Analysis by A. Evans, Masterworks Fine Art Gallery

- Beyond Frida, O'Keeffe, female artists' influence on Art History vs. gender equality don't necessarily overlap

- Women are portrayed as passive, powerless for the enjoyment of men in 19th/20th c. art

- Popular female artists in the 19th/20th c. concentrated on individualism while other female artists critiqued the patriarchy directly

- Gender inequality guides Art History, and education must include its glaring presence

The subject of, or inspiration to, fine art is often a woman. However, the women involved in art's history go beyond the final product's mastic composition. Some of them earned their fame from their canvas, while others used the deviance of their art as a weapon against their oppressors.

A common summary of women in Art History goes like this:

- Mary Cassatt's mother and child, and her relationship with Edgar Degas that got her recognized by the Impressionist circle in Paris

- Georgia O'Keeffe's flowers, and her relationship with photographer Alfred Stieglitz who put her in the limelight

- Frida Kahlo's self portraits, and her relationship with Diego Rivera

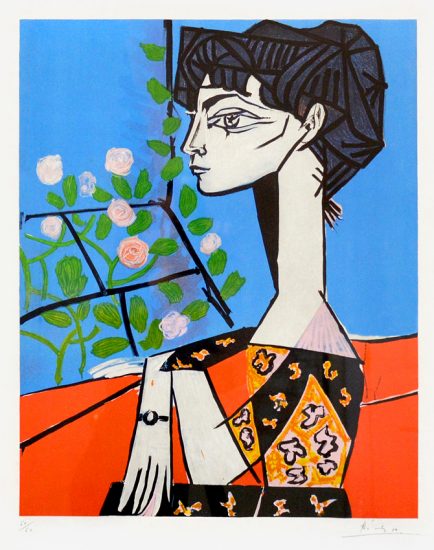

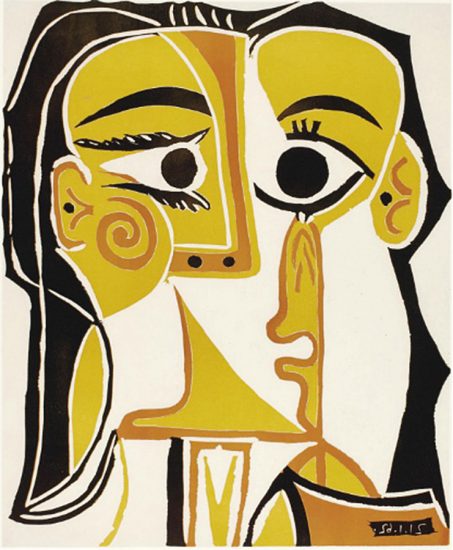

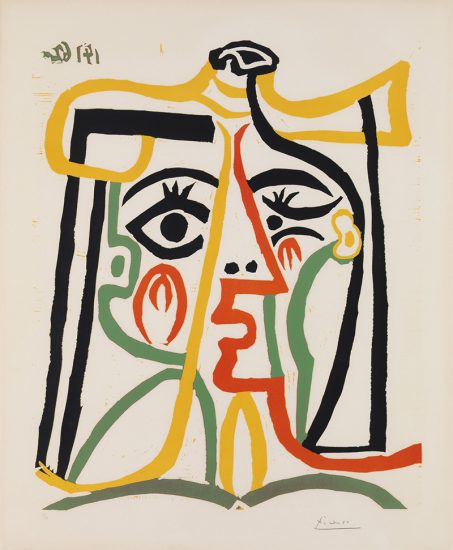

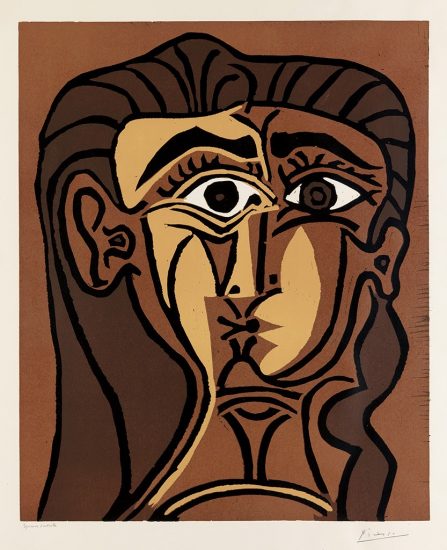

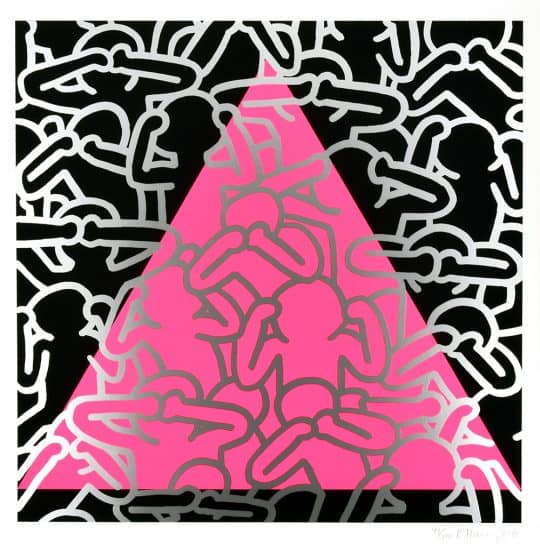

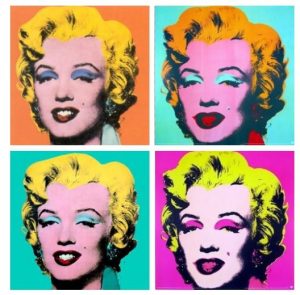

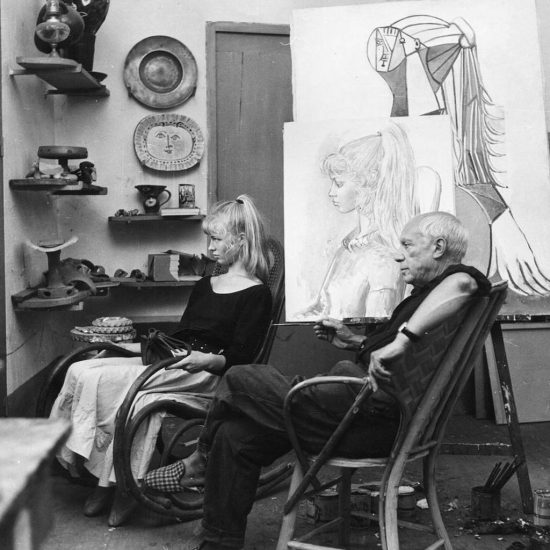

