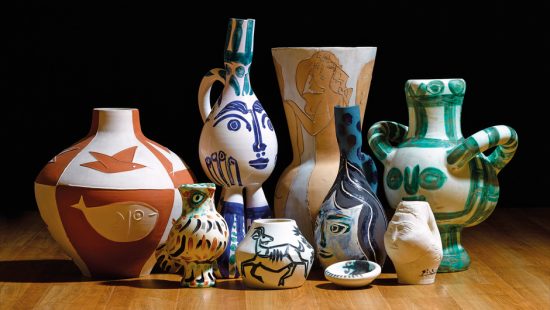

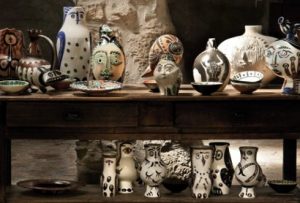

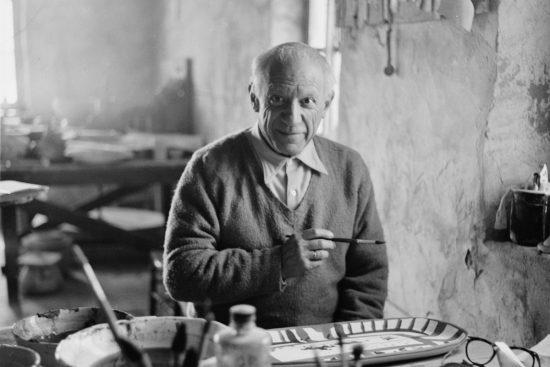

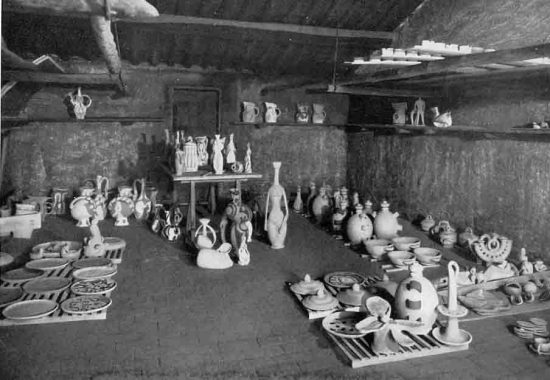

Pablo Picasso was a constant experimenter in everything that he tried. From painting to etchings to lithographs to linocuts and ceramics, there was nothing that he was afraid of trying: “I am always doing that which I cannot do, in order that I may learn how to do it.” This was never truer than his time spent in the Madoura studio in Vallauris where his artistic ingenuity and creativity came through in his creations of ceramic sculptures. The diversity of form and range of subject matter lend to these works a rareness that is unseen in his oeuvre.

