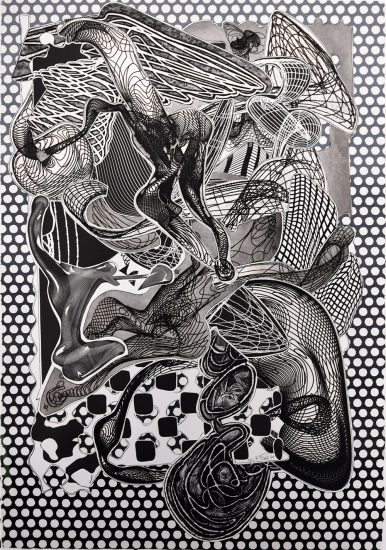

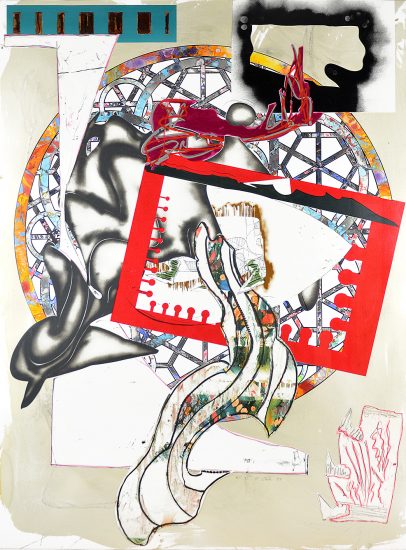

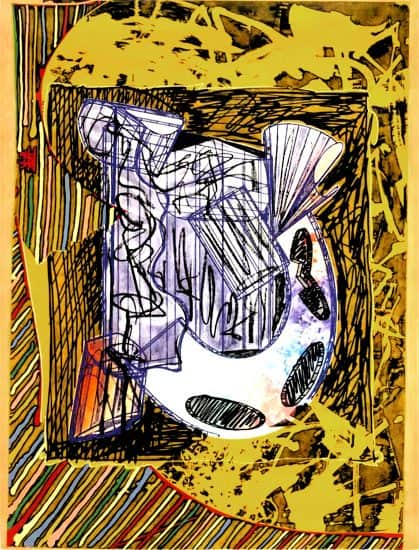

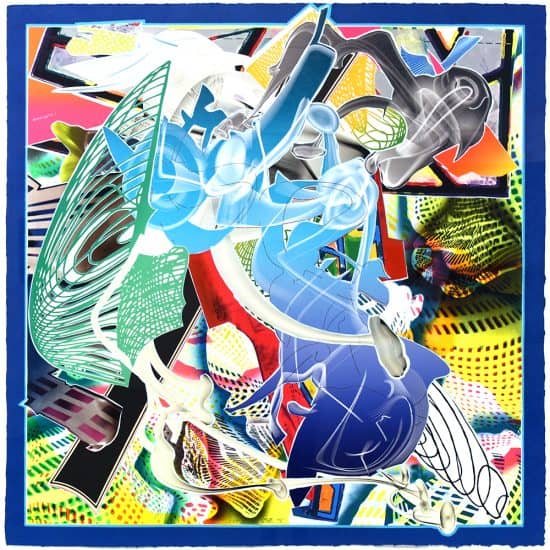

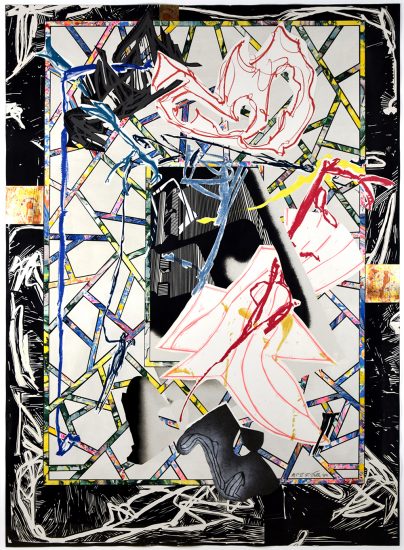

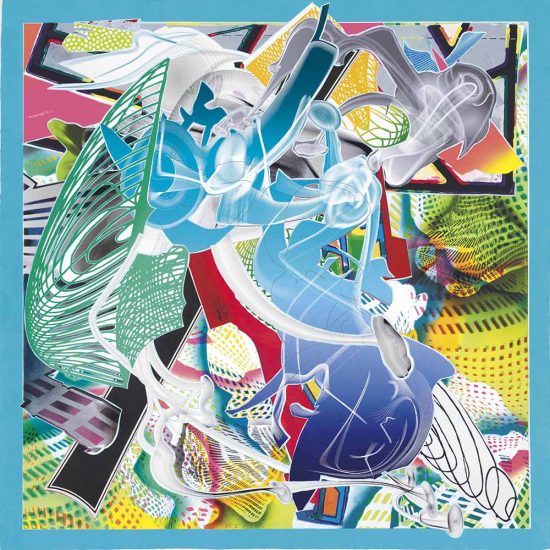

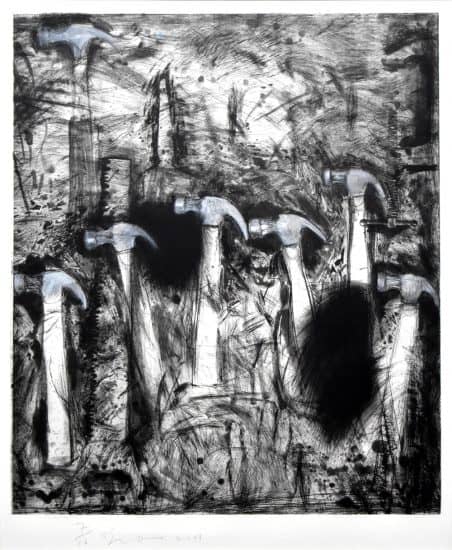

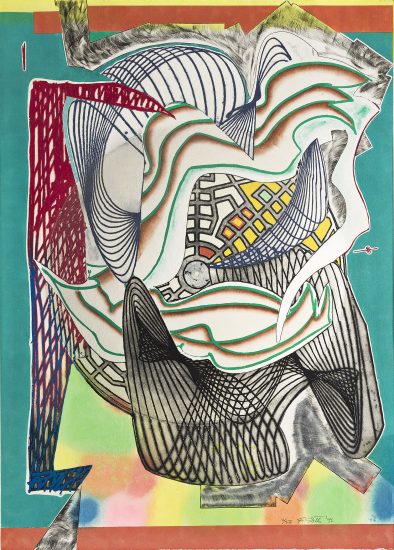

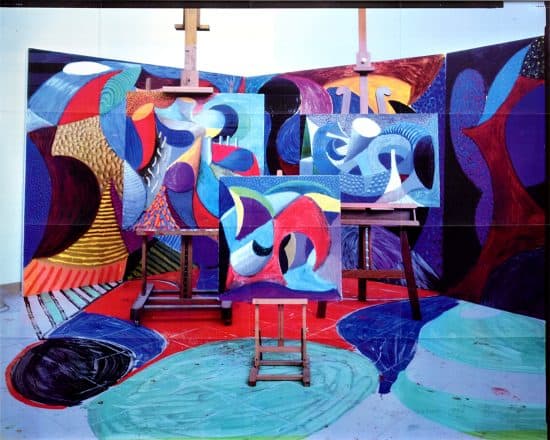

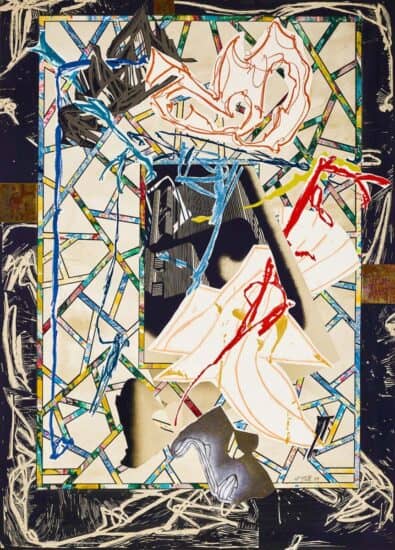

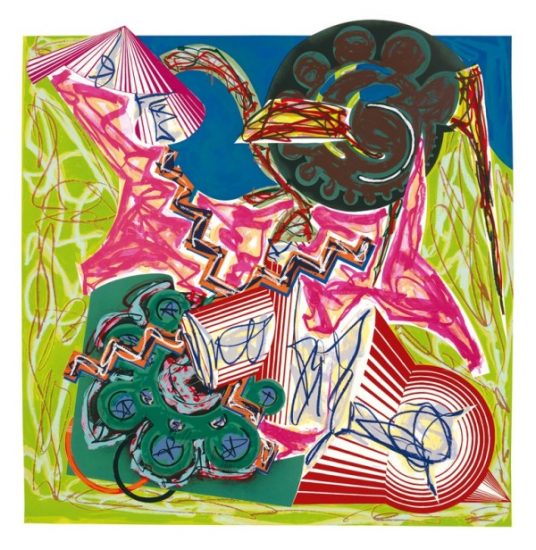

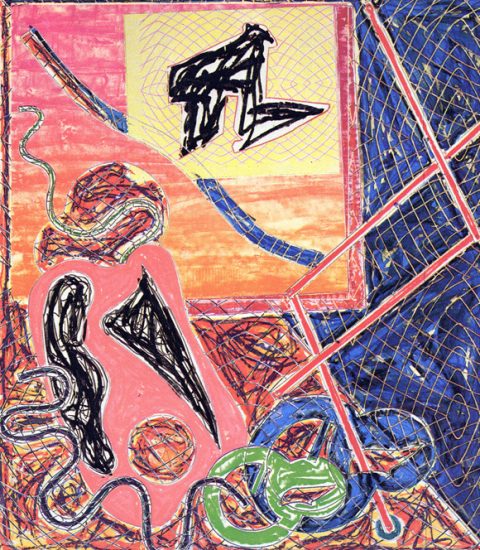

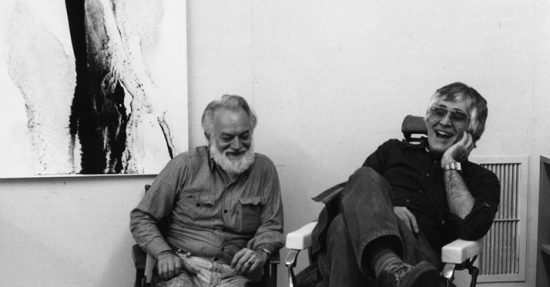

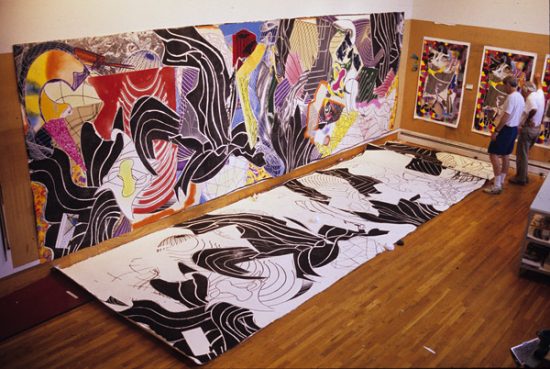

As impressive as Tyler’s star-studded artist roster is, the thorough adaptation of technique that is evident from artist to artist is the true phenomenon of Tyler’s career. The sensitivity with which Tyler approached each artist’s vision is evident in Robert