And then there's the famous female subjects of Art History. Going beyond Mona Lisa's smile, Warhol's Marilyn obsession or Picasso's fleeting adoration of Jacqueline, let us focus on those female artists who influenced the last few centuries of gender equality, whether through art or activism.

“This is so good you wouldn’t know it was done by a woman.”

-- German painter Hans Hoffmann's (1880-1966) compliment to Expressionist Lena "Lee" Krasner (1908-1984)[1]

Women subjects of both male and female artists are usually passive and powerless, so much to the point that citing specific works is unnecessary; just think of almost any famous painting of a woman and she will likely lack any substantial agency. Since men dominated the purchasing of art[2], this defines the male gaze[3]: Female power is unattractive to men.

Albeit less famous than other works of their time, there are historical works created by women that depict a woman with agency and purpose, and paying little mind to what was expected of a female subject or of a female artist.

Examples are Sofonisba Anguissola showing women not too happy about their uncomfortable attire, Elisabetta Sirani drawing her own blood to prove she is not weak in the face of torture [5], and Artemisia Gentileschi's artistic reaction to her sexual assault, as seen here, here, here (a rape victim, Lucretia, raising her bosom, possibly to better expose her heart, before she took her own life), here, and here (notice the thumbscrew, which was the same tool used to test her virginity [9]).