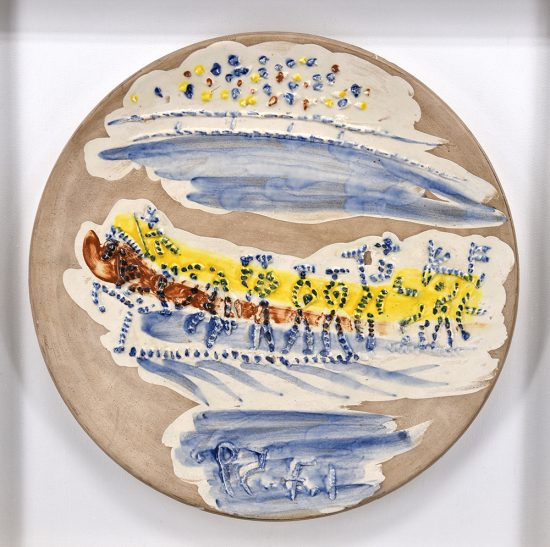

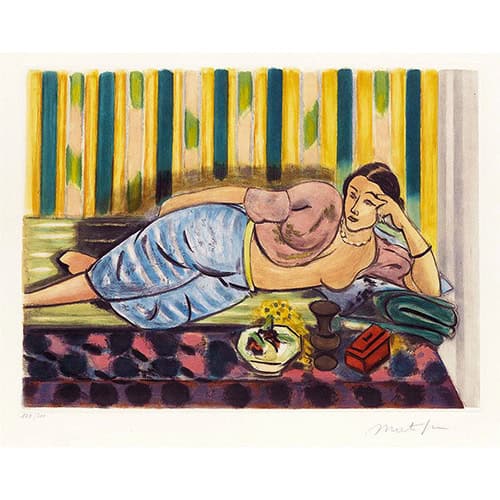

Pablo Picasso, Jacqueline at the Easel, 1956

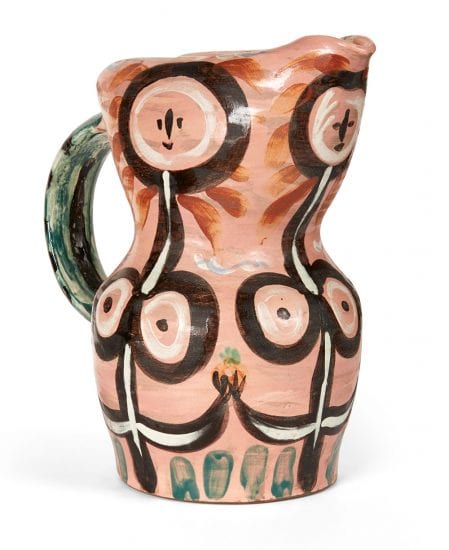

From plates to bowls to vases to innovative sculptural forms, Picasso pushed the boundaries of ceramic art with his ceramic plates being the gems. Picasso’s ceramic plates pushed his artistic expression into a defined form as there was but minimal space with which to work with. So what did Picasso do? He deceived our perception of the plate by using its contours, shape, and even the back to make the ceramic appear endless with his creative firing, line, and color choices.