Motherwell’s meditatively small and spiritual lithographs, the overwhelmingly baroque mixed media prints of Frank Stella, and Ellsworth Kelly’s shimmering and rich colored blocks pressed into paper pulp. If any artist approached printmaking with a skepticism of the medium’s potential, Tyler worked tirelessly to dispel their doubts. He adapted tools, invented new paper, and built specialized machinery, helping his artists not only realize their concepts but encourage them to hunt for new groundbreaking ideas.

An anecdote of Stella’s and Tyler’s collaboration genesis describes the resistant Stella continuously refusing Tyler’s request for Stella to do a project at the printshop. the dauntless Tyler showed up at Stella’s door with Magic Markers (Stella’s preferred medium for drawing) which Tyler had modified with lithographic tusche. It’s highly probably that were in not for Kenneth Tyler, some of his artists would have never approached printmaking; they certainly would not have achieved the rich variety of technique and style without Tyler’s ever-guiding and inspiring presence.

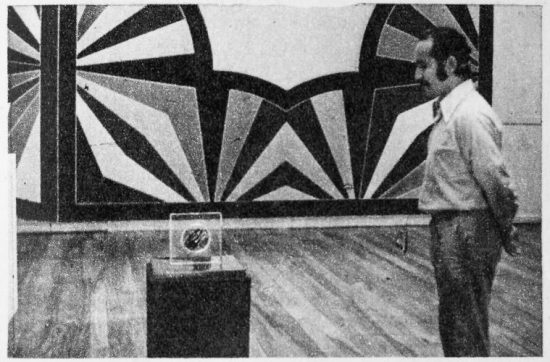

Tyler’s Gemini G.E.L. became a hub in the LA Art scene in the 70s, a finely-tuned operation that put out grandly complex, technically precise prints that had the clean coolness of machine-made works. This industrial sleekness drew criticism from draftsmen who scoffed at Tyler’s penchant for technological innovation and the suave California aesthetic of his entire workshop. Eventually, the master printer himself began feeling trapped in the city of angels and palm trees, feeling that his energy was sidelined by the social frenzy around him.