In a time when the portrayal of a powerful woman was not desired in art, but her love for her man was a common focal point, a crossroads was created where a female artist must decide whether she wanted one or the other, but not both.

Powerful female figures in world history, such as Cleopatra and Joan of Arc, are often depicted as beautiful women. However, historical accounts of Cleopatra lack descriptions of physical beauty. Jehanne d'Arc's (Joan of Arc's) [10] appearance seemed to be of little importance during her lifetime, but her depictions in art show her as increasingly beautiful over time as folklore set in. King Charles VII's chamberlain described her:

This girl is reasonably good-looking, and with something virile in her bearing... has a happy expression; so great is her strength in the endurance of fatigue that she could remain completely armed during six whole days and nights.

Despite the lack of historical primary sources to cite, attaching beauty to these women in art infers that their power came from the one allowable source of female power: a woman that strong must have been extremely beautiful.

Side note: d'Arc's beauty is lightly mentioned by her fellow soldiers, but more importantly, they mention how those feelings of lust were diminished in her presence, "and it seemed that this was almost miraculous." Her presence is even described as nullifying the thoughts and discussions of sexual desires by her fellow male soldiers.

"Well-behaved women seldom make history."

Pulitzer Prize winning historian Laurel Thatcher Ulrich's famous quote and her essay of the same name, "Well-behaved women seldom make history", highlights how the insubordination by notable women is often a requisite for them being written into our history books. However, does this hold true for the female artists of Art History?

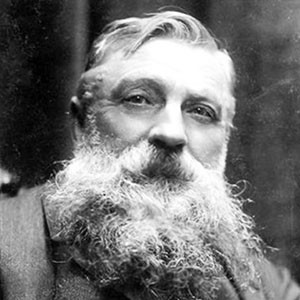

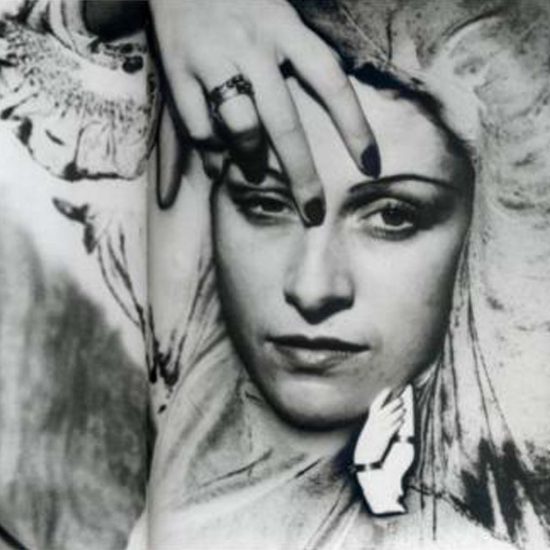

Camille Claudel (1864-1943)

French sculptor Camille Claudel (1864-1943) (pictured at the top of this article) was described as

"a revolt against nature: a woman genius." [11]

This same art critic follows up that being a woman unfortunately overshadows her genius, and that "if she were a man, she would have great success."

The first version of Camille Claudel's The Age of Maturity (1894-1900) centers around a male figure who seems passive, to the point of near collapse [12] while being guided by two women in opposite directions. The five-year progression of this work began with one of the women successfully pulling the man toward her, and ends with that same woman's weakened grasp begging for him to stay. (This final version may have been destroyed by Claudel herself.) Although Claudel touched on common themes, this impassioned sculpture uniquely emphasizes the woman’s conflict and deemphasizes the male. When looking at all of her works together, one can infer that we are witnessing her personal struggle between wanting to be strong and wanting to be loved.