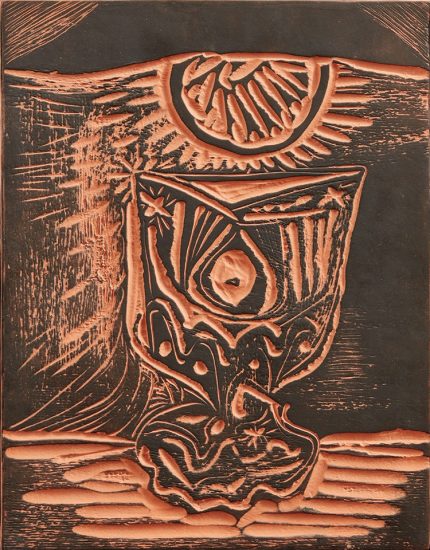

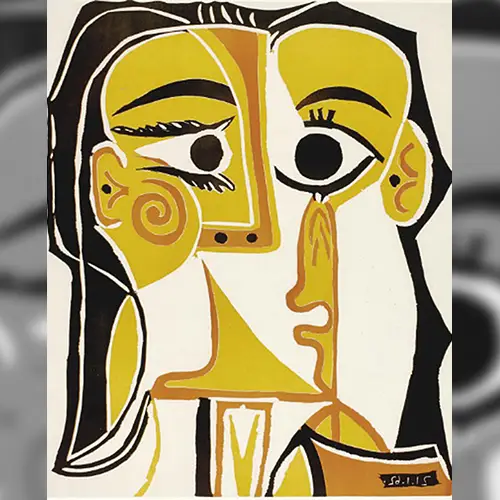

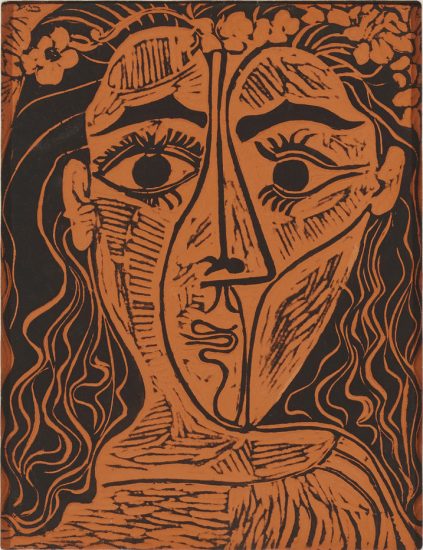

Pablo Picasso, Face in an Oval, 1955

A constant creator, Pablo Picasso utilized all kinds of shapes when designing ceramics, but for his plates, there are only four plate shapes that exist in the Picasso oeuvre: circular, oval, square/circular and rectangular. Picasso knew them inside and out, and knew how to contour them to fit his artistic visions. Each plate was chosen specifically to realize his visions and although only Picasso knows why he chose the plates that he did, we can guess based on his oeuvre.

The oval plate is essentially in the shape of an egg and has one size of around 33 cm x 40 cm. The majority of his works in this form are of abstract faces, so perhaps the form reminded him of people he knew or he saw it as the prefect form of self-expression. Most of these works appear to be deceptively simple until you look closer at their complex color scheme or detailed imagery. An example is Picasso’s ceramic, Face in an Oval, 1955(pictured) where there is a charismatic face gazing out against a russet and black background with a vibrant green border. The work appears simple yet upon closer look, the result is a stunning mixture of Picasso’s skill as a colorist and ceramic artisan, as the complex color scheme with a glazed surface almost makes the work glow.The circular plate is an even distance all the way around and ranges in size with diameters of 18.5 cm to 42 cm. Such a plate would allow Picasso to easily alter its contours during the firing process making them softer or deeper, depending on his choosing. This in turn would enable him to create a scene that was more balanced. An example would be Picasso’s ceramic, Jacqueline au chevalet (Jacqueline at the Easel), 1956 (pictured) that portrays Picasso’s last wife Jacqueline Roque painting at an easel. In this imagery the whole plate is taken up in equal balance leaving minimal space but still allows the viewer a whole scene as it drops over the edges of the plate.

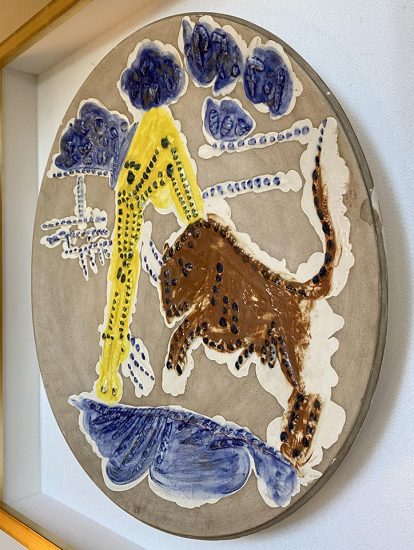

Fruits, 1948

The square/circular plate is a mixture of equal sides and rounded edges, but is elongated, having one size of around 21 cm x 21 cm. The deception of this plate appearing to be larger and longer than it is most likely allowed for Picasso to explore his visual frontiers on such a finite medium. He could place things anywhere he wished, as it needn’t be harmonized or coherent as it could hide behind the shape of the plate. An example is Picasso’s ceramic, Fruits, 1948, which portrays an abstract cactus in the middle of the plate, with flowery strokes creating the border. There is no harmony in the work as the cactus is uneven and the border flowers are heavily dominant around one corner. However the cactus anchors the composition as it rests in the middle and with the flowers on the lip, your attention is always being drawn to somewhere. The shape of the plate assists in utilizing the lack flow, which is a brilliant deception to the eye.