After a acrimonious split with the other co-owners of Gemini G.E.L., Tyler began dreaming of the quiet freedom of a countryside workshop. Never one to shy away from new opportunities, Tyler migrated to the east coast where he opened Tyler Graphics in 1974. The peaceful location of his new printshop revived Tyler’s enthusiasm for the medium, and his new-found proximity to his artists (most of whom were based on the east coast) opened the possibility of more intensive and extended projects.

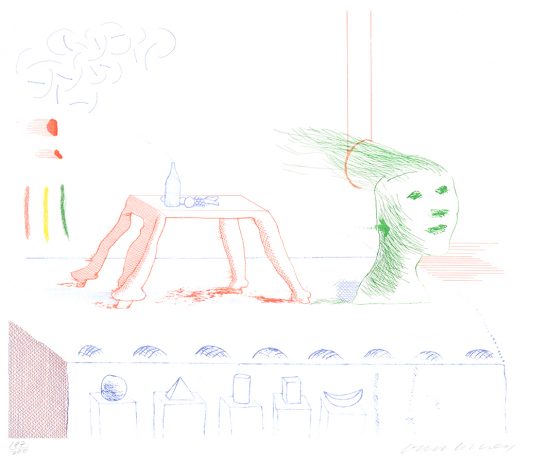

David Hockney, Jasper Johns, Helen Frankenthaler, Roy Lichtenstein and myriad other artworld titans had all through the years poured their energy and curiosity—always matched by Tyler’s own—into the workshop to produce editions that continuously pushed new methods and possibilities in printmaking.

The incredible revitalization and evolution Tyler brought to the medium approach legends of alchemic magic. The modest lithographs that defined printmaking before Tyler's time were propelled to cosmic scaled in a matter of decades, a transfiguration that culminated in Frank Stella's The Fountain, 1992. The sprawling chimera of printing techniques combines woodcut, etching, aquatint, relief, screenprint, and drypoint in colors with collage of handmade paper into one visual chronicle that stretches across 23 breathtaking feet.

The words Tyler’s artists spoke of him pinpoint his deeply human qualities that conjured magic in printmaking. “Ken makes artists feel they can’t fail at the project they’re about to undertake,” Helen Frankenthaler said of her 25-year long friendship and partnership with Tyler. A less flattering but no less accurate statement came from art historian and Stella’s ex-wife Barbara Rose: “He had this megalomaniacal belief that he could change [the printmaking] tradition through technology. He was pushy and he pushed artists to their limits.” Tyler's unrelenting stubbornness was noted by all, but it's precisely his unstoppable drive that made him the ideal collaborator.

One gets the sense of Tyler being both the matador and the bull, coaxing his artists to charge into uncharted territory and driving his horns at them till they force their creativity and ideas to new heights. Perhaps the best description of Tyler’s remarkable career comes from the master himself: “I knew I was better than the other printers, if for no other reason that none of them worked hard enough to amount to anything. So I thought, just concentrate on printmaking and see if you can make a go of it. Run a workshop.” This simple creed lay the groundwork for a 50-year-long chronicle of struggle, adaptation, invention, and magnificent art.

Bibliography:

- Armstrong, Elizabeth. Tyler Graphics, the Extended Image. Walker Art Center, 1987.

- Axsom, Richard. Frank Stella: Prints: A Catalogue Raisonné. Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation, 2016.

- Rosenthal, Mark. Artists at Gemini G.E.L.: Celebrating the 25th Year. Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 1993.

Image Credits:

1. https://kennethtylercollection.net/2015/09/04/if-this-chair-could-talk/

2. https://kennethtylercollection.net/2015/02/25/sid-avery-stars-on-camera/

3. https://kennethtylercollection.net/2016/12/19/technique-tuesday-frank-stellas-moby-dick-domes/

4. https://nga.gov.au/internationalprints/tyler/

5. https://nga.gov.au/internationalprints/tyler/