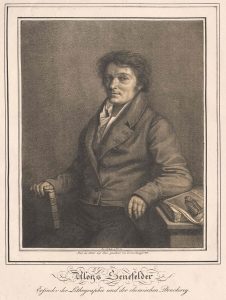

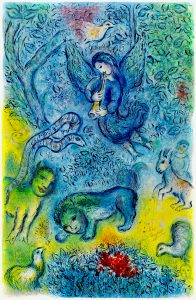

Lithography was discovered in 1798 by Alois Senefelder who sought to find an easier and more quickly way than engraving to print his plays. The medium thrived mostly in Germany in the early 19th century, but suffered popularity from technical difficulties. In 1916, Godefrey Engelmann moved his printing house from Mulhouse to Paris, after which point most of the early kinks were ironed out. This set the stage for France as the center of great lithographic production. It was helped along by the fact that many great French artists took up the trade. Because lithography was an easy means to make many copies of an image, it was often used by portraitists and illustrators. Lithography experienced a revival in the 20th century at the hands of Fernand Mourlot at Atelier Mourlot. Under his direction, some of the masters of the 20th century, such as Marc Chagall, Pablo Picasso,

Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, Joan Miró and others, began working with master printers. The new medium allowed the artists to expand the reach of their work while also challenging them in a new artistic medium. Due to the expediency of the medium, most mass-printed commercial items today, such as magazines are printed using lithography.

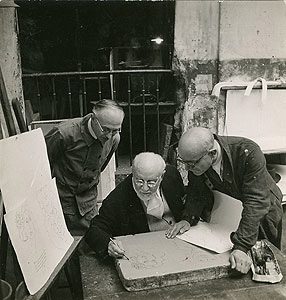

Lithography, coming from the Greek λίθος, meaning rock, and γράφειν, meaning to write, is based on the principal that grease and water are repellent. Originally limestone was the most common stone of choice, due to its porous nature. Zinc and aluminum can also be used. One cannot, however, easily determine the printing surface by looking at the finished lithograph. The obvious downside of using stone it that it is unwieldy and heavy – making it difficult to transport. (Jumping forward in time, this is why Picasso chose linocuts over lithographs when he moved to the south of France.) Most lithographs are a collaborative effort between the artist and the printer. The artist draws the image onto the stone in their method of choice, determining the look of the final image. It is the printer, however, who completes the

complicated lithography process. Due to the difficulty, it is unusual for artists to print their own work – especially in the cases of master artists like Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, and others. These greats, however, would often supervise and always had to approve the final print. This created close and fruitful relationships between many master artists and printers.

The first step of the lithographic process comprises the artist drawing the image onto the stone. This is done in with a greasy marker of some sort, most often crayons (called litho crayons), but can also be done with tusche, a greasy ink. This is essential to lithography, comprising the greasy side of the grease and water repellent relationship. After the image is drawn, the stone is processed. Gum Arabic is applied to the surface, ensuring that the greasy marked areas will remain hydrophobic (water-repellent) and the unmarked surface will be hydrophilic (water-accepting). Nitric Acid can be used to stop the grease from spreading, helping to maintain a sharper image. The printer buffs the stone to reduce the gum to an even layer. After this stage, the stone will sit overnight before the process is repeated again. Lithographic turpentine is sprinkled over the surface to remove most of the greasy material used to draw the original image and leave a slight mark bonded to the stone. After the excess turpentine is wiped clean, the stone is dampened with a cloth. Oily printing ink is applied to the surface, adhering to the to the hydrophobic areas, but being repelled by the blank wet stone.

After the stone is inked, damp paper is applied to the surface to take the print. Damp paper is used because it gathers the maximum amount of details from the print. Then the stone is run through the printer, most often a flat-bed scraper press. Both monochrome and color printing were common. To create a color lithograph, multiple stones (one for each color) had to be used. The lithograph will not reach its full potential until around the 10th print. The final product is a reverse image of the one originally drawn on the stone.

Offset lithograph is another related form of lithography and the one that is most commonly used for commercial printing. In this method, a rubber roller is applied to the stone and picks up the inked image and transfers it to paper. This process allows for the image to be printed in the orientation it was originally drawn. Offset lithography is more easily mechanized and accelerated, making it perfect for commercial printing needs.

Another adaptation to lithograph comes at the beginning of the process, when the artist draws the original image. The artist can choose to use transfer paper. Instead of drawing directly on the stone, the artist can first draw the image on paper covered in a soluble surface layer. Still using a greasy marker, the image is drawn and then placed face down on the stone and made damp until the soluble layer is gone and the drawing adheres to the stone. From here, the remainder of process continues in the same way as detailed above where the artist draws directly onto the stone. The benefit of this is that, similar to offset lithography, the final lithograph is in the same orientation as the first drawing. A downside is that some of the image is almost always lost in the transfer, and the grain of the paper can be noted in the final lithograph.

Lithograph stones leave no plate mark on the final lithograph, a notable difference from other printing methods. Also different, a lithographic stone can produce a number of good impressions, though this does depend on the quality of stone and the choice of methods/materials detailed above. One finished, a lithograph stone can be canceled, meaning it is struck through or written on, ruining the printing potential of the stone. Alternately, the stone can be ground down and reused.

Read more about printmaking techniques.

Sources

Jirousek, Charlotte. “Printmaking Processes.” http://char.txa.cornell.edu/media/print/print.htm

Leicester Print Workshop. “A step-by-step-guide to stone lithography.” http://www.leicesterprintworkshop.com/printmaking/step_by_step_guide_to_stone_lithography/

Griffiths, Anthony. Prints and Printmaking: An Introduction to the History and Techniques. University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, 1996.