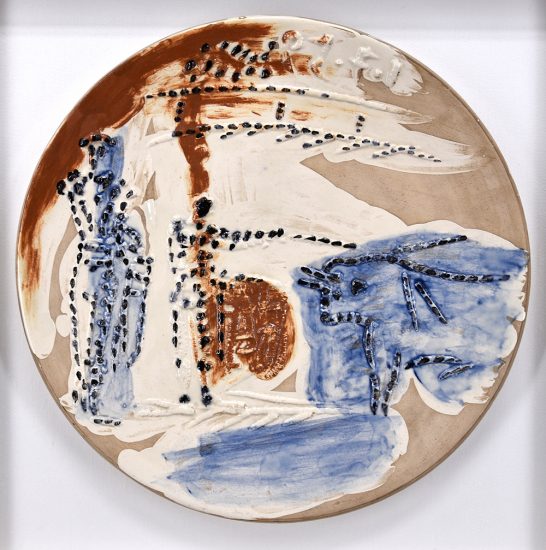

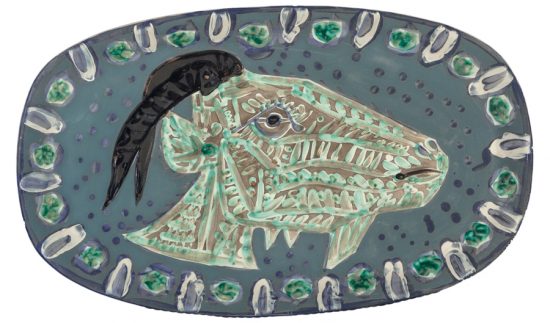

Pablo Picasso, Goat’s Head in Profile, 1952

There is always something new to discover in Pablo Picasso’s ceramic plates and that is the beauty of their form; the fact that they are three-dimensional yet lend themselves to a two-dimensional surface making for a grand illusion. The details, the color, the contours, and the brushwork all tell a part of the story of the creative process for Picasso. The other part is in the imagery itself, the inspiration behind the creation.The rectangular plate is longer on one side than the other and has two sizes, one at 39 cm x 32 cm and a larger one at 51 cm x 31 cm. Picasso utilized this form mainly for portraits, so it is easy to see that such an elongated plate could easily allow him to add features and details that he was not able to do on the smaller forms. The length also highlights the boundary of the lip, which is naturally softer in this form of the plate therefore enabling him to create the stronger borders that are seen in most of the works. An example would be Picasso’s ceramic, Goat’s Head in Profile, 1952(pictured) which displays a beige goat in green highlights against a beautiful blue background bespeckled in dots with a strong border. This goat is perfectly framed by the rectangular form of the plate, which deceives our eyes from recognizing the goat’s finite existence. So enthralled are we with the details that make the imagery appear endless, that we never seem to notice we’ve been mislead which is why Picasso took such pleasure in the ceramic medium.