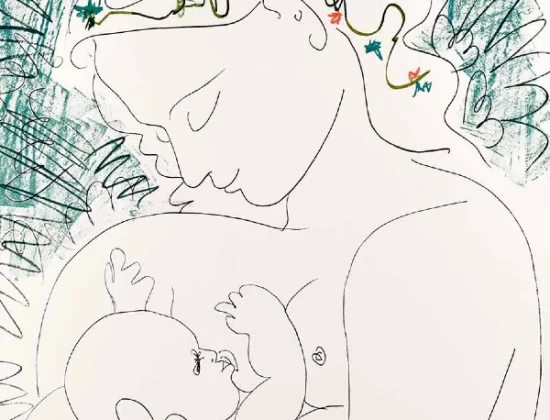

Mary Cassatt (1844-1926)

American Impressionist Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) emphasized the strongest human bond that only exists between a mother and her child. She also emphasized a woman's right to vote [13]. As a Parisian "New Woman" in the Victorian era, she exercised control over her own life—personal, social, and economic—while still being considered a well-behaved proper Victorian woman. However, another version of the New Woman at that same time "wore pants and was delighted in upsetting the status quo... She craved sensation."

Cassatt was one of the first American women to exhibit at the acclaimed Paris Salon in 1872, and she remains one of the most well-known figures in Art History today.

Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986)

"I have already settled it for myself so flattery and criticism go down the same drain and I am quite free," said Georgia O'Keeffe (1887-1986) of her critics who claimed to know her artistic intentions. "You write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see – and I don’t." She was insistent on being considered an artist and not a female artist, and consistently denied the validity of Freudian interpretations of her art. She considered her art about "putting the right thing in the right place." [14]

Although O'Keeffe was not outspoken on gender equality, her influence on the topic is evident through her independent personality. Despite her lack of activism, artist Judy Chicago (born 1939) gave O'Keeffe a prominent place in her popular installation of famous female figures in The Dinner Party (1979) [15].

Frida Kahlo (1907-1954)

Mexican surrealist painter Frida Kahlo's (1907–1954) personal reflection of reality was rife with her ongoing physical pains and psychological state. She’s quoted as saying,

“I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.”

Kahlo's use of "jolie laide" (French term, translates to "beautiful ugly") directly challenges the constant pairing of female power with physical beauty. Her subjects' unsympathetic expressions challenge the commonality of the passive woman, and have no interest in appeasing the male gaze. Instead of a litany of muses, she described her use of herself as her subject, "I am my own muse, I am the subject I know the best." Her legacy lives on beyond her art and beyond her popular relationship. Unlike her personal life, her legacy lives comfortably in Mexican, American, and Art History as an individual who wore her struggles on her sleeve, with little regard for the patriarchy.

Pussy Riot (2011-present)

As their name shamelessly states, the Russian punk rock group Pussy Riot (2011-present) uses their artistic talents, from music to visual arts, to stage guerrilla performances centering around the demand for equal rights. Along with their anti-authoritarian stance, mainly against Russian president Vladimir Putin, the all-female group related to the women of the 2010s much like riot grrrl and Guerrilla Girls of the previous decades.

Their female-empowering stance was seen as so subversive by the Russian church that the (appropriately named) Patriarch of Moscow considered the movement "very dangerous, because feminist organisations proclaim the pseudo-freedom of women". What?

From being arrested for "hooliganism", to being imprisoned for two years, to being horsewhipped and defenselessly beaten in public by male police (video), Pussy Riot has continued their protest in the form of curated art exhibitions (video) as their next platform for the same cause.

Conclusion

Women were barred from receiving education from prestigious art schools, such as the acclaimed École des Beaux-Arts in France until 1897, and were still mostly encouraged to pursue art forms like textiles, considered “decorative arts”, and not “fine art” [17]. If a woman took interest in painting or printmaking, she was to concentrate on landscapes, and, at best, portraiture of famous figures [18], but rarely of historical events. Sparse education and narrowed subject matter offered the "well-behaved" woman artist of the 19th and 20th centuries a sliver of the spotlight of their male counterparts, but some of those women who chose to follow their own paths still found their place in Art History and in the history of promoting gender equality.

The works of Mary Cassatt and Georgia O'Keeffe remain some of the most recognized works from female artists. Is this because they didn't color outside the lines of what was expected of them when they created their art?