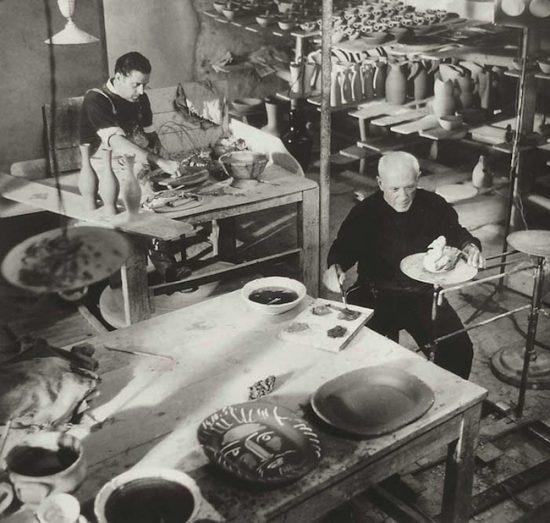

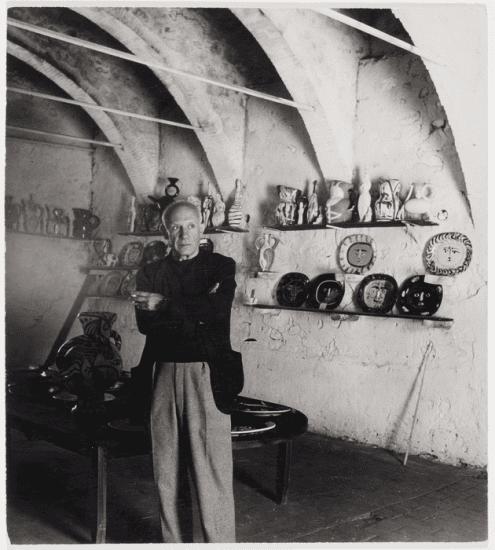

Pablo Picasso and his pet goat Esmeralda

Once remarking on how “sculpture is the art of the intelligence,” Picasso could certainly say that as the sculptor he is molding the intellectual. This can be seen in his ceramic plates where there is such an amazing diversity of themes: everyday life, plants, animals, insects, bullfighting, women, men, abstract faces, landscapes, cities and mythology. Each speaks to Picasso as a person, and each exists in a truly unique way as no two themes are ever represented the same in his ceramic plates.

Taking inspiration from everyday life, Picasso’s ceramics involved still lifes, plants ranging from flowers to cacti, animals ranging from horses to bulls to owls to fish to goats and insects. He had a large house with which to use for inspiration and had an owl, a goat, mice, dogs, and reptiles that he liked to surround himself with, often going on walks to connect with nature and unwind. As a man who constantly needed to refresh his perspective on life, he found nature to be a constantly changing and isolating, which mirrored his personality and was perhaps why he felt such a connection towards it.

Another close connection Pablo Picasso had was with bullfighting. Having grown up in Spain where the bullfight was dominant, Picasso become obsessed from an early age. As a young man he would even earn admission by selling his works of the bullfight for tickets. Thus the imagery and emotions were deeply engrained in his memory, and the scenes captured on the ceramic plates are his most cherished as they were created with such a tenderness and fervor, that it’s almost as if Picasso was reliving each experience. This could be why his plates are so heavily centered on this theme, as he did not return to Spain for quite some time and perhaps due to his old age wanted to recapture the memories and feelings of his younger years.

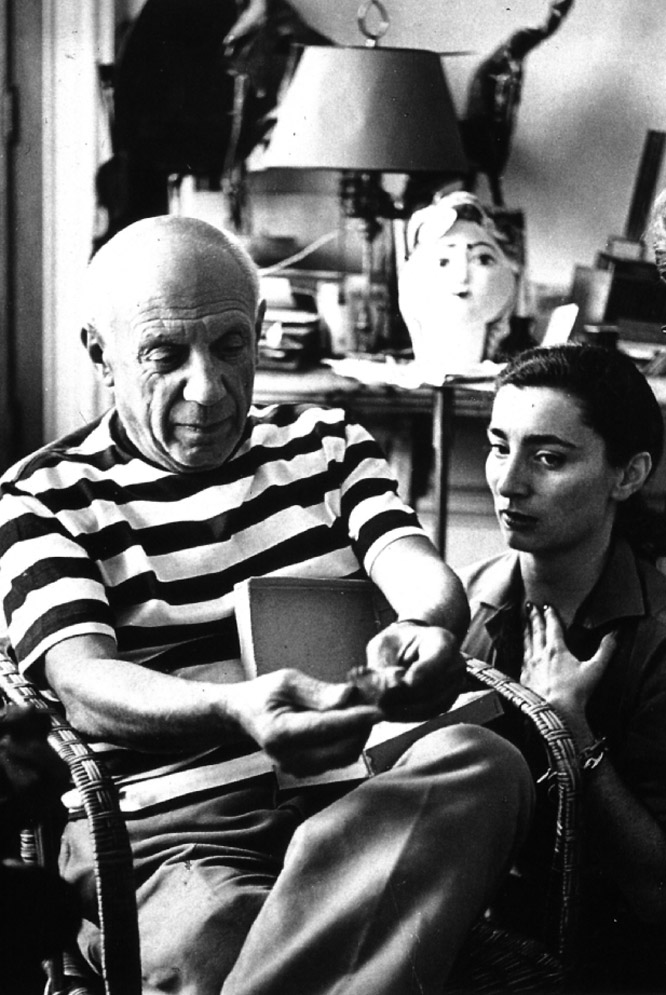

Pablo Picasso and Jacqueline Roque

Besides bullfighting Pablo Picasso had another obsession, women, and had several muses over the course of his life. Each had important roles in the artist’s oeuvre, but in regards to his ceramic plates, it is his beloved second wife Jacqueline Roque who is featured prominently as she worked at the Madoura ceramic studio and that is where they met and fell in love. She became a rousing force behind Picasso’s ceramic creativity and her features are easily distinguishable by the pointed nose with which Picasso portrays her.