Other much lesser known artists like Artemisia painted a woman's struggle in a society dominated by men's forceful nature, and also examined the importance of solidarity between women.

And then there's the famed Frida Kahlo, one of the most famous artists in modern Art History, whose works depict the internal pain of a person who refused to create anything but what her mind's eye saw.

These women's fame is often attributed to a man in their life who thrust their career into the spotlight. With some justice, this can be understood, because those men were the movers and shakers of their time, but let us not let those auxiliary influences be the main discussion around these individuals. With no discredit to these men, it is not possible that those men were subjected to the same treatment as these women, nor did they have to overcome the same obstacles to adorn the pages of history and the walls of our galleries that allow us to know their names.

Our current record of Art History is strongly coupled and warped by sexism, oppression, and the effects of being viewed through a patriarchal lens. The obsession of the female figure throughout Art History is welcomed and appreciated through the ages. And to the same degree, we must pay gratitude to the women who created powerful works that illustrate the ever-present plight of women, and whose message of gender equality will continue to gaze upon us as we study our past. Furthermore, we need to incorporate the relevance of the artist or artwork to that particular historical state of gender equality.

American women earned their right to vote less than a hundred years ago, and are now considered a "protected status" (yes, being a woman has to be artificially protected [19] otherwise, [see the past]). Fighting for one's individualism through art and activism is noble, but fighting for all women's right to vote, to bear or not bear children, to be seen first as a person and not a female person, empowers future generations to continue to pound the issue into the ground and into the canvas until their singular demand to be seen as equal is finally met.

A note from the editor: This article is from the research and opinions of the author and not of Masterworks Fine Art Gallery. It has been abridged, and, thus, many notable female artists are not named here but should be. Some of these notable artists include Berthe Morisot, Peggy Guggenheim, Gertrude Stein, Dora Maar, Sonia Delaunay, Käthe Kollwitz, Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Beatrix Potter, Marie-Thérèse Walter, Elizabeth Siddal, Emilie Flöge, Cindy Sherman, Carrie Maeweems, Marina Abramobic, Yoko Ono, Helen Frankenthaler, Joan Brown, Alice Neel, Kiki Smith, Kara Walker, and Joan Mitchell, to name a few.

Further reading:

- Edouard Manet’s Olympia

- Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? by Linda Nochlin

- Gender Bias in the Visual Arts

- The largest march in US history was the Women's March 2017 (second largest was the Women's March 2018)

- International Women's Day is March 8th, and Women's History Month is March

Citations

- Cindy Nemser, Art talk: conversations with 12 women artists, (1975).

- Ben Davis, Why Are There Still So Few Successful Female Artists?, (2015).

- English Oxford Living Dictionaries, (2018).

- Benjamin Binstock, Who Was the Girl With the Pearl Earring?, (2013).

- Art of the Day, Elisabetta Sirani, Portia Wounding Her Thigh, (2015).

- Ana Nocelotl, Art and Women Fall 2017, (2017).

- [deleted]

- Caroline Cubbage, The Journal of the Core Curriculum, p. 136, (2017).

- Emily A. Francisco, Artemisia in the Metro, (2014).

- Author's note: Her birth name was Jehanne and she called herself by that name, and so will this author. Her full name is pronounced like "ju-ahn dark".

- Ruth Butler, Rodin: The Shape of Genius, (1996).

- Khan Academy, Claudel, The Age of Maturity, (circa 2017).

- National Endowment for the Humanities. Mary Cassatt: A Woman of Independent Mind. Accessed March 2018.

- Hunter Drohojowska-Philp, Full Bloom: The Art and Life of Georgia O'Keeffe, (2005).

- Google Arts & Culture, The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago, (1974-1979).

- Kieron Bryan, Pussy Riot activist recreates Russian prison in London, (2017).

- Khan Academy, A Brief History of Women in Art, (circa 2017).

- Nicole Myers. Women Artists in Nineteenth-Century France. (2008).

- U.S. Department of Justice. Federal Protections Against National Origin Discrimination, (2000).

Tags: gender equality art, gender equality paintings