Pablo Picasso, Visage D’ Homme 1955

Chavin Head, Chavin, c. 900 – 200 BC. Peru

Besides his portraits of men, Pablo Picasso’s ceramic plates also feature portraits of abstract faces. The abstract faces come from one of Picasso’s favorite inspirations, the Chavin. An ancient civilization that developed in the northern Andean highlands of Peru from 900 BC to 200 BC, Picasso drew inspiration from their patterns, abstract expressions, supernatural and deformed shapes. “Of all of the ancient cultures I admire, that Chavin amazes me the most. Actually, it has been the inspiration behind most of my art”.

Outside of culture, Pablo Picasso was also inspired by the landscapes and cities that surrounded him. The most important featured on his plates being the villages and scenery in the south of France where he settled down in his later years, particularly Vallauris, where the Madoura ceramic studio was located. Picasso looked to his surroundings to not only find beauty and meaning, but to represent the communities that had so warmly embraced him as well. A representation that was important to Picasso as it helped to solidify his connection to the location and make him feel apart of something, as he never truly felt like he belonged anywhere.

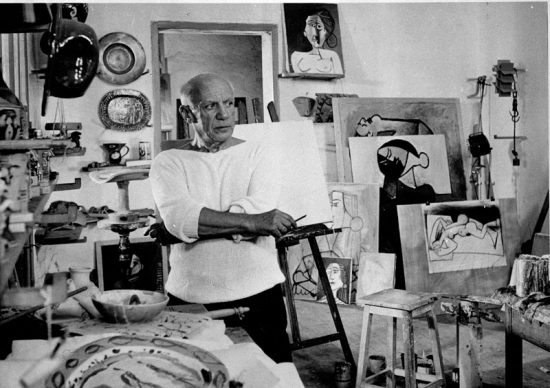

Pablo Picasso taken by Edward Quinn

Feelings such as those are why Pablo Picasso had such a strong connection towards mythology. Quoted as saying, “everything you can imagine is real, ” this other world that he found himself preoccupied with allowed him to express his inner feelings through the representations of the Faun, Centaur, and Minotaur. These intimate reflections make for some of his most decorative and detailed works on his ceramic plates. In portraying the Faun, Picasso looked back to his experiences as a lothario, a fun and happy lover. In portraying the Centaur, Picasso represented his failure to properly find his niche in society. In portraying the Minotaur, Picasso displayed his troubled life of self-loathing and depression, his lowest ebb. All of which powerfully combine to tell the journey of his life, a story that is expressed brilliantly in his plates.

With such inspiration at his disposal and the perfect medium of a ceramic plate with which to place them on, its no wonder that they are today some of his most revered and sought after works. As a man of many talents and moods, Picasso never stopped experimenting, saying “He can who thinks he can, and he can’t who thinks he can’t. This is an inexorable, indisputable law.” Picasso’s ceramics are perhaps the greatest testament to that belief for he created them with no prior knowledge or skill, but went in with passion, inspiration, and a fire to learn and create. Known as El Maestro (“the master”) of modern art, his great imagination and outstanding skill stand the test of time, as do his magnificent ceramic plates.

REFERENCES:

- Duncan, David Douglas. The private world of Pablo Picasso. New York: Harper & Bros., 1958.

- Ramié, Alain. Picasso Catalogue of the edited ceramic works 1947-1971. Vallauris: Madoura, 1988.

- A Tale of Two Picassos (link: http://daily-norm.com/2013/02/26/a-tale-of-two-picassos-the-1901-prodigy-and-the-introspective-illustrator-of-mythology/ )

- Chavin: Inspiration for Picasso (link: http://culturepotion.blogspot.com/2010/08/peruvian-art-that-inspired-picasso.html )